- Published: 31 March 2020

- ISBN: 9780143774310

- Imprint: RHNZ Adult ebooks

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 352

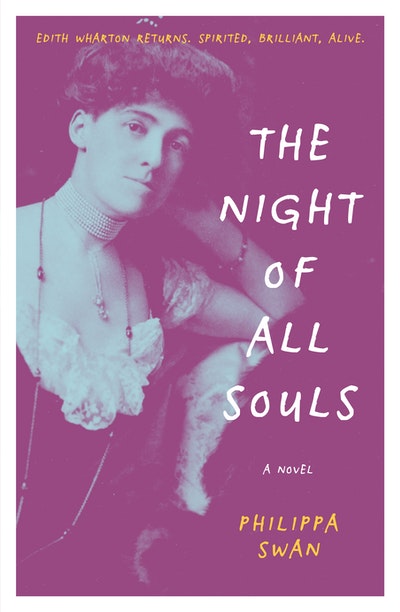

The Night of All Souls

Extract

The letters survive, and everything survives.

Two independent clauses bolted together with a conjunction. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard. A hasty cursive script, but she wasn’t fooled. His careless tone was well crafted. This was a note as calculated as it was casual.

The letters survive, and everything survives.

She’d begged him (countless times) to return her letters, but he always refused. What kind of man did that? Henry James called him incalculable. Yes. He was also a liar. Blackmail and desire. She would do anything for him, risk everything.

The letters survive, and everything survives.

Words that promised such love, underwritten with such vengeance. Words that held the power to destroy everything. Even now.

Chapter I

Drawing herself up from a deep tide of consciousness, Edith opened her eyes.The vague darkness suggested a room, but nothing more. She sat quietly, watching the shadows assume the weight of walls, shapes beginning to form and take substance.

How extraordinary — to be here, to once again be present. She hadn’t been present since . . . well, it must be 1937. The last thing she could remember was the comfort of Elisina’s hand, her warm breath as she explained that Edith had suffered another apoplectic fit and the doctors wanted to perform a bleeding procedure.

Now that ended badly.

So this must be the afterlife — there was no other explanation. Certainly she had written about the afterlife often enough; but she couldn’t recall anything quite like this. It appeared to be a room, small and featureless apart from a broken ceiling light. She could see several incandescent bulbs were missing, wires sprouting from empty sockets.

It was a little unnerving, to be honest, though that had never stopped her before. If she worried about nerves (or honesty) she would not have been a best-selling writer. Nor would she have seen Tunisia.

‘Not sure about this, Edith dear.’

Walter! His chair was pulled up alongside as if they were in a waiting room. She cried with delight, reaching for him; but her body felt oddly cumbersome, weighted like a sandbag. And her out- stretched hand (she saw) was oversized and ugly.

My God, she was old.

Retracting into her chair, tears stung. It was so unjust. She had hoped (and explicitly stated in her memoir) that the afterlife would be a place of re-lived youth; evidently, however, her wishes were to be ignored. Beneath the promontory of her jaw she could feel the swag of her chin. She wasn’t ashamed of old age, but she would prefer young knees. Strangely, the past seemed to have lost its sequence, her later years already as distant as her youth. And her memory was as misty as a ghost story.

Thank goodness Walter was similarly old. She couldn’t bear for him to be young again, with a roving eye. It was always hard work holding his attention; she would have no show now. He was still a handsome man, his white hair swept from a high forehead, a magnificent moustache hiding that small mouth. Forty years they had together. Edith stopped. It was too much; she felt — well, underwhelmed. Was it possible that human emotions in the afterlife were as limited as the furniture? Or was it that Walter’s chair was slightly turned away? He was never one for a scene. More’s the pity.

Until now, her thoughts had been vigorously steered away from the inescapable — those final hours when she had sat by his death- bed. She had been overwrought and weak with exhaustion. She had farewelled Walter with an honesty she hoped would endure for eternity. (Had she known their separation would be of a more interim nature, she might have tempered her tone.) Would he remember any of that? She hoped not.

