- Published: 16 April 2019

- ISBN: 9780241376171

- Imprint: Puffin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 256

- RRP: $27.99

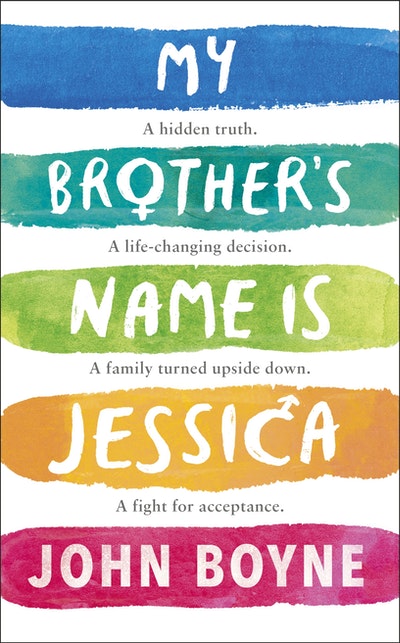

My Brother's Name is Jessica

Extract

‘Nobody needs more than one child,’ insisted Dad. ‘The planet’s overpopulated as it is. Do you know, there’s a family in the street next to ours with seven children under the age of six?’

‘How is that even possible?’ asked my brother Jason, who might have only been a child at the time but knew a little about how the world worked.

‘Two sets of twins,’ replied Dad with a smile.

‘And dogs need constant walking,’ added Mum. ‘And before you say you’d walk him, we all know that you say that now but, in the end, it’ll be your dad or me who ends up doing most of the hard work.’

‘But –’

‘They create an awful mess too,’ said Dad.

‘Which?’ asked my brother Jason. ‘Dogs or siblings?’

‘Both.’

Mum and Dad were so insistent that there would be no further additions to our family that it must have come as something of a shock when they sat him down one day to tell him that he was going to get his wish after all and that, in six months’ time, there would be a new baby in the house. Apparently, he was so excited he ran out into the back garden and charged around in circles for twenty minutes, screaming at the top of his voice, until he got so dizzy that he fell over and hit his head on a garden gnome.

Although that’s not how he got the scar.

When I was born, however, there was a problem. I had a hole in my heart and the doctors didn’t think that I was going to survive for very long. The hole was only the size of a pinhead but, when you’re a baby and your heart is only the size of a peanut, that can be pretty dangerous. I was kept in an incubator for a few days before being brought to an operating theatre, where a team of surgeons tried to repair what was wrong with me. My brother Jason was at home with the au pair at the time, and cried so hard with worry that he fell off the chair and hit his head on a coffee table.

Although that’s not how he got the scar either.

The doctors told my parents that the next week would be critical, but as they’ve both always had very important jobs – Mum’s a Cabinet minister now, although she was just a normal Member of Parliament at the time, and Dad has always been her private secretary – they couldn’t be with me constantly and so took it in turns to come to the hospital. Mum came in during the mornings when the House wasn’t in session, but she was always being called away for meetings, while Dad arrived during the afternoons but didn’t like to stay too long in case there were what he called ‘developments’ that meant he had to get back to Westminster as quickly as he could. But my brother Jason was brought in to meet me for the first time the night following my operation and, even though he was only four at the time, he refused to go home afterwards, and caused so much trouble that eventually the nurses put a cot in the room next to my incubator and let him stay.

‘Baby might sense there’s someone here looking out for him,’ said the nurse. ‘It can’t hurt.’

‘And at least we know he’s safe here,’ said Mum. ‘Plus, we won’t have to pay the au pair double time,’ added Dad.

But then, a few nights later, a noise sounded from one of the machines that were keeping me alive and it gave him such a shock that he stumbled out of his cot in search of a doctor, but, as the room was dark, he tripped over the wire of something called an intravenous infusion pole, and when the nurse came in a few moments later she found me sleeping soundly but my brother Jason lying on the floor in a daze, blood pouring from above his eye where he’d injured himself.

‘Don’t let my brother die!’ he cried out as the nurse examined his wound.

‘Sam’s not going to die,’ said the nurse. ‘Look at him, he’s fine. He’s fast asleep. You, on the other hand, are going to need stitches. Here, hold this towel to your head and let’s go down to my office.’

But my brother Jason was convinced that there was something terribly wrong with me and that, if he left me alone, then something awful would happen. And so he insisted on staying exactly where he was, and eventually the nurse had to sew up his wound right there, and she must have been quite new because she didn’t do a very good job.

And that’s how he got the scar.

