- Published: 3 July 2017

- ISBN: 9780143782377

- Imprint: Ebury Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $40.00

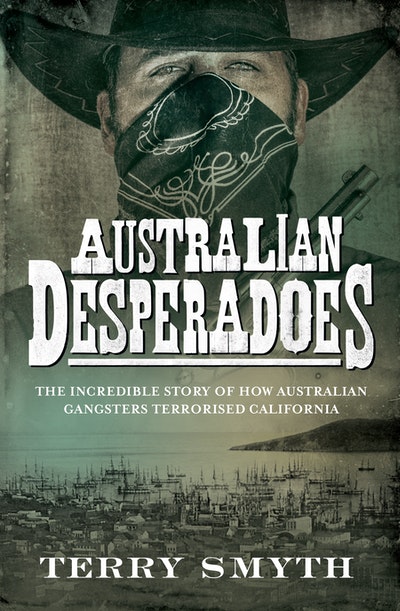

Australian Desperadoes

The Incredible Story of How Australian Gangsters Terrorised California

Extract

The tiny, tattered fishing village of Brighton was fated to change forever when a certain Dr Richard Russell turned his mind to the curious fact that the oceans were so full of salt that salt makers, ‘before they deposit their brine, boil it till it will suspend an egg’.1

From that prosaic observation, Dr Russell deduced:

‘That great body of water, therefore, which we call the sea, and which is rolled with such violence by tempests round the world, passing over all the submarine plants, flsh, salts, minerals, and in short, whatsoever else is found betwixt shore and shore, must probably wash over some parts of the whole, and be impregnated, or saturated with the transpiration, if I may so term it, of all the bodies it passes over: the finest parts of which are perpetually flying off in steams and attempting to escape to the outward air, till they are entangled by the sea and make part of its composition; whilst the salts also are every moment imparting some of their substances to enrich it, and keep it from putrefaction.

‘By these means, this fluid contracts a greater soapiness, or unctuosity, than common water, and by the whole collection of it being pervaded by the sulphureous steams of bodies which pass through it, seems to constitute that ?uid we call sea water, which was intended by the great author of all things to be the common guardian against putrefaction and the corruption of bodies.’2

Russell’s claims that bathing in the sea, and even drinking sea water, were good for the health, popularised in his 1753 book, A Dissertation Concerning the Use of Sea Water in Diseases of the Glands Etc., inspired increasing numbers of England’s upper and middle classes to dip their toes in coastal waters and sample a sip of the briny deep. The good doctor particularly recommended the waters at Brighton, in Sussex, where, by a happy coincidence, he had set up a medical practice in a beachside house – the largest and grandest house in the village. The in?ux of well- heeled visitors – steady for several years – became a stampede after 1783, when George, Prince of Wales, paid a visit to the town, which by then boasted fashionable hotels and rows of houses far grander than Dr Russell’s. The prince – ‘Prinny’ to his entourage of dissolute friends – was a rake, drinker and gambler of no mean repute; as careless with the truth as he was with money and his affections. To announce the prince’s arrival, a gun at the shore battery ?red a salute. Unfortunately, the cannon exploded and killed the gunner, but the death did not dampen the delight at royal patronage, or the ?reworks display that evening.

Prinny stayed in Brighton for 11 days, during which time he rode to hounds, attended a ball and the theatre, and outraged the locals with his carousing. And while there is no mention of him ever going near the water, such was the scramble to go where the royals go and do as the royals do that sea bathing quickly evolved from a mere fad to a kind of mania. With the heir to the throne as its patron, Brighton boomed. The erstwhile ?shing village, now a coastal resort, was the place to go, not just for your health’s sake but for the sake of your social standing.

Picture a boy of 16, identi?able as a local by his smock shirt, and as poor by the state of it, standing on the shingle beach at Brighton, his ears ringing from the splashes, shouts and laughter of tourists wading in the sea, unseen behind their bathing machines. The boy keeps his distance from the machines – a row of covered carts rolled into the water. He knows only too well that the carts, like the people frolicking in the shallows, are from another world.

It is 1834, and the boy is of a generation Brighton’s boom times forgot. He’s too young to remember when the Steine, now covered in rich men’s houses, was covered in ?shing nets from one end to the other, before barriers were erected to keep the ?shermen out. But he is old enough to remember the riots when Sussex farm labourers were thrown out of work by the introduction of agricultural machinery. He knows of the people found dead of starvation on the streets of Brighton, blissfully ignored by the passing parade of toffs on their way to the pavilion, the pier or the beach.

The boy is one of Brighton’s resident poor, who these days almost outnumber the prostitutes and beggars on the streets, pestering wealthy citizens and visitors for a coin or two in the name of Christian charity.

For many, home is one room that serves as bedroom, sitting room and kitchen for up to 30 men, women and children. For those lucky enough to ?nd employment serving the needs of the fashionable resort, cheap housing is available, knocked up in a hurry on the remaining wasteland, with no effective sanitation. In a town famed for its curative waters, few of the streets where the poor live have sewers. Raw sewage is deposited into cesspits carved into the bedrock, which, being porous chalk, cannot prevent the ef?uent oozing through the walls of houses and polluting the drinking water wells. Each year, in the poor streets of Brighton, some 800 people die of contagious diseases.

For the boy on the beach, as for so many Brightonians born to disadvantage, the future is an abstraction hardly worth thinking about. There is only today, and today the chance to climb out of the cesspit involves crime. He clutches in his hand a Bank of England one- pound note. He’s well aware that it’s counterfeit, one of thousands of poor- quality, easily forged notes that have been circulating throughout the country for years. The penalty for forgery used to be death, but had recently been amended to transportation to New South Wales for life. So the boy, deciding that it’s in for a penny, in for a pound, swallows hard and heads for the high street.

The boy’s name is James Stuart.

Australian Desperadoes Terry Smyth

They were the Australians who made American history. In the roaring days of the 1850s California gold rush, San Francisco was the most dangerous town in America, made so by a notorious criminal gang known as the Sydney Coves.

Buy now