- Published: 1 June 2021

- ISBN: 9780241986950

- Imprint: Penguin General UK

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 400

- RRP: $30.00

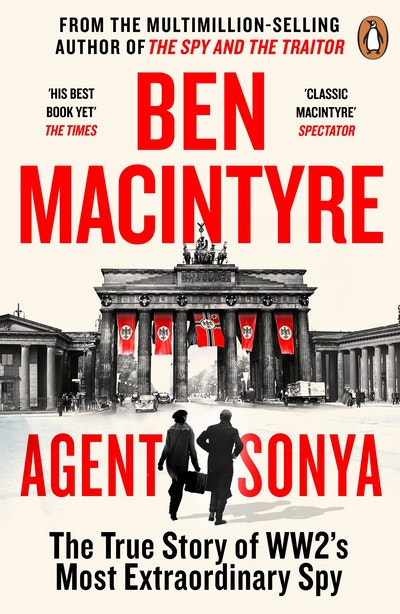

Agent Sonya

Lover, Mother, Soldier, Spy

Extract

They did not know that the woman they called Mrs Burton was really Colonel Ursula Kuczynski of the Red Army, a dedicated communist, a decorated Soviet military-intelligence officer and a highly trained spy who had conducted espionage operations in China, Poland and Switzerland, before coming to Britain on Moscow’s orders. They did not know that her three children each had a different father, nor that Len Burton was also a secret agent. They were unaware that she was a German Jew, a fanatical opponent of Nazism who had spied against the fascists during the Second World War and was now spying on Britain and America in the new Cold War. They did not know that, in the outdoor privy behind The Firs, Mrs Burton (in reality spelt Beurton) had constructed a powerful radio transmitter tuned to Soviet intelligence headquarters in Moscow. The villagers of Great Rollright did not know that in her last mission of the war Mrs Burton had infiltrated communist spies into a top-secret American operation parachuting anti-Nazi agents into the dying Third Reich. These ‘Good Germans’ were supposedly spying for America; in reality, they were working for Colonel Kuczynski of Great Rollright.

But Mrs Burton’s most important undercover job was one that would shape the future of the world: she was helping the Soviet Union to build the atom bomb.

For years, Ursula had run a network of communist spies deep inside Britain’s atomic-weapons research programme, passing on information to Moscow that would eventually enable Soviet scientists to assemble their own nuclear device. She was fully engaged in village life; her scones were the envy of Great Rollright. But in her parallel, hidden life she was responsible, in part, for maintaining the balance of power between East and West and (she believed) preventing nuclear war by stealing the science of atomic weaponry from one side to give to the other. When she hopped onto her bike with her ration book and carrier bags, Mrs Burton was going shopping for lethal secrets.

Ursula Kuczynski Burton was a mother, housewife, novelist, expert radio technician, spymaster, courier, saboteur, bomb-maker, Cold Warrior and secret agent, all at the same time.

Her codename was ‘Sonya’. This is her story.

1

Whirl

On 1 May 1924, a Berlin policeman smashed his rubber truncheon into the back of a sixteen-year-old girl, and helped to forge a revolutionary.

For several hours, thousands of Berliners had been trooping through the city streets in the May Day parade, the annual celebration of the working classes. Their number included many communists, and a large youth delegation. These wore red carnations, carried placards declaring ‘Hands Off Soviet Russia’ and sang communist songs: ‘We are the Blacksmiths of the Red Future / Our Spirit is Strong / We Hammer out the Keys to Happiness.’ The government had banned political demonstrations, and police lined the streets, watching sullenly. A handful of fascist brownshirts gathered on a corner to jeer. Scuffles broke out. A bottle sailed through the air. The communists sang louder.

At the head of the communist youth group marched a slim girl wearing a worker’s cap, two weeks short of her seventeenth birthday. This was Ursula Kuczynski’s first street demonstration, and her eyes shone with excitement as she waved her placard and belted out the anthem: ‘Auf, auf, zum Kampf’, ‘Rise up, rise up for the struggle’. They called her ‘Whirl’, and, as she strode along and sang, Ursula performed a little dance of pure joy.

The parade was turning into Mittelstrasse when the police charged. She remembered a ‘squeal of car brakes that drowned out the singing, screams, police whistles and shouts of protest. Young people were thrown to the ground, and dragged into trucks.’ In the tumult, Ursula was sent sprawling on the pavement. She looked up to find a burly policeman towering over her. There were sweat patches under the arms of his green uniform. The man grinned, raised his truncheon and brought it down with all his force into the small of her back.

Her first sensation was one of fury, followed by the most acute pain she had ever experienced. ‘It hurt so much I couldn’t breathe properly.’ A young communist friend named Gabo Lewin dragged her into a doorway. ‘It’s all right, Whirl,’ he said, as he rubbed her back where the baton had struck. ‘You will get through this.’ Ursula’s group had dispersed. Some were under arrest. But several thousand more marchers were approaching up the wide street. Gabo pulled Ursula to her feet and handed her one of the fallen placards. ‘I continued with the demonstration,’ she later wrote, ‘not knowing yet that it was a decision for life.’

