- Published: 3 May 2022

- ISBN: 9780143778585

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 176

- RRP: $28.00

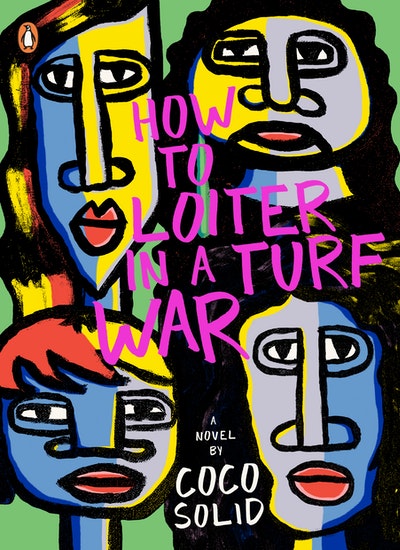

How to Loiter In a Turf War

A Novel

Extract

TE HOIA KNOWS THE CONCRETE WALL has already started to boil under the sun. Her denim ass predictably caramelises as she leans against it anyway. She is inattentive and sick of using both knees.

She touches her earrings. Buses involve a lot of waiting. Squinting. Whenever she touches her jewellery it sounds like a cutlery drawer up close.

At least no one else can hear this jangle.

Or my busted lungs.

Or the random creaks of my body quite like I can.

Why the hell is it so hot today anyway?

Climate change better not fuck up my Matariki.

Te Hoia runs her fingers through the interlocking chains and charms on her wrist.

She remembers a disgusting analogy her friend Rosina once made up.

Riding New Zealand buses, same as riding dick.

You need to be optimistic your next one won’t let you down despite what you know.

You let a bus timetable lie to your face.

But you still get on board don’t you?

I’m just saying. If you and them are going the same way . . . why not hop on?

Te Hoia shudders and smiles; how the straights find the perseverance she’ll never know.

She thinks of Rosina. She thinks of her friends.

Their cluster of mongrel islands. Messy with safety and joy.

Rosina is an aspiring art jerk. She’s Hawaiian, Rarotongan, Sāmoan and . . .

Was it Irish?

I can’t remember what her dad is.

I know he beefs with the Queen too.

Wait, yep. Irish. Pretty sure it was Irish.

Rosina is noisy. She reminds Te Hoia of . . .

Five different-sized pots tumbling out of a cupboard.

Q says Rosina exudes the freedom of children who can yell at their parents.

Rosina relishes conflict and the words ‘what’s that supposed to mean?’ should be tattooed on her neck (among the others already there). Rosina pretends she’s not going to drink tonight but she does, usually to great effect. She likes spilling the secrets of her slower-mouthed friends, friends like Te Hoia. Last Wednesday she impulsively lopped her long black mane into a platinum blonde (or maybe it’s more of a mustard) pixie cut, which Te Hoia has been processing and admiring since.

Little shit, she always looks incredible.

That bone structure takes no prisoners.

Rosina is selling some paintings tonight in a yuk part of town that Te Hoia hates. The girls have to go. No flaking allowed.

Dammit. I wonder how Q is getting into town.

Q is a bedroom poet who will probably leave the exhibition early because she gets up at 4am to work at the (best) bakery before the motorway. Q is Tongan-Fijian ‘with a dash of Indian and Solomon’. Her long hair is always swept to one side; this has been dubbed ‘the ramen sweep’. She has a soft voice which is lucky, as Q’s words always prove the most lethal when pushed. Q is short for her now-ancient nickname Qrispy. This was given to her when she started working at the bakery. But an American franchise bearing a similar name had, predictably, opened next door. Where she lives, the deep-fried multinationals were becoming predatory so in protest she’d curtly graduated to the name Q. She even wrote the term ‘food desert’ instead of ‘dessert food’ on the bakery blackboard. She changed it back when someone implied she was a bad speller.

Te Hoia and Q have been friends for a long time, but lately their glances and secrets have felt a little deeper. Te Hoia has a slippery crush on her friend, but she won’t allow herself to think about it too much.

