- Published: 30 January 2024

- ISBN: 9781776950546

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $37.00

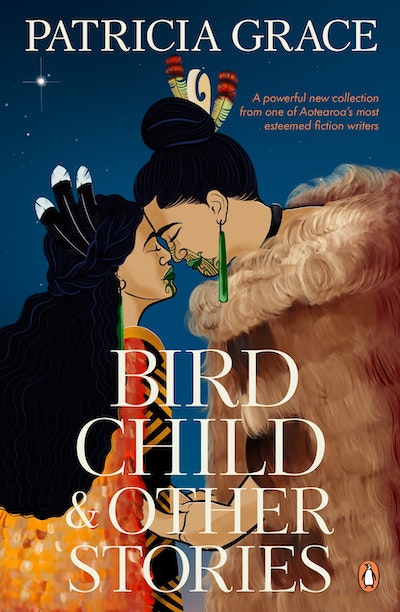

Bird Child and Other Stories

Extract

Nothing I could do once I was in that thoroughfare heading down, nothing at all. Not a thing the watchers could do but wait, hold breath. Not a thing she could do either, despite her attempts to soundlessly seal me, hold me in, my silent, undulating mum. I would have helped if I could, but it wasn’t up to me. This pathway I found myself on was ordained before time started.

One more river to cross, but we won’t be able to do that until nightfall. Also, won’t be able to do it, nightfall or dayfall, if we are dead.

That early morning back in our homeland, as Earth began her roll towards Sun, the women took Mum and me to the women’s spring for the bathing, for the oiling which would keep her skin pliant, and for the mirimiri which would relax her muscles and the bones inside her flesh.

On our way, the women looked across the hillside and saw my great-uncle leaving his sleeping hut, striding with much purpose past the morning fires and into the trees. He is our champion, without peer when it comes to matters to do with war. Where to, alone and in such a hurry? they asked themselves.

The spring is a place sheltered from any wind that blows. It is green and restful and tapu, away from life going on.

As they massaged all parts of my mother, they sang to me about the things they wanted me to know, whakapapa songs telling the genealogies from before the creation of the universe when there was no time. Before time was invented there was Te Kore, which was The Nothing, The Void, The Silence. In that before-time there was nothing to be seen and there were no eyes with which to see, nothing to be heard and no listeners, no fragrances and odours, nor any to know of these. There were no flavours nor any who would taste them. There was no touch and nor were there skin, hair, antennae, filaments or tendrils with which to detect and feel. Nothing sensed. Instead, The Nothing was inhabited by The Potential, wherein resided all that had been laid out for all of time. All there in the dark.Ordained. I couldn’t do anything about that. You can’t argue with immemorial. Nothing to do with me.

How do I know of this? Me, yet to be born? I have learned because my lullabies, the oriori, have been sung to me over and over since the time of my sparking, telling my genealogy from the time, before time, of Te Kore.

Also born into Te Kore was Te Pō, The Night, who was the night of utter darkness, enduring darkness, eminent darkness and every imaginable kind of darkness that could exist. In the womb of Darkness lay Papatūānuku, the Earth, who matured in Darkness and in Darkness became mated with the Sky, who is named Ranginui.

How soothing the recitations as the spark that was me flickered, divided, multiplied, added and subtracted. How balmy, as I lay rocking, kicking, turning, swimming in holy waters, shape-shifting in my pod, listening as the telling continued. From Papatūānuku and Ranginui came all those formidable atua raging and carrying on, followed by the in-betweens/go-betweens who were both worldly and other-worldly. Then came all those tūpuna, then to now . . .

Aren’t you forgetting something? Haven’t you left out several important . . .

Who said that?

. . . from the ancestors to me. Imagine. And there’s more. But at that moment there was nothing I could do to stop myself arriving. As I said, you can’t argue with immemorial.

Back in the homeland, what the early-morning massaging fingers and the stroking hands discovered in that leafy haven was that it was time to make the birthing shelter. According to the fingers and hands, I was stationed, ready for my journey to begin.