I’ve always loved his injury, because whenever I look at it I think of that story and how he insisted on staying by my side when I was sick. It shows me how much my brother Jason has always loved me. Even when he started growing his hair longer, and I didn’t see the scar as often as I used to because he liked to pull his fringe down over his forehead, I knew it was there. And I knew what it meant.

For as long as I can remember, my brother Jason has taken care of me. There were au pairs, of course – lots of au pairs – because Mum said if she didn’t put her constituents first they’d vote for the other side at the next election and then the country would go to rack and ruin. And Dad said it was important that Mum always won by a substantial margin if she was to continue her climb up the greasy pole.

‘It looks good to the party,’ he said, ‘if she doesn’t just win, but wins big.’

Most of the au pairs didn’t stay very long because they said they were professionals with qualifications, they’d been to university, knew their rights and refused to be treated like slave labour. And Mum always pointed out that, if they were so highly educated, then they’d know that slaves didn’t get paid whereas they did, and then she’d turn to Dad and say something like, ‘These are the types that go on marches, protesting against everything, but never actually raise a finger to help,’ and an argument would break out that took in everything from the failings of the health service to nuclear disarmament, by way of the rising price of Tube tickets and the Middle East peace process.

Sometimes my parents and the au pair would reach some sort of agreement, but it only took a few weeks for things to flare up again, and then the original advertisement would be brought out and the girl (and once a boy) would point out that it said nothing about ironing the parents’ clothes, weeding the front garden, or folding thousands of constituency leaflets into envelopes while they were watching television in their own room in their private time. But then Mum would show them the line about ‘other general household duties’ and everyone would start shouting at each other. The phrase If you don’t like it, you can always leave came out, and then Mum and Dad would argue, because he’d say it would take an eternity to find another au pair and he’d be stuck at home with ‘those bloody children’ in the meantime, and Mum would say, Oh, you just don’t want her to go because you like staring at her bum – this is what Mum would say, I’m only telling you – and eventually the au pair would announce that she was going on strike for better conditions, and Mum would say, if that was the case, then she could pack her bags and be gone by the following afternoon and good riddance to bad rubbish.

So they came and went like the seasons and I knew not to waste my time growing too close to any of them. And by the time I was ten my brother Jason was already fourteen, and Mum said we didn’t need an au pair any more – he could bring me home from school every day unless he had football practice, in which case I was to sit in the stands and do my homework until he was finished. And he said fine, but could he get the same money the au pairs had earned, and Dad said, you live in our house rent-free, you eat our food and make a mess with your football boots and your dirty kit, so how about we call it even?

You might think you know some good footballers but, believe me, you don’t know anyone as good as my brother Jason. He started playing football when he was only a toddler, and by the time he was nine years old he’d already had a trial with Arsenal Academy, but they said he wasn’t ready yet and wanted to see him again in a year’s time. Twelve months later he returned for a follow-up, and the coach said that he’d come on in leaps and bounds in the meantime and there was a place for him there if he wanted it, but to everyone’s surprise my brother Jason turned it down. He said that, even though he liked to play at school, he didn’t want it to take over his life, and he definitely didn’t want to become a professional footballer when he grew up.

‘Well, that’s just ridiculous,’ said Mum, who’d had a huge argument with the head of the Academy the year before when they’d rejected him, and made some vague threats regarding sports funding.

‘You’ve obviously got talent. I’ve seen you play and you’re better than every- one else in your class. You always, you know . . . kick the ball and get it into the net . . . Or sometimes you do anyway.’

‘Why not just agree to go for the next seven or eight years?’ suggested Dad. ‘That’s not so long, is it? Just until you finish school, and then you can make a proper decision about your future. It would look very good for Mum if you were signed to a professional football club. The voters would love it.’

‘Because I don’t want to,’ he insisted. ‘I just like playing for fun.’

‘Fun?’ asked Dad, looking at him as if he’d just started speaking a foreign language. ‘You’re ten years old, Jason! Do you really think your life is supposed to be about fun?’

‘I do, actually,’ he said.

‘Do you know what your problem is, Jason?’ asked Mum, who was filing her nails while scanning the newspapers, and he shook his head.

‘No,’ he said. ‘What?’

‘You’re selfish. You only ever think about yourself.’

And, although I was only six years old at the time and sitting quietly in the corner of the room, I also knew that this was completely untrue, because my brother Jason was the least selfish person I knew.

‘Why don’t you want to be a famous footballer?’ I asked him once when I was lying on his bed and he was playing CDs for me and telling me why each song he played was the greatest song ever written and how I needed to broaden my musical knowledge and stop listening to rubbish. As I looked around the room, I saw pictures of footballers on the walls, but then again there was also a poster of Australia and another of Shrek, and I didn’t think he wanted to be a continent or a cartoon ogre either.

