- Published: 2 June 2020

- ISBN: 9781784708092

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $28.00

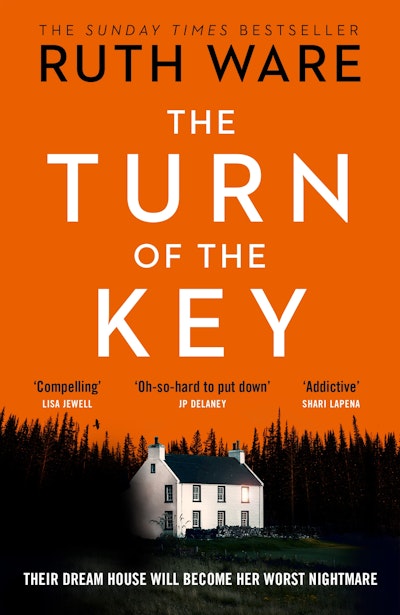

The Turn of the Key

Extract

4 September 2017

HMP Charnworth

Dear Mr Wrexham,

I hope that’s the right way to address you. I have never written to a barrister before.

The first thing I have to say is that I know this is unconventional. I know I should have gone via my solicitor, but he’s

5 September 2017

Dear Mr Wrexham,

Are you a father? An uncle? If so, let me appeal

Dear Mr Wrexham,

Please help me. I didn’t kill anyone.

7 September 2017

HMP Charnworth

Dear Mr Wrexham, You have no idea how many times I’ve started this letter and screwed up the resulting mess, but I’ve realised there is no magic formula here. There is no way I can MAKE you listen to my case. So I’m just going to have to do my best to set things out. However long it takes, however much I mess this up, I’m just going to keep going, and tell the truth.

My name is ... And here I stop, wanting to tear up the page again.

Because if I tell you my name, you will know why I am writing to you. My case has been all over the papers, my name in every headline, my agonised face staring out of every front page – and every single article insinuating my guilt in a way that falls only just short of contempt of court. If I tell you my name, I have a horrible feeling you might write me off as a lost cause, and throw my letter away. I wouldn’t entirely blame you, but please – before you do that, hear me out.

I am a young woman, twenty-seven years old, and as you’ll have seen from the return address above, I am currently at the Scottish women’s prison HMP Charnworth. I’ve never received a letter from anyone in prison, so I don’t know what they look like when they come through the door, but I imagine my current living arrangements were pretty obvious even before you opened the envelope.

What you probably don’t know is that I’m on remand.

And what you cannot know is that I’m innocent.

I know, I know. They all say that. Every single person I’ve met here is innocent – according to them, anyway. But in my case it’s true.

You may have guessed what’s coming next. I’m writing to ask you to represent me as my solicitor advocate at my trial.

I realise that this is unconventional, and not how defendants are supposed to approach advocates. (I accidentally called you a barrister in an earlier draft of this letter – I know nothing about the law, and even less about the Scottish system. Everything I do know I have picked up from the women I’m in prison with, including your name.)

I have a solicitor already – Mr Gates – and from what I understand, he is the person who should be appointing an advocate for the actual trial. But he is also the person who landed me here in the first place. I didn’t choose him – the police picked him for me when I began to get scared and finally had the sense to shut up and refuse to answer questions until they found me a lawyer.

I thought that he would straighten everything out – help me to make my case. But when he arrived – I don’t know, I can’t explain it. He just made everything worse. He didn’t let me speak. Everything I tried to say he was cutting in with ‘my client has no comment at this time’ and it just made me look so much more guilty. I feel like if only I could have explained properly, it would never have got this far. But somehow the facts kept twisting in my mouth, and the police, they made everything sound so bad, so incriminating.

It’s not that Mr Gates hasn’t heard my side of the story, exactly. He has of course – but somehow – oh God, this is so hard to explain in writing. He’s sat down and talked to me but he doesn’t listen. Or if he does, he doesn’t believe me. Every time I try to tell him what happened, starting from the beginning, he cuts in with these questions that muddle me up and my story gets all tangled and I want to scream at him to just shut the fuck up.

And he keeps talking to me about what I said in the transcripts from that awful first night at the police station when they grilled me and grilled me and I said – God, I don’t know what I said. I’m sorry, I’m crying now. I’m sorry – I’m so sorry for the stains on the paper. I hope you can read my writing through the blotches.

What I said, what I said then, there’s no undoing that. I know that. They have all that on tape. And it’s bad – it’s really bad. But it came out wrong, I feel like if only I could be given a chance to get my case across, to someone who would really listen . . . do you see what I’m saying?

Oh God, maybe you don’t. You’ve never been here after all. You’ve never sat across a desk feeling so exhausted you want to drop and so scared you want to vomit, with the police asking and asking and asking until you don’t know what you’re saying any more.

I guess it comes down to this in the end.

I am the nanny in the Elincourt case, Mr Wrexham. And I didn’t kill that child.

I started writing to you last night, Mr Wrexham, and when I woke up this morning and looked at the crumpled pages covered with my pleading scrawl, my first instinct was to rip them up and start again just like I had a dozen times before. I had meant to be so cool, so calm and collected – I had meant to set everything out so clearly and make you see. And instead I ended up crying onto the page in a mess of recrimination.

But then I reread what I’d written and I thought, no. I can’t start again. I just have to keep going.

All this time I have been telling myself that if only someone would let me clear my head and get my side of the story straight, without interrupting, maybe this whole awful mess would get sorted out.

And here I am. This is my chance, right?

140 days they can hold you in Scotland before a trial. Though there’s a woman here who has been waiting almost ten months. Ten months! Do you know how long that is, Mr Wrexham? You probably think you do, but let me tell you. In her case that’s 297 days. She’s missed Christmas with her kids. She’s missed all their birthdays. She’s missed Mother’s Day and Easter and first days at school.