In the shadowy light, Walter’s moustache tilted as he pondered the pitiful light fitting. The dry familiarity of his transatlantic drawl was almost painful. ‘Must be those ghost stories you took to writing, my dear. Never in the best of taste.’

It was quite true that she had ‘taken’ to writing ghost stories — but only in later years. Until the age of twenty-eight she couldn’t sleep in a room that contained such things. But as to Walter’s observation, she said mildly, ‘You never did approve of my ghost stories, although I don’t recall you complaining when Henry wrote The Turn of the Screw.’

Walter pressed his long fingers together and asked delicately, ‘Have you been here — long?’

A man of such manners and form! Walter knew the etiquette of every situation (he would have done marvellously when the Titanic went down), but he was uneasy in these circumstances. As to his question — had she been waiting long? ‘Not particularly,’ she said, having no idea. Walter had always felt she did nothing but wait for him, all her life. She wouldn’t let him assume she was waiting in the afterlife.

‘Not one of your better ideas, my dear.’

‘I’m not sure it is my idea.’

‘Always interfering with the natural course of things, must be your doing.’

‘You’re probably right.’ Edith was careful to keep a straight face. How could Walter possibly consider this her doing? Walter Van Rensselaer Berry, international lawyer and diplomat, sitting in a lady’s wing chair! She burst with laughter, savouring the sheer physicality of being alive, but Walter coughed pointedly, so she stopped.

Only now did she notice her own chair was shabby and worn, though comfortable enough. It even rocked when . . . no, really? Reaching down, Edith pulled a handle and watched her legs float up. She paused at the sight of bloated feet pushed into carpet slippers. How awful: she had become dingy, like a character in a boardinghouse who collects her dinner from the servery. It was so unfair that women were always judged by their appearance — a fact she never forgot while writing her female characters, and certainly not while making arrangements with her dressmaker. Edith let her legs drop from sight.

It was, however, an excellent chair. She would have enjoyed something like this in her later years, around the time her preference shifted from a French bergère chair to a wicker bath chair with a rubber ring. Yes, this would have done nicely. Rocking gently, she pulled on the lever again, fascinated as her feet mysteriously reappeared.

‘Must you?’ snapped Walter. ‘Always fiddling, and now see what your infernal arranging has done.’

‘My arranging, as you like to call it,’ she said with dignity, ‘was largely restricted to picnics and the occasional sea voyage. I don’t recall making arrangements for the afterlife.’

Walter flinched, twisting a degree further away to murmur, ‘Went a bit Catholic towards the end, didn’t you?’

No, Walter couldn’t know that: he wasn’t there at the end. Should she tell him that they were buried next to each other outside Paris, only ten minutes’ walk from the Palace of Versailles? At least those had been her instructions, and she had every reason to believe Elisina had honoured them. Edith sagged at the memory. Walter’s death had been too much to bear, his useless body . . . no, she wouldn’t recall the end; it mustn’t erase a lifetime — from their youthful escapades as part of the East Coast set to a later life in glorious Europe.

If only she could recapture a single instance together . . . yes, sitting on the terrace at Hyères in their twilight years. It was a summer evening with cabaret music drifting down on the night air from yet another wild party up at the modernist house on the hill. Walter was reading Dante — about a love that moved the sun and stars. Placing the book aside, he’d said with unfamiliar hesitancy, ‘Would you say, Edith — I mean, with us — it’s all been—’ A searching pause and he tried again. ‘It’s all been good, hasn’t it, my dear?’ She was about to reply when a crack of laughter from the party above split the moment like an atom.

Now Edith faced Walter directly, taking comfort from his familiar profile: the small head and hauteur of his movements; the long-jointed frame like a giant insect. She reached out again, forcing her thick fingers to uncurl, but Walter ignored her. Leaning further, she waggled her fingers like a landed fish — still no response. She withdrew. No one could hurt her like Walter. She remembered now the bone-aching aloneness as she stood by his grave, followed by the business of soldiering on. Ten more years she endured, not giving up until her last dog died.