The women collected harakeke and kākaho, and began binding and tying to make the shelter for Mum and me. One of the aunties left us and went looking for the scented leavesof the tarata plant to thread here and there through the sides of the shelter. The woman’s search took her back the way we had come, around the hillside and out from the trees that overlooked our dwellings and pātaka. Looking beyond the houses and storehouses, she saw shadows moving, shadows of fighting men, the enemy, running in from three sides in an early-morning raid, catching women cutting harakeke at the swamp, men returning from the eel weirs with the night’s catch, people at the spring filling water containers or out collecting wild vegetables.

Higher on the slope, from the houses, the morning fires, the storehouses, people were alerted, running, gathering what food and water containers they could, snatching children from their sleeping mats, dragging them away from play, wrenching them from the backs of their fathers who were moving quickly to release the boulders which had been set in place in anticipation of such an attack.

The woman scattered her leafy bundle, running back and calling to us.

Women clothed my mother and helped her on to the forest track which would lead us over the hill and down into a ravine. From there we would find the escape path, a hidden passage through dense forest and around large rock formations, which would get us to our pā punanga, a refuge where we could hide until the attack was over, or until we were able to cross the river.

The women left Mum and me to make our own way, with the grandmother to guide us. Some went to assist the men who were levering boulders, preparing, on signal, to roll them onto the enemy, though they knew this was a war we could not win. Our survival depended on the hoariri being halted long enough for an escape into the forest, which is our fortress and all of life to us — our guardian, our sustenance, our true protector. Other women went to accompany the children who were already being led onto a track through the trees.

Mum — with me locked in — and the grandmother made our slow way up through the forest and down into the ravine where the grandmother guided us to where the thin-as-a-throat passage began. All the while my mother was singing to me awaiting song:

Endure, my heart,

Endure,

The time will come

But the time

Is not now.

Over and over, singing into the dark leaves, into the dank soil, into the close, humid air of the forest where we sometimes walked, sometimes climbed, sometimes crawled, until we reached our pāpunanga walled by tall trees and vine tangles at the end of our secreted corridor.

It was some time before we were joined by others — women, children and those with frailties. They had brought what they could of food, water, garments, implements, weaponry and treasured items.

Our arrival had silenced the birds. The only sound came from the spilling river, and close to my heart the whisper of my mother’s abiding song:

Endure, my heart,

Endure,

Endure, the darling of my liver,

The time will come

But the time

Is not now.

Into the green of our hiding-place she sang, into her curved-out belly. ‘It’s all right, Mum,’ I said. ‘I’m fixed, installed. Not going or coming anywhere.’ My mum kept singing:

Go to sleep

My cachet of sweet-smelling leaves

Listen to my song

My adornment of pounamu

Sleep

The time will come

But the time

Is not now.

Sleep is what we did until our fighting men arrived. Dad wasn’t with them. Was he dead? The men rested and drank from the water containers before making their way down to the river to find a suitable place for a crossing. The enemy would not pursue us once we crossed to other territories where we had alliances. Meanwhile, if they came close by, only sound and movement would lead them to this sanctuary of ours.

Dad wasn’t dead. Sometime later he turned up smeared with the blood of the hoariri. With him were two orphans, an infant holding tight round his neck, another running behind. Also following was Maiti, carrying the ancient one on his back so that his sacred feet would not touch the ground. Behind them were a woman and her son whose honoured duty it was to care for the old one, who was now taken down to the river.

The men had found a place, not a safe place but the least unsafe one, where they planned to take us across. It wasn’t a good season, with River at its fastest and fullest, for such an undertaking. Nor was it proper or respectful to River Ancestor to make a challenge at such a time. But this was not intended as a challenge. The crossing was to be attempted only because there was a life-or death reason. It would be successful only if River agreed. The men were relieved to see Ancient One who, with his karakia and his invocations, would plead with River to allow safe passage.

Dad left the riverside and the chanting one, and went scouting, being suited to such an assignment because he is gallant and swift, able to creep, walk or run without feet touching the earth. He can be a shadow or not a shadow. In the landscape he is a feature, a creature, a tree, a bough, and can see through his eyelids. He went alone. Others who may have helped him in this, and who had been caught as they went about their tasks, lay brained and dismembered back in our homeland. But where was our champion of war at this important time, our dreaded one? It was he the hoariri wanted.