297 days. And they still keep pushing back the date of her trial.

Mr Gates says he doesn’t think mine will take that long because of all the publicity, but I don’t see how he can be sure.

Either way, 100 days, 140 days, 297 days . . . that’s a lot of writing time, Mr Wrexham. A lot of time to think, and remember, and try to work out what really happened. Because there’s so much I don’t understand, but there’s one thing I know. I did not kill that little girl. I didn’t. However hard the police try to twist the facts and trip me up, they can’t change that.

I didn’t kill her. Which means someone else did. And they are out there.

While I am in here, rotting.

I will finish now, because I know I can’t make this letter too long – you’re a busy man, you’ll just stop reading.

But please, you have to believe me. You’re the only person who can help.

Please, come and see me, Mr Wrexham. Let me explain the situation to you, and how I got tangled into this nightmare. If anyone can make the jury understand, it’s you.

I have put your name down for a visitor’s pass – or you can write to me here if you have more questions. It’s not like I’m going anywhere. Ha.

Sorry, I didn’t mean to end on a joke. It’s not a laughing matter, I know that. If I’m convicted, I’m facing –

But no. I can’t think about that. Not right now. I won’t be. I won’t be convicted because I’m innocent. I just have to make everyone understand that. Starting with you.

Please, Mr Wrexham, please say you’ll help. Please write back. I don’t want to be melodramatic about this but I feel like you’re my only hope.

Mr Gates doesn’t believe me, I see it in his eyes.

But I think that you might.

12 September 2017

HMP Charnworth

Dear Mr Wrexham,

It’s been three days since I wrote to you, and I’m not going to lie, I’ve been waiting for a reply with my heart in my mouth. Every day the post comes round and I feel my pulse speed up, with a kind of painful hope, and every day (so far) you’ve let me down.

I’m sorry. That sounds like emotional blackmail. I don’t mean it like that. I get it. You’re a busy man, and it’s only three days since I sent my letter but . . . I guess I half hoped that if the publicity surrounding the case had done nothing else, it would have given me a certain twisted celebrity – made you pick out my letter from among all the others you presumably get from clients and would-be clients and nutters.

Don’t you want to know what happened, Mr Wrexham? I would.

Anyway, it’s three days now (did I mention that already?) and . . . well, I’m beginning to worry. There’s not much to do in here, and there’s a lot of time to think and fret and start to build up catastrophes inside your head.

I’ve spent the last few days and nights doing that. Worrying that you didn’t get the letter. Worrying that the prison authorities didn’t pass it on (can they do that without telling me? I honestly don’t know). Worrying that I didn’t explain right.

It’s the last one that has been keeping me awake. Because if it’s that, then it’s my fault.

I was trying to keep it short and snappy, but now I’m thinking, I shouldn’t have stopped so quickly. I should have put in more of the facts, tried to show you WHY I’m innocent. Because you can’t just take my word for it – I get that.

When I came here the other women – I can be honest with you, Mr Wrexham – they felt like another species. It’s not that I think I’m better than them. But they all seemed . . . they all seemed to fit in here. Even the frightened ones, the self-harmers and the ones who screamed and banged their heads against their cell walls and cried at night, even the girls barely out of school. They looked . . . I don’t know. They looked like they belonged here, with their pale, gaunt faces and their pulled-back hair and their blurred tattoos. They looked . . . well, they looked guilty.

But I was different.

I’m English for a start, of course, which didn’t help. I couldn’t understand them when they got angry and started shouting and all up in my face. I had no idea what half the slang meant. And I was visibly middle class, in a way that I can’t put my finger on, but which might as well have been written across my forehead as far as the other women were concerned.

But the main thing was, I had never been in prison. I don’t think I’d ever even met someone who had, before I came here. There were secret codes I couldn’t decipher, and currents I had no way of navigating. I didn’t understand what was going on when one woman passed something to another in the corridor and all of a sudden the wardens came barrelling out shouting. I didn’t see the fights coming, I didn’t know who was off her meds, or who was coming down from a high and might lash out. I didn’t know the ones to avoid or the ones with permanent PMT. I didn’t know what to wear or what to do, or what would get you spat on or punched by the other inmates, or provoke the wardens to come down hard on you.

I sounded different. I looked different. I felt different.

And then one day I went into the bathroom and I caught a glimpse of a woman walking towards me from the far corner. She had her hair scraped back like all the others, her eyes were like chips of granite, and her face was set, hard and white. My first thought was, oh God, she looks pissed off, I wonder what she’s in for.

My second thought was, maybe I’d better use the other bathroom.

And then I realised.

It was a mirror on the far wall. The woman was me.

It should have been a shock – the realisation that I wasn’t different at all, but just another woman sucked into this soulless system. But in a strange way it helped.

I still don’t fit in completely. I’m still the English girl – and they all know what I’m in for. In prison, they don’t like people who harm children, you probably know that. I’ve told them it’s not true of course – what I’m accused of. But they look at me and I know what they’re thinking – they all say that.

And I know – I know that’s what you’ll be thinking too. That’s what I wanted to say. I understand if you’re sceptical. I didn’t manage to convince the police, after all. I’m here. Without bail. I must be guilty.

But it’s not true.

I have 140 days to convince you. All I have to do is tell the truth, right? I just have to start at the beginning, and set it all out, clearly and calmly, until I get to the end.

And the beginning was the advert.

The Turn of the Key Ruth Ware

Full of spellbinding menace, The Turn of the Key is a gripping modern-day haunted house thriller from international bestseller Ruth Ware.

Buy now