Edith shivered, sensing a cool breeze. She swivelled in her chair but — curiously — there were no doors or windows. The room remained empty except for the arrival of a badly worn rug. It was ludicrous to think she once wrote a best-seller on home decoration. With regard to drawing-rooms (if she remembered correctly) she mentioned the need for imposing proportions and a walnut console.

‘Reckon old Henry will come?’ Walter shifted at last to address her. His pale eyes were the only colour in the room. Now she saw three chairs were scattered about the place. Goodness, she hadn’t envisaged such a possibility — was Henry coming? Directly opposite was an easy-chair (with dirty antimacassars) beside a Hepplewhite with a broken arm. Against the far wall was a spindle-backed oak chair that promised to be hideously uncomfortable. None had the gravitas to suggest an appearance by the great Henry James, which was just as well. Henry would be very surprised — with affectionate malice — to find the irreproachable Mrs Wharton hosting in such surroundings. This was not the sort of show she usually put on.

Clearly they were to be joined by others; but whom? Her life had been long and populous. Long and populous: the words sounded like a threat. Her mind crowded with faces. With panic she shook them away, clearing everyone until she was left with icy absence. Heart racing, Edith breathed deeply, determined to control herself. This was not the time to be overwrought; she must pull herself together and carry on, just as Walter had taught her. She must—

Of course, she remembered now.

At the age of twenty-one, Walter had taught her a brutal lesson about the importance of self-possession and carrying on. Brutal, yes, but it served her well. It was strange to recall that episode — not something she had dwelt on during her lifetime, a lesson that permeated her being like a parable. The original story, however, had become lost as the leading edge of her life sped towards the finish line. Yet now the memories in her overstuffed mind were spilling everywhere.

Yes, but what about those other memories?

Gripping the arms of her chair, Edith forced herself to confront those volatile memories she had so carefully locked away. They were memories she knew must be treated with care, approached with courage and a strength of mind. Were they safely contained — or did they wait in a dark recess of her mind, ready to ambush without warning? The idea was unsettling.

A chime of laughter rang through the room, and Edith watched the darkness pull back to reveal a delicate woman on a plump sofa. Good God, it was Lady Sybil Cutting. The impertinence of the woman was unbelievable. Some things never changed — even now.

Sybil was perched among silk cushions, gold hair shining under the electric light. It was infuriating to admit she was still attractive, but Edith found some solace in the papery skin and shrunken pink mouth. Sybil was a black widow, a woman who entrapped and devoured her mating partners; unfortunately most of them had been Edith’s friends. In desperation, she’d once issued an edict begging that no one marry Sybil for at least a year. Edith tried now to recall the outcome, but her memory was unhelpful.

With a rustle of crushed tissue and a waft of violets, Sybil said, ‘Walter, darling — isn’t this a surprise!’

‘A most delightful one,’ he replied smoothly. ‘You’ve never looked more lovely, my dear.’

Sybil trilled like a caged canary, showing small white teeth.

Edith stiffened. ‘Good evening, Sybil.’

Sybil’s violet eyes opened wide.

Edith gave a suppressed snort of laughter. Many of her unstable characters had been based on Sybil (a particular favourite was Lady Wrench with her outbreaks of hysteria and violent fits of fainting), but Edith didn’t want Sybil here tonight. She had destroyed too many lives. Beauty and carelessness were such a devastating combination.

Tossing her head, Sybil said, ‘I don’t see why you had to arrange something so ghastly.’

‘I believe you’re in the wrong room,’ replied Edith, with some authority. I believe you’re in the wrong room. Her voice sounded ugly and imperious and echoed mockingly from the shadows. Adopting a more reasonable voice, she continued, ‘I believe this is a literary evening —’ was this true? — ‘and you must leave.’