Te Hoia is at university, studying political sciences.

‘With an interest in gentrification law and environmental racism.’

I’ve been rehearsing that.

She attributes this volatile interest to her two older brothers.

Being terrified of her cuteness as a toddler, they decided to radicalise their sister from the age of three. Te Hoia is Māori and Filipina so finding her fire was never a problem. Her brothers just fast-tracked the process.

Te Hoia is now morbidly late for class (again) because of the bus (again). To catch it now is to favour spite over function. But the bus-stop knows how to make Te Hoia irrationally spiteful, so she waits.

A distant car-horn interrupts her blank stare.

Te Hoia knows a large bag at a desolate bus-stop is mandatory. From her underarm phone-booth she decides to pull out headphones and the bunch of chapped, stained essays. Her lovely lecturer Whetu printed them out for her the other day. She is an older Māori gay professor, so Te Hoia is learning how to be the teacher’s pet for once.

The essays are all written by her favourite author, Piopi Ruta-Chris. She inspects the groovy photocopied books.

Look at this analogue shit. Paper.

Love this old font too.

I forget university was free once.

Everyone was having a blast, even the damn typographers.

While looking down at the papers, Te Hoia startles herself. She sees her outfit and realises she looks cuter than usual. A quick and welcome revelation.

See, why does no one drive past me when I look like this?

I look smart.

Why do people only cruise by when I’m bleeding through my skirt or have oily hair or have been crying about my broken brain?

Well, not today.

Gassed up, Te Hoia now stands swannish and posing with her papers. She enjoys her exterior success so much that for a few minutes she forgets she’s actually meant to be reading. Her mind goes off on pinball tangents. Her focus starts to rattle harder than the road-works nearby. A lollipop man looks at her.

That’s right. Behold the outfit bro — yes, she can dress.

Let me stand here till the bus comes.

Feel my tin earrings, hold my little book.

I’m gonna sway in whatever weather today throws at me, throw no tantrum about waiting.

‘Stealth is wealth,’ like my grandma’s motto.

Te Hoia’s nose crinkles for a moment. She’s trying to celebrate looking sexy, not think about her deceased grandma.

God . . . what a weird motto.

Or should that be Gods . . . plural . . .

Whoever yous are, I know you’re all eavesdropping on me!

She looks up, now paranoid. Her internal life and main character complex are wilding out.

I bet Māori and Filipino Gods eavesdrop more than other Gods too.

Why did I get that combo?

They stand around the fountain of youth like it’s a watercooler.

Comparing notes with the Greek Gods about my psychotic thoughts.

Overheating, Te Hoia steps into a spindly shadow of the bus sign. She’s more agitated by her imagination than impressed. Finally, she surrenders to the text in front of her.

Assorted essays by academic, lawyer and poet Piopi Ruta-Chris. Te Hoia chooses the first essay on the pile, ‘Reupholstering Paradise: The Fever Dream of Fish Restaurants’ taken from Paradigms/Parody of Land Value in the South Pacific © 1989.

This writer makes Te Hoia feel like everyone else, a rare feeling. Whenever she is sad she looks up old Piopi Ruta-Chris interviews schooling arrogant British dudes. VHS-scorched archival footage of a leading wāhine is a must when the racist news hurts your feelings. Piopi always wore a tiny flower in her hair and passed away too young, probably from doing the psychic labour of eighty white male professors. Piopi’s work tethers Te Hoia to a knowing nod that she never thought she’d find inside an institution.

Te Hoia hasn’t chosen her background music yet, but at least the headphones block out construction noises. She accepts the muffle is as good as it’s going to get. She reads through her grimace.

Settled land will always be appraised for a mutating sense of ‘value’. This value requires selective memory and the decimation of all indigenous ideology in order to operate. Imperial scales and semantics will always move with the distrustful times in the South Pacific. But their agenda to erase and reupholster remains soldered to the stolen ground.

