Read the story being discussed on Jesse Mulligan’s show on Radio New Zealand on 13 December 2018

A Novel in a Room

by Shonagh Koea

By September of the year Miranda left, he was not sure how he felt. He was wearing the patches by then and had ceased to get the shakes when he thought of cigarettes, when he thought of a lot of things. If he felt like having a drink he just went straight to the telephone and rang the number in his wallet. Then he would go out and sit on the front veranda, waiting for the sound of a car on the gravel road. You could hear a vehicle from a long distance away because the area was so quiet, the silence of the countryside so impenetrable, but it sometimes took a while, maybe an hour or two, before someone came. It was quite a long drive from town and sometimes the one he had been allocated, the one who said to just call him Dave, was not in a position to drop everything for him. He knew that, so he waited.

About the second Wednesday in the month — later he was not sure of the date — he telephoned his sister up north, heard her telephone ring and ring before, breathless, she answered it. She and her second husband ran a fishing charter business and perhaps she had been outside on the jetty, he thought.

‘Come down for the holidays?’ She seemed surprised. ‘But I haven’t even seen the old house for years.’ He heard her words echo his own, like twin recollections of the same past, differently uttered.

‘Perhaps it’s time you did, then.’ His voice sounded somewhat arid, so after he had finished talking to her, this sister he had not seen for eight or nine years, he went and looked at himself in the watery depths of an old pier glass in the hall, seeing himself properly for the first time in months. Before then his attention to himself had been automatic and perfunctory, absolutely minimal, his mind taken up with lawyers, allegations, personal and business letters, many of them from Miranda’s lawyer or Miranda herself. Hers often held the imprint of glasses from which circles of moisture had dripped, or were tear-stained.

The management of the property and all the realities and unrealities of the moment had taken him away from himself. He had not actually looked at his own reflection at all. Thinner, he thought. Greying. One of his knees ached now in damp weather and the index finger of his left hand showed a marked thickening of the upper joint. Arthritis, he supposed. He stood at one of the upstairs windows that evening, looking down at the garden, or what was left of it. Miranda had not been a gardener and he had not had time for flowers. The old tennis court was covered in rank grass now. Sometimes the farm manager put the orphan lambs in there when they were old enough to be weaned, and they would press tame childish faces to the ripped wire and would baa piteously as evening fell.

‘Can’t you get them to be quiet?’ Miranda had asked once.

‘They don’t understand English,’ he had said, and she slapped his face. It was after seven by then and a dangerous time of evening because she would be several drinks ahead and had probably smoked twenty cigarettes since afternoon tea. That was how they had lived.

‘I suppose you thought you loved her,’ the lawyer said that once, at the beginning of all the negotiations.

‘I thought she looked like Marilyn Monroe,’ he said, and wondered if, in his countrified way, he had thought both those ideas were the same. He sat there thinking about it for a while, even though the lawyer was waiting and would charge for the time. ‘She may have thought I looked like someone else as well,’ he said at last. ‘Perhaps someone she once saw at a party. She was a party-girl, Miranda,’ he said. ‘I’m not good at parties. I can’t even dance.’

In the morning, after he had finally seen his greyness and thinness and dreamt about it, he awakened very early and walked across the old lawns and up over the rise at the back of the homestead, through the macrocarpa windbreak that had sighed and groaned in the faintest wind since before he was born. The ground beneath the trees was enduringly dry and littered with a deep mulch of old leaves and twigs. Larger branches, brought down in old storms, still lay there like grasping hands, dry as his own thoughts. He stood there looking at them for a moment or two. Perhaps one of the manager’s boys could cut them up for firewood in the holidays. There would be enough wood for them all, even though it would splatter sparks from the resin. He wrote it down in his notebook. Firewood. Must find fire screen. There must still be one somewhere in that huge house surely?

Down in a slight hollow beyond the big hill was the manager’s house, and he noted again as he approached — he never failed to do this — how well they kept it, how clean the path was, how well the polyanthus were growing in the flower bed beside the big veranda that went around three sides of the place, how the windows glittered in the early morning sun. Marie, his manager’s wife, had come from the town originally but she liked living in the country. Miranda had not. He envied them. He knew they thought him a taciturn man, even churlish sometimes and abrupt, but he often had to turn physically away from their kindness and their happiness and deliberately not see it because he wanted it so much, and it was theirs. He could not have it.

From inside the house he heard a child laughing. There was one much younger than the others, a worldly toddler who had picked up New York slang from adult television programmes at unsuitable hours of the evening and who rode a very small old tricycle with endearing belligerence. Edward remembered being told a story that the bull had run away when the little boy slipped behind his father at an open gate and cycled vigorously into its paddock earlier in the year. The other children were away at school.