Ursula’s mother was furious when her daughter staggered home that night, her clothes torn, a livid black bruise spreading across her back.

Berta Kuczynski demanded to know what Ursula had been doing, ‘roaming the streets arm in arm with a band of drunken teenagers and yelling at the top of her voice’.

‘We weren’t drunk and we weren’t yelling,’ Ursula retorted.

‘Who are these teenagers?’ Berta demanded. ‘What do you mean by hanging around with these kinds of people?’

‘“These kinds of people” are the local branch of the young communists. I’m a member.’

Berta sent Ursula straight to her father’s study.

‘I respect every person’s right to his or her opinion,’ Robert Kuczynski told his daughter. ‘But a seventeen-year-old girl is not mature enough to commit herself politically. I therefore ask you emphatically to return the membership card and delay your decision a few years.’

Ursula had her answer ready. ‘If seventeen-year-olds are old enough to work and be exploited, then they are also old enough to fight against exploitation . . . and that’s exactly why I have become a communist.’

Robert Kuczynski was a communist sympathizer, and he rather admired his daughter’s spirit, but Ursula was clearly going to be a handful. The Kuczynskis might support the struggle of the working classes, but that did not mean they wanted their daughter mixing with them.

This political radicalism was just a passing fad, Robert told Ursula. ‘In five years you’ll laugh about the whole thing.’

She shot back: ‘In five years I want to be a doubly good communist.’

The Kuczynski family was rich, influential, contented and, like every other Jewish household in Berlin, utterly unaware that within a few years their world would be swept away by war, revolution and systematic genocide. In 1924, Berlin contained 160,000 Jews, roughly a third of Germany’s Jewish population.

Robert René Kuczynski (a name hard to spell but easy to pronounce: ko-chin-ski) was Germany’s most distinguished demographic statistician, a pioneer in using numerical data to frame social policies. His method for calculating population statistics – the ‘Kuczynski rate’ – is still in use today. Robert’s father, a successful banker and president of the Berlin Stock Exchange, bequeathed to his son a passion for books and the money to indulge it. A gentle, fussy scholar, the proud descendant of ‘six generations of intellectuals’, Kuczynski owned the largest private library in Germany.

In 1903, Robert married Berta Gradenwitz, another product of the German-Jewish commercial intelligentsia, the daughter of a property developer. Berta was an artist, clever and indolent. Ursula’s earliest memories of her mother were composed of colours and textures: ‘Everything shimmering brown and gold. The velvet, her hair, her eyes.’ Berta was not a talented painter but no one had told her, and so she happily daubed away, devoted to her husband but delegating the tiresome day-to-day business of childcare to servants. Cosmopolitan and secular, the Kuczynskis considered themselves German first and Jewish a distant second. They often spoke English or French at home.

The Kuczynskis knew everyone who was anyone in Berlin’s leftwing intellectual circles: the Marxist leader Karl Liebknecht, the artists Käthe Kollwitz and Max Liebermann, and Walther Rathenau, the German industrialist and future Foreign Minister. Albert Einstein was one of Robert’s closest friends. On any given evening, a cluster of artists, writers, scientists, politicians and intellectuals, Jew and Gentile alike, gathered around the Kuczynski dining table. Precisely where Robert stood in Germany’s bewildering political kaleidoscope was both debatable and variable. His views ranged from left of centre to far left, but Robert was slightly too elevated a figure, in his own mind, to be tied down by mere party labels. As Rathenau waspishly observed: ‘Kuczynski always forms a one-man party and then situates himself on its left wing.’ For sixteen years he held the post of Director of the Statistical Office in the borough of Berlin-Schöneberg, a light burden that left plenty of time for producing academic papers, writing articles for left-wing newspapers and participating in socially progressive campaigns, notably to improve living conditions in Berlin’s slums (which he may or may not have visited).

Ursula Maria was the second of Robert and Berta’s six children. The first, born three years before her in 1904, was Jürgen, the only boy of the brood. Four sisters would follow Ursula: Brigitte (1910), Barbara (1913), Sabine (1919) and Renate (1923). Brigitte was Ursula’s favourite sister, the closest to her in age and politics. There was never any doubt that the male child stood foremost in rank: Jürgen was precocious, clever, highly opinionated, spoilt rotten and relentlessly patronizing to his younger sisters. He was Ursula’s confidant, and unstated rival. Describing him as ‘the best and cleverest person I know’, she adored and resented Jürgen in equal measure.