‘I just don’t,’ he said with a shrug. ‘Just because I’m good at something, Sam, doesn’t mean I want to spend the rest of my life doing it. There are lots of other things I might want to do instead.’

And, to be honest, that sounded pretty reasonable to me.

Last year, when I was thirteen, my English teacher gave our class an essay to write over the weekend called ‘The Person I Most Admire’. Seven girls wrote about Kate Middleton, five boys wrote about David Beckham and there were three more on Iron Man. After that it was a mixture of people like the Queen, Jacqueline Wilson and Barack Obama. My nemesis, David Fugue, who has bullied me relentlessly since the day I tried to welcome him to our street, wrote about Kim Jong-un, the Supreme Leader of North Korea, and, when our teacher, Mr Lowry, gave him eighty-seven different reasons why Kim Jong-un was not a positive role model, David Fugue waited until he’d finished before saying that he needed to be very careful what he said or he might find himself in serious trouble. He claimed that he played online every night with Kim Jong-un and that they’d become great friends. Just a word from him, he said, and Mr Lowry might find himself on the wrong side of an unpleasant accident when he was walking home one evening. That didn’t go down very well, and David got a letter home to his parents and had to stand up in front of the entire class the next day and apologize for making a casual reference to violence at school.

I was the only person who didn’t write about a famous person. I wrote about my brother Jason.

five things I wrote about in my essay

1. How he’d got the scar on his forehead when I was just a baby, although I lied and said I still had a hole in my heart and could die any day without warning, which isn’t true as the doctors fixed it, but it won me a lot of sympathy anyway.

2. How he’d once saved me from being run over by pushing me out of the way just in time, and when the driver pulled over to tell me off – even though he had clearly been at fault because it was a zebra crossing – my brother Jason chased him back to his car, looking like he was going to kill him if he caught up with him.

3. How he was captain of the football team and could have been a professional footballer if he’d wanted to, but there were lots of other things he wanted to do instead.

4. How he was going out with Penny Wilson, who everyone knew was the best-looking girl in school.

5. How he’d saved me from being eaten alive by Brutus, a horrible dog who lives down the road from us and who always starts slobbering when he sees me, as if he thinks I might be the most delicious treat on the planet.

five things I didn’t write about in my essay

1. How, only a few weeks earlier, he’d had a big argument with Mum and Dad, telling them it was ridiculous that they were never at home, that they always put Mum’s job ahead of us and that he couldn’t be expected to take care of me forever when he had his own life to live. What would happen when he went to university? he asked. But Mum had said that by then I’d be old enough to look after myself, and he’d just thrown his hands in the air and said, I give up, and taken to his room and refused to speak to anyone, even me, for a full day afterwards.

2. How he wasn’t on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or Snapchat because he said he couldn’t stand everyone always going around with their heads in their phones, doing things only so that they could photograph them but never actually experiencing them.

3. How I’d caught him and Penny Wilson kissing in his bedroom the previous week when I ran in without knocking, and he’d chased me out with a tennis racket.

4. How he said that when he was eighteen he was going to vote for the other side and not Mum’s lot, because every one of them was corrupt and they were only in it for themselves.

5. How he’d been growing his blond hair long for a few months now, and putting all these stupid layers in it, even though everyone, including me, thought it made him look a bit girly.

Some of my friends seemed a bit embarrassed for me, writing about my brother like that, but he was the person I most admired, so it seemed only right that he should be the subject of my essay. Whenever I needed him, he was there. When I was a child and had a bad dream, he’d always let me crawl into bed with him and would tell me that everything was all right. When I started to struggle with reading and Dad said they needed to have me tested and it turned out that I had a reading problem, it was my brother Jason who sat down with me every night and helped me with my homework, and, no matter how frustrated I got when the words and the letters started to dance around the page in a way that didn’t make sense, he never ever got impatient with me – he never shouted, Just read what’s on the bloody page! the way Dad did – and he always told me that it would be fine in time, that he’d help me, that he’d always be there for me, that we were brothers, and nothing could ever come between us.

I believed him too.

I knew something was wrong with my brother Jason for about a year and a half before he told us his secret. Although he was still my best friend, he’d started to grow a little more distant towards me – towards all of us – and sometimes he would shut himself in his room and refuse to open the door for hours at a time. I hated when he did that because he’d never excluded me from anything in the past, and it didn’t matter how often I knocked, he’d just shout at me to go away and leave him alone.