Fred had gone already, he was told when he knocked at the back door. Gone out the back of the farm somewhere. Marie waved a hand towards the range of hills to the east. She was wearing rubber gloves to do the breakfast dishes, detergent foam fluttering from them on to the window panes. Said he wouldn’t be back till late afternoon, she said. And she hoped he knew she would have to clean the windows again now, just because of him making her wave. But he saw in her eyes that the admonishment was only a front for a deeper concern, and she had already started to pour him a cup of tea. He imagined, and he knew he could have been wrong, that perhaps they might talk about him gently in the evenings and about what he might be doing in the big house by himself now. And all the mess that had been left. They might talk about all that not unkindly, he thought. And there was the evening Dave was very late and he went to wait for him, nearly gibbering he felt, down by the gate. Their car lights had lit him up when they came home from town or somewhere — he was not sure where they had been and it wasn’t his business anyway. They accelerated up the drive so quickly after stopping to ask how he was that he was sure his assurances of excellence had fooled nobody. From far away, then, he began to hear the sound of another car from town, so he lay down again in the long grass to wait. The moon was rising by then. Perhaps they might talk about that night as well.

The toddler lurked in a corner. He was sitting in a high chair he had almost outgrown and he was eating porridge out of a blue bowl that matched his pyjamas.

‘Hello, Edward,’ the boy said, the clarity remarkable, and Edward suddenly thought that this was the first time, again for months, that he had heard his name uttered as if it may be an ordinary collection of syllables. People had been concerned, respectful, diffident, embarrassed but no one had been ordinary. ‘What do you want?’ The toddler placed a spoonful of porridge in his own mouth and regarded Edward with care.

He wanted a plant — that was it. He wanted to grow a little plant his mother had always had on the sitting-room windowsill. Out the back of the old house the great spaces narrowed down and became a warren of little store rooms, but in the front, looking out towards the hills, the old sitting-room still spread itself out in a commodious kind of way beyond the entrance hall. Miranda had had it differently arranged. In later years it had not been arranged at all.

He wanted a cutting of a plant like that one his mother had had on the windowsill years ago, and Marie and Fred had one exactly the same growing in a little urn on their back porch. So she had snipped a piece off and he came home with it clutched in his hand, had planted it before nightfall in an old terracotta pot from the greenhouse. The toddler, released from the high char, had waved to him as he walked down their garden path, and he turned and waved back rather clumsily. He had not been a waver, not a man who waved.

He sat that evening sometimes looking at the little green sprig as he read the paper. In time it would grow, he knew, into a weeping succulent whose tendrils would trail down the sill, and may sometimes present him with a flower of a pink so startling it would seem improbable. If the toddler had not so boldly asked what he wanted perhaps he may not have had the courage to state a desire for something so simple, because none of them, not Marie nor Fred nor any of them, except the wild toddler, would have divined his excruciating need for a kinder past.

And while he thought of this infinitesimal and comfortable piece of mythology with regard to the house and its windowsills, he also thought he would telephone some cleaning firm or another first thing in the morning and get them to come out from the town, even for two or three days and maybe with a van and, say, two or three people. Perhaps four. He would get the place cleaned up.

The furniture was still beautiful under the dust, and in boxes somewhere was all the porcelain his aunts had bought when they travelled. They had been great ones for old porcelain, his aunts, and he knew it was all somewhere packed away. He remembered an old tea set in a kind of puce colour — unusual — with a pattern of children playing, and suddenly it seemed very desirable that he should see it again and also thus find their silent lost laughter, their joy set in old porcelain.

And there were other things he remembered as well. Tomorrow, he thought, after he had rung the cleaners, he would go and find it all, and when it was assembled and arranged again, it would be like the better elements of his own life placed, like a novel in a room, with exquisite care. In the meantime he took another look at the plant, which appeared to be doing fine so far. He remembered that it came into full flower at Christmas.

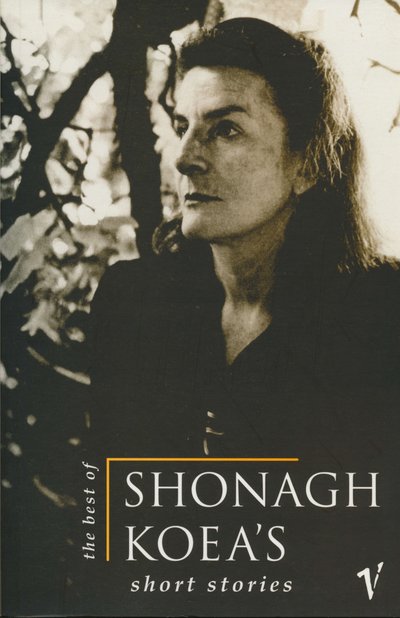

‘A Novel in a Room’ © Shonagh Koea, written for the Hawkes Bay Museum and the Hawke’s Bay Cultrual Trust, and reproduced in The Best of Shonagh Koea’s Short Stories, Vintage 1999.