In 1913, on the eve of the First World War, the Kuczynskis moved into a large villa on Schlachtensee Lake in the exclusive Berlin suburb of Zehlendorf on the edge of the Grunewald forest. The property, still standing today, was built on land bequeathed by Berta’s father. Its spacious grounds swept down to the water, with an orchard, woodland and a hen coop. An extension was added to accommodate Robert’s library. The Kuczynskis employed a cook, a gardener, two more house servants and, most importantly, a nanny.

Olga Muth, known as Ollo, was more than just a member of the family. She was its bedrock, providing dull, daily stability, strict rules and limitless affection. The daughter of a sailor in the Kaiser’s fleet, Ollo had been orphaned at the age of six and brought up in a Prussian military orphanage, a place of indescribable brutality that left her with a damaged soul, a large heart and a firm sense of discipline. A bustling, energetic, sharp-tongued woman, Ollo was thirty in 1911 when she began work as a nursemaid in the Kuczynski household.

Ollo understood children far better than Berta, and had perfected techniques for reminding her of this: the nanny waged a quiet war against Frau Kuczynski, punctuated by furious rows during which she usually stormed out, always to return. Ursula was Ollo’s favourite. The girl feared the dark, and while the dinner parties were in full swing downstairs, Muth’s gentle lullabies soothed her to sleep. Years later, Ursula came to realize that Ollo’s love was partly motivated by a ‘partisanship with me against mother, in that silent, jealous struggle’.

Ursula was a gawky child, inquisitive and restless in a way her mother found perfectly exhausting, with a shock of dark, wiry hair. ‘Unruly as horsehair,’ Ollo would mutter, brushing ferociously. Hers was an idyllic childhood, swimming in the lake, gathering eggs, playing hide-and-seek among the rowanberry bushes. Part of each summer was spent in Ahrenshoop on the Baltic coast in the holiday home of her Aunt Alice, Robert’s sister.

Ursula was seven when the First World War broke out. ‘Today there are no more differences between us, today we are all Germans who defend the fatherland,’ her school headmaster announced. Robert enlisted in the Prussian Guards, but at thirty-seven was too old for active service and instead spent the war calculating Germany’s nutritional requirements. Like many Jews, Alice’s husband, Georg Dorpalen, fought bravely on the Western Front, returning with a patriotic wound and an Iron Cross. Wealth cushioned the Kuczynskis from the worst of wartime privations, but food was scarce, and Ursula was sent to a camp on the Baltic for malnourished children. Ollo packed a bag of chocolate truffles made from potatoes, cocoa and saccharin, and a pile of books. By the time Ursula returned, an avid reader and several pounds heavier from a diet of dumplings and prunes, the war was over. ‘Take your elbows off the table,’ her mother admonished. ‘Don’t slurp.’ Ursula ran out of the dining room and slammed the door.

Germany’s defeat and humiliation marked the beginning of the end of the Kuczynskis’ halcyon existence. Great cross-currents of political violence swept the country. A wave of civil disturbance triggered the Kaiser’s abdication, and a leftist uprising was brutally suppressed by remnants of the imperial army and the right-wing militias, or Freikorps. On 1 January 1919, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht founded the German Communist Party (the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, or KPD), but were captured and murdered within days. Thus was ushered in the Weimar Republic, an era of cultural efflorescence, hedonism, mass unemployment, economic insecurity and roiling political conflict as the polarized forces of the extreme Right and radical Left clashed with growing fury. Robert Kuczynski’s politics shifted farther left. ‘The Soviet Union is the future,’ he declared after 1922. Though he never joined the KPD, Robert declared the Communist Party to be the ‘least insufferable’ of the available options. In his journalism, he advocated a radical redistribution of German wealth. Right-wing nationalists and anti-Semites took note of Robert’s politics. ‘He is not only against us,’ one German industrialist remarked darkly. ‘He is also extremely impudent.’

The tumultuous fourteen-year period between the fall of the Kaiser and the rise of Hitler is seen as a time of mounting menace, the backdrop to the horror that followed. But to be young and idealistic in those years was intoxicating, edgy and exciting, as the world went mad. War debts, reparations and financial mismanagement triggered hyperinflation. Cash was barely worth the paper it was printed on. Some people starved, while others went on lunatic spending sprees, since there was no point keeping money that would soon be valueless. There were surreal scenes: prices rose so fast that waiters in restaurants climbed on tables to announce the new menu prices every half an hour; a loaf of bread costing 160 marks in 1922 cost 200,000,000 marks by the end of 1923. Ursula wrote: ‘The women are standing at the factory gate waiting to collect their husbands’ pay packets. Every week, they are handed whole bundles of billion-mark notes. With the money in their hands, they run to the shops, because two hours later the margarine might cost twice as much.’ One afternoon, in the park, she found a man lying under a bench, a war veteran with a stump, a pitiful bag of possessions clutched to his breast. He was dead. ‘Why do such awful things happen in the world?’ she wondered.

Agent Sonya Ben Macintyre

The incredible story behind the greatest female spy in history from one of Britain's best historians, now in paperback

Buy now