Once, when I got home from school, I found him crying on his bed and I didn’t know what to do because it felt like such a reversal of our roles. I was the one who was sometimes sad, especially when I got teased about my reading, and he was always the one who helped to cheer me up. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be there for him too, it was just that I didn’t know how to be a big brother when I’d always been the little brother. It frightened me to see him like that. I asked him what was wrong, and when he sat up I could see from his face that he’d been crying for ages, because his cheeks were red and his eyes were all puffy.

‘Nothing’s wrong,’ he said.

‘Of course it is. You’ve been crying.’

‘Just go to your room, Sam. Please. I don’t want to talk about it.’

And, because I didn’t know what to say or how to help him, that’s what I did.

‘Teenagers,’ Dad said when I asked him about this. ‘That’s the worst of having children, you know. They all turn into teenagers. If they could just go from twelve to twenty overnight, everything would be a lot easier.’

‘But what’s he doing in there?’ I asked.

‘I dread to think. Some things are best left alone, if you ask me.’

‘Don’t you think he seems different in some way?’

‘In what way?’

‘I don’t know. Quieter. Angrier. Upset, a lot of the time.’

‘The only thing that’s different about him, as far as I can see, is that hair of his. I’ve asked him to cut it off, but he refuses. I don’t think he realizes how ridiculous he looks with it hanging down over his shoulders like that. It’s like he thinks it’s the 1970s and he’s the blonde girl out of ABBA.’ He paused for a moment and smiled to himself, as if he was having some sort of weird flashback. Then he sighed and looked all dreamy-eyed.

‘Dad!’ I said, to snap him out of it.

‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘It’s just . . . Agnetha and I had a very special relationship when I was your age. But, honestly, sometimes I feel like just waiting until your brother’s asleep and going in there with a pair of scissors and cutting it myself.’

‘Something’s not right,’ I said. ‘He’s sort of . . .’

‘Sort of what?’ asked Dad, turning to me, and for a moment I thought I could see a look of concern on his face, something I hadn’t seen very often in the past.

‘All I know is that he’s not the same old Jason,’ I said. ‘There’s something on his mind. Something impor- tant. I can tell.’

‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, Sam,’ said Dad, turning back to his computer, where a spreadsheet lay open with the names of everyone from the parliamentary party listed, some with green ticks beside their names, some with red crosses and some with yellow question marks.

‘We’ve all got things on our minds. You should try figuring out who this lot will get behind when the moment comes. I wouldn’t worry about it if I was you.’

‘But I am worried about it!’ I protested.

He stared at me and his eyes held mine for a moment longer than was necessary.

‘You have noticed something, haven’t you?’ I said. ‘No,’ he said.

‘You have!’ I insisted. ‘I can see it on your face.’

‘I haven’t,’ he shouted. ‘Now stop bothering me, all right? I have work to do.’

‘You have,’ I muttered as I walked away.

But nothing concerned me as much as what happened on the day that I came to think of as the Very Strange Afternoon. I’d come home from school earlier than usual – I was supposed to have swimming practice but a seven-year-old had peed in the pool earlier so that was the end of that – and when I put my key in the front door and turned the lock I heard my brother Jason calling out from the kitchen.

‘Who’s that?’ he roared, and something in his tone made me freeze on the spot. I had never heard him sound so anxious before.

‘It’s only me,’ I said, throwing my bag on the floor and making my way down the corridor to see what was in the fridge.

‘Stay where you are!’ he shouted, and I stopped with one foot literally about to make contact with the floor, like a cartoon character.

‘What’s going on?’ I asked.

‘Nothing. Just stay exactly where you are, all right? No, go downstairs to Mum’s office!’

I took a step backwards in confusion and glanced at the door that led to the basement, where I’m not supposed to go. Ever. Mum says that it’s a violation of her sacred space. And that she keeps state secrets down there too. I asked her once whether she had the nuclear codes in her office, and she just laughed and shook her head, saying, Not yet, Sam. Not yet.

‘But I’m hungry,’ I said. ‘I just want a sandwich, that’s all,’ I added, but then he shouted again, and this time I heard such a mixture of anger and terror in his voice that a chill ran through me.

‘Sam,’ he shouted. ‘I’m telling you to go downstairs to Mum’s office right now, do you hear me? You are not to set foot in the living room or the kitchen. Go down- stairs and stay there until I come to get you. Or I’ll never speak to you again. EVER. For the rest of your life. Do you understand?’

I could feel myself growing pale. My brother Jason had never spoken to me like that before, and he’d certainly never threatened to stop speaking to me. I was frightened and confused all at the same time. I wondered whether there were burglars in the house and he was being held at gunpoint and that’s why he didn’t want me to go in. I thought about phoning the police.

