- Published: 16 July 2019

- ISBN: 9781784164126

- Imprint: Black Swan

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $30.00

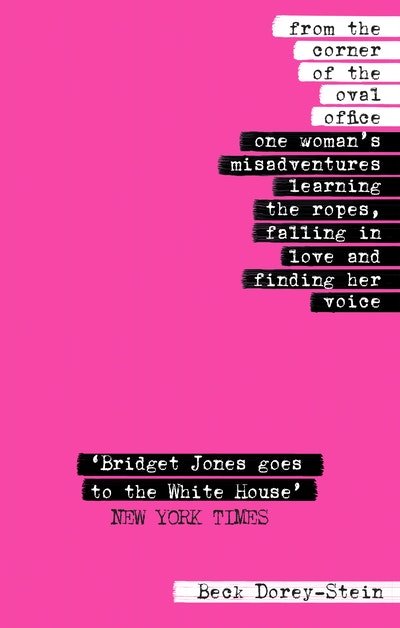

From the Corner of the Oval Office

One woman’s true story of her accidental career in the Obama White House

Extract

Prologue

This place

On a night like this, I wait for the voice of god.

Any minute now, President Obama will deliver remarks in the East Room of the White House. Across one parking lot, down three hallways, and up five flights of stairs in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, I lie on the couch in my little office as the setting sun drenches the room in flammable orange. The Voice of God is the anonymous person who announces the president. I wait to hear him.

Any minute now.

I’ve become so good at waiting.

Remember when you were small, those rare nights when you would return to your elementary school after dinner to perform in the holiday concert or the spring play? You’d run ahead of your parents and past your sleeping classroom, toward the sound of kids laughing, teachers shushing. Each step pulsing with kinetic mischief, your heart racing to be in this sacred space at such a magical hour. Round the corner to the big kid hallway and there they are, all your friends, already lined up in their matching black pants and white button-downs, beckoning for you to join them because tonight, anything can happen. You’re in the right place.

Finally, I hear the Voice of God and walk over to the closed-circuit television to turn up the volume. A minute later, the president appears on the screen, cracks jokes, and takes his characteristic pauses before addressing the topic of the evening. He speaks eloquently, evenly, sincerely. Applause drowns him out when the president blesses the audience and the United States of America. I type the transcript, proofread it, and send it to the press office before zipping up my jacket, putting on my backpack, and closing the wooden office door behind me.

It’s past nine as I walk through the empty hallways at the end of the night. The black-and-white marble floor echoes with secrets and electric possibility.

For the past five years, this house was my home. For so long, this was the only place I wanted to be. Not anymore. Ever since November, each day here feels like a funeral. I have the hallway to myself—even the janitors in their blue aprons pushing their heavy cleaning carts are somewhere else. Doors left ajar reveal bare desks, naked walls, empty black frames, piles of paper next to overflowing wastebaskets. Each room diagrams a different stage of an inevitable divorce.

I walk through the slow automated glass doors of the EEOB and into the chilly darkness of another January night. From the top of the Navy steps, I see clusters of people loitering under the streetlamp after their West Wing tour. The only sound is the hollow clank of halyard against flagpole. This place already feels more like a memorial, less like the well-oiled machine I’ve known it to be. A full moon hovers just above the White House like a flag at half-mast.

This is my school. This is my house of worship. This is my everything—and it is disappearing with each passing day.

I walk by his car and drag my finger across the bumper, knowing agents are watching from their idling SUVs. After waving goodbye to the new guard stuck on night duty, I scan my badge, hear the buzz, the click, the groan of the gate, and walk out onto an empty Pennsylvania Avenue.

This place.

This place.

This place could break your heart.

Everyone keeps talking about the end, but I keep going back to the beginning.

Act I

Connecting the Dots

2011 - January 2012

“So what do you do?” is the first question D.C. people ask, and the last question you want to answer if you’re unemployed, which I am. It’s October 2011, and since the summer, I’ve spent nine to five at my kitchen table writing cover letters no one will ever read. I keep setting the bar lower and lower, and I’m no longer hoping for actual interviews, but just generic acknowledgments that my applications have been received so I know that I haven’t actually disappeared from the universe even if my savings and confidence have. I’ve grown to appreciate employers considerate enough to reject me properly with a courtesy email. The halfhearted Google spreadsheet I keep on my desktop shows zero job prospects but tons of student loans, and rent due in four days. And now it’s time to go blow more money I don’t have at a bar full of douchebags.