My father made his way back the way he had come. Rising smoke told him that the enemy had torched the dwellings and storehouses. Their scouts, he could see, were already out looking for traces of our passing. He created diversions, leaving signs indifferent directions, causing birds to fly. We knew he wouldn’t be seen unless he intended to be seen.

Known as Puna, my father was fetched from a whānau of a River nation to be married to my mother whose whānau is of a Forest nation.

Several generations earlier these two peoples had warred with each other, but the time came when it was judicious to become allied. Conflict had resulted in depletion, loss, death and destruction, with little satisfaction in regard to reprisal. An alliance would mean greater strength against common enemies. Making peace was not a simple matter, as there had been deep grievances between the two.

Conciliation was planned. The people came together with full ceremony. There was exchange, largesse, munificence, honouring; bestowal of fine garments, tools and ornaments; a laying down of weaponry; the provision of food in all of its variety and plenty. There could be no slighting, no withholding if there was to be symmetry.

In that long-ago time there was a marriage of two people of high birth to seal continuing peace between them. From that time on there were many exchanges of food from the forest for kai from the river and ocean. There was sharing of land, and support for each other by fighting men during the war season. Every so often, perhaps once in every second generation, there would be a marriage where the alliance would be re-celebrated and re-confirmed, where the stories would be retold and the genealogies recited many times over.

It was time for another marriage. My to-be father’s people, dressed in their finest and bringing gifts, came to be received by my to-be mother’s people.

As a centrepiece to all on display as the visitors brought him forward, dressed in the way an ariki would be dressed, was the young man known as Puna, who was to be my father — strong,upright, handsome — dressed in a kahukurī, with a high comb and red feathers decorating his top knot of hair. There was nothing my mother’s people could find fault with, nothing they could not admire in his young-man stature, or in the manner in which he was being presented to them.

At the heart of the hosting nation, in costumery suited to a highborn woman, her combed-down hair adorned with three white-tipped feathers and perfumed with karamea, was my to-be mother, Hineataata. Round her neck and in her ears she wore many ornaments of bone and stone. She held herself boldly. With her were her kaumātua, including the very oldest of the grandmothers who hadn’t eaten for several days, also parents, aunts and uncles, all dressed in their finest, an array of hair adornments catching light as their wearers shifted and sighed.

One who was not so elaborately dressed was Hineataata's uncle, Puawhaanganga, the famed war exponent. Though his skin was oiled and his hair piled up high on his head, he was without adornment apart from his facial markings, and without ornament apart from a piece of bone through his ear which had been taken from the corpse of the champion of our long-time enemy — the mutual foe of my soon-to-be mother’s people and my soon-to-be father’s people. There had been a hand-to-hand fight to the death that would never be forgotten by those who bore witness and that had not, so far, been avenged.

The two sat throughout the day as formalities progressed— the rituals of encounter, the speechmaking, the reciting of whakapapa, the chanting of waiata, the gift-giving. They did not look at each other except surreptitiously, until late in the afternoon when the visitors brought my to-be father forward to be handed over to my to-be mother’s people in a giving and receiving ceremony. The celebratory feasting began, with every delicacy being provided, and when darkness came, the couple were taken to the sleeping house which had been prepared for them. They had not yet spoken to each other. It was a night of no moon. In the dark house, the only light was from a small flame burning oil in an indentation in the earth floor. All that was visible of my soon-to-be mother to my soon-to-be father were the white tips of feathers. All she could see of him were two rows of teeth. She giggled behind her hand as though she was shy, and the feathers twitched. But she wasn’t shy. She cupped her hand and reached up under the maro he was wearing to find he had already sprouted. So, they went down, and in a short time the close relationship between the two peoples was reaffirmed.

At some moment during that night — while, away from the sleeping house, feasting continued, stories continued, singing and dancing and celebrating continued; and while close to the sleeping house, grandmothers listened at the walls — I sparked.