‘Please, Sam,’ he said a moment later, his voice quieter now, and I could tell that he was close to tears. ‘Please, just do as I ask. Please. I’ll come downstairs and get you in a few minutes. I promise.’

And so I went downstairs to Mum’s office and sat there, afraid to touch anything in case she found out, and waited for almost twenty minutes before I heard the door open upstairs and my brother Jason’s voice calling to tell me that I could come back up again.

‘Sorry about that,’ he said, unable to look me in the eye, even though I was staring at him in complete confusion because he was acting as if nothing unusual had just taken place. ‘I was finishing some really difficult homework, that’s all, and I didn’t want to be disturbed.’ I said nothing. I knew that he was lying but didn’t want to challenge him. The whole thing had seemed so bizarre. But then I realized what it must have been. He must have had a girl in there, and maybe it wasn’t Penny Wilson but someone else and he didn’t want me to know in case I told someone. Because there seemed to be a faint trace of lipstick on his lips and I could smell perfume in the air.

Mum and Dad were both home the night he told us his secret, which was unusual enough in itself. It was the summer holidays and they were in the living room, Mum reading through some position papers while Dad kept muttering names and saying that he or she was another one they’d have to get on side if Mum was ever to reach what he called the Top Job. I was doing my best to read a Sherlock Holmes story, putting my fingers under the words and using my pencil to separate sentences and phrases just like I’d been shown. I struggled so much with reading because of my dyslexia, but I still wanted books all the time and didn’t care if it took me ages to finish them. I was in the middle of ‘The Man with the Twisted Lip’ when my brother Jason came into the living room and said that he had some- thing he wanted to talk to us about.

‘Can it wait?’ asked Mum. ‘I’m just trying to –’

‘If you need money, get a summer job,’ said Dad. ‘We’re not the Bank of –’

‘It can’t wait and I don’t need money,’ he said, and something in his tone made us all stop what we were doing and turn to look at him. He sat down in the middle of the sofa, as far away from all of us as possible, and started to speak.

‘This isn’t easy,’ he said. ‘What isn’t easy?’ asked Mum. ‘What I’m about to tell you.’

‘Well, spit it out, Jason,’ said Dad. ‘We don’t have all night.’

He swallowed, and I could see that he was trembling a little. He put one hand in the other before him as if to keep himself steady, but his voice still shook when he spoke.

He told us that he’d known something for a long time, something about himself that was very difficult to come to terms with. He told us that he’d always felt it, ever since he was a small child, and that he’d convinced himself it was something he would just have to live with because everyone would hate him if they knew the truth. But recently he’d started to think that perhaps he didn’t have to lie, that maybe he could tell people, be honest with them, and maybe, just maybe, they’d understand.

‘You’re going to say you’re gay, aren’t you?’ asked Mum, putting a hand to her mouth, but my brother Jason shook his head.

‘No, it’s not that,’ he said.

‘Jake Tomlin is gay,’ I said, but no one was listening to me as usual. Jake Tomlin was a boy in my year who’d already told everyone he was gay, but no one was mean to him because he was very strong, and it was obvious that he’d bash anyone who even tried to make a joke about it. I quite liked Jake, but we weren’t too friendly because he was more into sport than me.

‘Can you just hear me out?’ asked my brother Jason.

‘Is that Penny girl pregnant?’ asked Mum.

‘You’re not sick, are you?’ I asked, suddenly fright- ened. ‘You’re not dying?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘It’s nothing like that. I’m fine.’

‘Do you promise?’ I asked.

‘I promise,’ he said. ‘I’m not sick, I’m not gay and Penny’s not pregnant.’

‘Good,’ I said, and I felt myself growing upset at the idea of him having anything wrong with him.

‘Because you’re the best brother in the world, you know that.’

I could hear how sentimental that sounded but I didn’t care. Right at that moment I just needed to say those words out loud and him to hear them.

There was a long silence then while he just stared at the floor, but finally he looked up again and shook his head.

‘But that’s just it, Sam,’ he said. ‘I don’t think I’m your brother at all. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’m not.’

‘Not his brother?’ asked Mum. ‘What on earth are you talking about? Of course you’re his brother. I gave birth to both of you, so I think I would know.’

I stared at him in confusion. ‘What do you mean?’ I asked.

‘Exactly what I say,’ he replied. ‘I don’t think I’m your brother. I think I’m actually your sister.’

My Brother's Name is Jessica John Boyne

A stunning and timely new novel from the bestselling and award-winning author of The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas

Buy now