Dante failed to mention the tenth circle of hell, which is for people pretending to be happy at a happy hour full of young politicos at a lousy bar with sticky floors two blocks from the White House. These are soulless TGI Fridays–type places, except that the cocktails are $17, and every time I walk into one, the soundtrack from Jaws plays in the back of my head.

I know the question is coming; it’s lurking just below the surface like a patient predator: What do you do? What do you do? What do you do?

Happy hours in D.C. are thinly veiled opportunities to network, hook up, or both. I’m not trying to do either, but here I am at Gold Fin because I promised my boyfriend I’d talk to his coworker’s girlfriend about doing research at her think tank. However, now that I’m here, talking to Think-Tank Tracy seems like a waste of everyone’s time. I’m not a good fit for a think tank, or a PR firm, or a nonprofit; I haven’t even received a generic rejection in weeks. I’m slowly figuring out that I’m not a good fit for this city in general, where everyone acts as if they know something you don’t and dresses as if they’re going to a mob boss’s funeral in 1985. Black on black on black. And not cool New York black. Boring, uninspired, ill-fitting Men’s Wearhouse–meets–Ann Taylor Loft black.

So instead of looking for Think-Tank Tracy, I look for the bartender. I try to get drunk right away so I can stop worrying about my bank account and how I’m going to answer the inevitable “What do you do?” question. As the edges of the room begin to blur, the floor feels less sticky, and life seems beautiful and ironic and funny.

As I wait at the bar for another drink, I watch the pantomime of ladder-climbing bobbleheads who eagerly anticipate the moment they can offer up their freshly minted business cards. These twentysomething Thursday night kickballers and Saturday night kegstanders are as interesting as the bleached walls of this bar, and yet they’re so arrogant, I must be the one missing something. After all, they are real people with real jobs earning real paychecks. They are young professionals who don’t go grocery shopping in sweat pants in the middle of a Wednesday afternoon. Staring into the bottom of my drink, I wonder, When did I fall so far behind? When did I become some loser twenty-six-year-old without a job or a life plan, who isn’t even financially responsible enough to do her drinking at home?

I’m two Cape Codders deep and waiting for a third when a guy with a severe side part and a visible desperation to be his father sidles up next to me, introduces himself, and then casually asks, “So what do you do?”

I know that other people in my predicament say, “I’m between things,” or “I’m weighing my options,” but everyone knows what that means and I hate bullshitting. So instead I look this baby-faced Reaganite in the eye and tell him I don’t have a job.

He keeps an urbane smile pasted on his lips, but I can see him recalculating, the wheels turning. He tilts his head, as though he might be able to assess my condition better from a different angle. This is how three-legged dogs must feel, I think.

The funny thing is, nobody cares what you do. They don’t ask because they’re curious about how you spend your day or what you’re interested in. What D.C. creatures really care about is whether you’re important or connected or powerful or wealthy. Those things can help advance a career. But a jobless girl getting buzzed at the bar can’t do anything for anyone.

The Reaganite backpedals away once he gets another beer, doesn’t even bother to offer me a business card, and so I quickly knock back my third drink and leave the bar before Think-Tank Tracy shows up. On my walk home, I text my boyfriend to say I’m done with happy hours. They make me too depressed.

I’d moved to D.C. in the spring of 2011, by myself, for a semester-long tutoring job at Sidwell Friends School. I would live in the nation’s capital for three months, and not a moment longer, because who wants to live in D.C.? I had enough friends to make a three-month stint exciting, but enough self-respect to know that D.C. and I would never really be into each other. D.C. is the girl who never swears and always wears a full face of makeup; the guy who makes a weekend “brunch rezzie” for him and his ten closest bros and thinks tipping 15 percent is totally solid. I moved to the city with two suitcases and my eyes wide open—I’d use D.C. to build my résumé, and D.C. would take all my money for rent and bland $11 sandwiches.