Yes.

My newly-become-father’s people stayed on for several days before preparing for the homeward journey. With my father they left the grandson of a woman who had once been a captive. This was Maiti, who had been my father’s close childhood companion, known and admired for his great physical strength and his loyalty. He would be my father’s acolyte, his defender and his confidante.

From the earliest days of my existence, best portions of food were brought to Mum and me. We were caressed and praised. Gifts were being made in preparation for my birth. Songs were sung. Time passed by. The shelter was begun.

When Dad returned, we were told that the enemy, after searching in other directions, was now coming our way, but it’s all right, Dad, the silence and stillness will be the silence and stillness of Te Kore. The waiting song will now be in our two heads only, from my mother to me.

Endure, my heart,

Endure, the darling of my liver,

Sweet-scented pocket of moss and leaves

The time will come

But the time

Is not now.

But oh, oh me, oh Mum, it is now, I know it. The time of my coming is now, is now.

‘Oh me. I know it. The time of my coming is now.’

‘Who? Whose voice is that — nasty, singsong and deriding —fuddling my brain?’

Anyway, something’s happening to Mum and me and there’s nothing I can do to prevent it. Nothing she can do either, there on all fours, two hands gripping a tree root, leaning, biting down on it without disturbance to tree, bird, beetle. No groan, gasp, sigh as she attempts to hold me. She can’t. Nothing she can do to halt the deep dive of me making a way towards the exit. Can’t. It was all decided in Te Kore. Squeezing, silent singing to me, doing her best to seal me. She cannot. The only hands tending her are those of the grandmother, while others wait in the wordless trees, watching or not watching, sleeping or not sleeping, knowing that I could be the death of us. For here I am, on my journey, lamenting:

Where is the shelter for Mum

For me?

Made by mothers and

Scented with tarata leaves

Auē, auē.

‘Auē, Auē.’

‘Who?’

It was not meant to be

In this dank forest

But on the sweet slopes

Of our homeland.

Where are the songs

Of encouragement

Whispers of enchantment

For you, unfurling, Mum,

And for me?

They are far away,

In the place where I was made.

Oh me.

‘Oh me. Oh me. You’re such a tangiweto.’

‘Shut up. Shut up, whoever you may be.’

In the dim light, my silent coiling and uncoiling, Mum implored me, biting down, Wait your hurry.

There’s nothing I can do, Mum, I would if I could, but there’s nothing, here on the threshold. This will be the end of a journey.

Or a beginning.

There were some things I didn’t know, some things not understood as I exited. I didn’t know forest light, forest space, forest smell. It was shocking.

Air.

I didn’t know air. Air assaulted, assailed, magnified. In it poured and should have poured out again. But there was no out-pouring.

Oh no. Out-pouring could not be. I never came to know out-pouring, because . . . Because, the calloused claw-tips of the forefinger and thumb of the grandmother pincered my nose. The bark-hard palm of her hand braced itself over my mouth.

No outflow from me, no scream or cry, no shout or expellation, no sneeze. No tihei mauri ora.

No shout of jubilation from those who witnessed.

No murmur.

No song.

Only

Silent rivers

In the tense, waiting forest.

It’s all right, Mum. Don’t cry. Grandmothers, grandfathers, mothers, don’t weep for me rivers, wetting the sleeping bodies of children. I can be gallant. I can die for my people. Who else is there, at such a young age — only one half of a breath old —who can boast he was the saviour of a nation?

My mother held the emptied flesh of me while the grandmother awaited my pouch, my protector which no longer housed me. It slithered, shapeless, rheumy and pulsing, into her hands. She took a polished stone from around her neck and cut the mooring and sheath away from the body that had been me. Oh me. I held fast to it, my cocoon, wished to creep back inside, wanted it tight about me.

Though they had not yet discovered us, the hoariri were just teeth away, awaiting a sign or sound. There was no sign. There was no sound. Light rain had begun.