Sanitised, colonised narratives often fixate on tangible, singular disputes — the invasion as an isolated moment, a clean cut of beef to serve in the history books. For who can neatly edit the intestinal syrups of countless murder scenes, the whispering and forgotten back-waters that wash against our collective memory while we sleep?

Te Hoia’s dad said that this suburb was a thriving Māori settlement in the 1800s.

Before it did the whole . . . war colonial bloodbath thing.

She wonders if her bus-stop was once where a violent, historical moment had taken place.

These villas are all ‘mutating in value’.

I guess people have always made a killing round here. One way or another.

Oceania is now navigating a new bulldozing model. With gentrification, or ‘urbanization initiatives’, we can now experience multiple upheavals and cosmetic transformations within one suburb, not just one city. Be it Suva, Honolulu, Auckland or Apia, we are now witnessing the hard-won ‘city’ being broken into an array of homogenised host-bodies. The stage is set for ‘Death of a Salesman’ but trust the impact of these letting agents shall live long after we are gone. Residential rupturing and fiscal satire — so much has happened since our people were pulled into the allure of early ‘trade’.

Tonight I am hungry and I can almost smell the whipping fish nets of old. Be they earnest backpacker or depraved pilgrim, it is seldom a grand ambition that lures a supposed saviour to stay. History quietly dictates it is often a private and banal detail that satiates the colonial assertion that they rightfully belong.

Our needs in the modern age may seem more esoteric, complicated. But they aren’t. The reconnaissance and beloved chicanery of our new-wave bounty hunters are no less primal and specific. The racket is the same, it just has a more attractive typeface. Nice space you have here, sure would be a shame if something legislative were to happen to it.

We noble natives have long understood the sleek shifts of word play that are always moving underfoot. Revitalisation. ‘This area has cleaned up a lot.’

Your neighbourhood is the new target. We are as vulnerable to confiscation today as we always were. Within every dealing and exchange we walk the plank. The can(n)on claps probably still ring in your ancestral ears. Your blood intuitively recalls the ‘value’ of your land even if you have no idea. Our right to identify and express all we are historically wrongfully bereft of eludes us, until the eviction notice helps us remember. Our friends leave. Our favourite people can’t make rent.

And who is to say that the scent of fresh fish on a fire did not enhance the Crown’s fever for what we thought we’d always have. Real estate agents put on pots of coffee before selling a house after all. And Māori cannot smell our own shorelines without the Crown’s permission. This essay is now fish fan fiction, I am still hungry.

Some friends of mine moved into a neighbourhood just to be closer to the earthy smells of a legendary restaurant. We still speak of how good our last meal tasted before the restaurant’s rent started to mysteriously levitate. I often wonder, is that meal the restaurant’s true legacy? That spicy oily plate haunts me betterthan any Victorian child. Where do I go for a decent fish curry now?

Te Hoia’s gut fauna assemble into an angry fist. The essays sag in her fingers. This was written in 1989 and yet today here she lurks, looking at the tomb of Salties (the closed fish ’n’ chip shop from her childhood). Currently morphing into . . .

A dog groomer and . . . jeweller!?

A throttling drill noise nearby pops her in the ear. The sound of machinery is now deafening. A bad day at the bus-stop can sometimes feel like a symphony of bullshit.

I’ll tell you where we can get our fish from Piopi.

Nowhere.

Te Hoia lifts her head. All this internal uprising and yet no sign of the bus, only tiny trucks up ahead. She closes one eye and calculates: one faraway truck, if shrunk, could drive perfectly through her bracelet latch. These are the shameful activities she resorts to while waiting.The essay whispers for her to finish reading it.

OK, but gotta be quick.

Y’know. Just in case the bus comes.

Te Hoia gazes up the road one more time, holding the papers over her baked line of vision. Between the bus arriving late and the spluttering asphalt (which she now realises is just are mixed cannon clap) Te Hoia wonders which is going to breakher spirit first.

How to Loiter In a Turf War Coco Solid

A genre-bending work of autobiographical fiction from one of Aotearoa’s fiercest and most versatile artists.

Buy now