An exclusive Quaker school, Sidwell Friends flaunts quite a roster of notable alumni, from Teddy Roosevelt’s son to Bill Nye the Science Guy to Chelsea Clinton. In such a pressure cooker, where the Friday speaker series includes parents who also happen to be members of Congress, I was not surprised to learn that Sidwell students were unbelievably worried about not being smart enough or good enough at oboe/squash/debate/all of the above to get into college. So in addition to essay structure and thesis statements, I spent a solid portion of my tutoring sessions reassuring sixteen-year-olds that they were plenty smart, definitely going to college, and absolutely prom-date-worthy. In other words, my job in the spring of 2011 was to help those hormonally charged stressballs chill the fuck out.

Sidwell’s grounds were beautiful, and so were the smoking-hot, super-fit male teachers I saw in the hallways. I assumed the school boasted some top-tier experimental outdoor physical education program to have drawn all this masculine brawn. As a single woman with limited time on campus, I didn’t waste a precious moment playing coy. But every time I looked over to say hi to one of these human Ken dolls in a short-sleeved button-down, he’d look back at me with a quick, close-lipped smile, completely uninterested.

Sitting across from one of the square-jawed teachers in the cafeteria one day, I went for it and introduced myself. He gave me a sheepish smile and explained that he was working. “Working on what?” I asked. He didn’t have a stack of papers, a pile of tests, or even a pen in his hand. He sat there with nothing in front of him, but he was working? He said it again and threw his head in the direction of a group of girls sitting at a table diagonally across from us. I was confused, until one of the girls shrieked “Malia!” and the whole table cracked up laughing.

Oh, right. The Obama girls were at Sidwell, as were Joe Biden’s granddaughters. These guys weren’t male models moonlighting as gym teachers; they were Secret Service agents.

I gave up on the agents around the same time I gave up on D.C. in general. The city was too buttoned-up for me, too obsessed with politics. When my job at Sidwell ended in June, I’d pack up and go wherever the next job took me, abandoning my large group of college friends that had migrated to D.C. after graduation.

Not that D.C. was all bad—I’d miss spending time with Sarah, Erin, Charlotte, Emma, and Jade—five of my former lacrosse teammates whose apartments in Foggy Bottom were as close to one another as college dorms. Living in the District with a deep bench of friends had been like being a senior on a small campus all over again. I was dizzy-busy. There was always a rooftop happy hour or birthday party to attend, or jazz in the National Gallery Sculpture Garden on Friday nights, or boozy brunches on Saturdays that started at noon and ended after dark. We would meet up for runs in Rock Creek Park and make our way down to the National Mall, winding our way among the monuments and lamenting how slow we were compared to our mile times during preseason.

“It’s kind of funny,” Sarah said one Saturday in May as we walked arm in arm to a party on Seventeenth Street. JD and Elle, also Wesleyan alums, were throwing the first barbecue of the season. “It’s kind of like D.C. is the new Wes.”

“Only without the papers or stress or freezing lacrosse games in Maine,” Jade said, shuddering at the memory.

“Or boy drama,” Charlotte said. “Or is there boy drama?”

I feel her elbow in my ribs as they all stop to look at me.

“Nope!”

“Really?” Emma asked. “Any luck with the Secret Service agents?”

“Definitely not. But it’s fine, because I’m not dating guys while I’m in D.C.”

“Does that mean you’re dating girls?” Jade asked.

I shake my head. “I’m only here for one more month. I’m not going to waste my time dating Napoleon wannabes.”

Washington is great for a long weekend to see the monuments and the cherry blossoms, but I find the ethos of this one-trick-political-pony town as seductive as Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. Even the cashier at Trader Joe’s asked me what I did for a living as he bagged my groceries with the spatial reasoning of a Tetris champion.

For once, my social life seemed straightforward. I’d friend-zoned the entire District and felt great about it, because the last thing I wanted in the spring of 2011 was to get tied down to a guy in this ego swamp of a city.

Which is why, of course, I did not fall so much as face-plant in love that night at the backyard barbecue.

From the Corner of the Oval Office Beck Dorey-Stein

The compulsively readable, behind-the-scenes memoir that takes readers inside the Obama White House, through the eyes of a young staffer learning the ropes, falling in love and finding her place in the world

Buy now