As night approached, the hoariri soft-footed away. Fathers arrived in the purple light to fetch the children and take them to the river crossing. They were followed — one step, another step, another, another — by grandmothers, grandfathers, mothers. Only the spider-hand grandmother refused to follow. She sat alone, holding against her the capsule — my former home, the mother from within my mother — until one of her sons came up from the river and spoke to her. She stood and secured the bag — to which I, the essence of me, clung — about his neck and shoulders, and pointed to an opening high in the tree, the tree under which I was birthed and deathed. The man climbed, feeling his way, one hand, one foot, one hand, one foot, to a place where he could steady himself on branches close by the hollow as the grandmother invoked and implored. He unwrapped the membrane from his shoulders and handed us down into this cavity as the kuia continued to call on the atua.

There followed a fearful commotion, a mighty upheaval in the tree, a flapping, beating and rocking, a terrible screeching, ‘Kaa, Kaa, Kaa, Kaa.’ It was not like any disturbance I’d ever experienced. Not like any sound I’d ever heard. Oh me.

‘Dumped on by that narrow mother, that shrivelled kuia and her minion. Muck and ooze, drip flop, right on top . . .’

‘I know that voice.’

‘. . . of my head, my head, you hear. On top of my feathered crown, oozing down. Could’ve choked, could’ve drowned.’

‘Who? Don’t, oh me, don’t kill me, don’t kill me over again.’

‘And all I hear is Oh me. Oh me.’

‘That voice. Inside my head.’

‘You ain’t got no head.’

‘Mocking and scoffing.’

‘You’re not the only one she snuffed, that pinching scrag, that wizened bag. Scourings, on my head, slid down my plumage and smashed my begetting, my precious ones.’

‘Scourings? That’s going too far. That’s overstepping. I’ll have you know . . .’

‘Have you know. Have you know . . .’

Singsong, falsetto. Scraping and combing long claws all down through her feathers.

‘I mean, what do you care? Me, all day hungry. All day thirsty. Didn’t raise a feather to give you away to your hoariri lurking. Think you’re the only ones gallant? Mess. All this mess.’

‘Mess? Language, if you don’t mind, or even if you do mind, I have to say I don’t care for what’s coming out of that mouth of yours.’

‘Beak. Beak. Don’t mouth me. Don’t think I’m one of you lot.’

‘Lot?’

‘You humans. You mouthy ones. Think you know everything.’

‘Beak then. Beak. Don’t like what’s coming out of your beak. What you’re calling a mess, paru, castoff, happens to be . . .’

‘Happens to be, happens to be . . .’

‘My nursery, my wrapper, my mother, my home, where I live.’

‘Lived, you mean. You don’t get it, do you? This thing? It’s haddit, done for. Your old bit of rag is in shreds, can’t you see? It’s cold already.’

It was true. It was true. Cold and dead. No different from the receptacle clutched against my mum, who was now making her way to the river.

That beaky one was shuffling and exploding all about me.

‘My nest and my makings. Haddit, done for, thanks to you. No good anymore.’

She was clawing her way up inside the tree bole, perching on the edge of the hole where the man, urged and guided by the grandmother, had let down the pulsing whenua with its adhering essence, which was me.

Now that sac was empty. The corpse which it had encapsuled had been carried away. Everyone had gone to save themselves. Dad was alive or dead somewhere in the forest.

‘What about me?’ I asked.

That screechy Kaa bird stretched.

‘What about you? You should’ve gone with them while you had the chance, instead of staying here hanging onto that nasty bit of left-over rubbish.’

She perched on the edge of the hole and began cleaning and scraping with beak and claw, down her long back and tail, over and under her wings, her throat, chest and belly, shaking her head, snorting and sneezing. Ha, but when she stretched out her wings I took an opportunity, winkled in under one of those wingpits where it was musty, comfortable and on fire because of underwings being flame red — a suitable place, I thought, for the flicker that I was.

‘Out, Out.’

But I wouldn’t, I stayed, and all her flapping and snapping didn’t make any difference. It couldn’t make any difference, me being in the state of existence I now was, with nothing which could be beaked or clawed.

Bird Child and Other Stories Patricia Grace

A powerful new collection from one of Aotearoa's most esteemed fiction writers.

Buy now