Ted Dawe speaks with us about self-publication, inspiration, vindication, and the writing of Into The River, winner of the 2013 New Zealand Post Children's Book Awards Margaret Mahy Book of the Year.

What motivated you to write and tell stories?

Storytelling has always been a feature of my family interactions. There were stories that were implanted in my head so early they make up my earliest memories. The different members of the family had different styles of storytelling. Impact was important. The control of one’s audience was essential. Finally, and here’s where the finesse came, the creation of a particular effect.

Two of these storytellers were my Uncle Peter and my grandmother, Rewa D’Ath. Peter’s stories were told in the thriller vein. He was nurtured on Bulldog Drummond, so they were peppered with adjectives and adverbs. Everything seemed to involve an element of violence; there were violent actions, violent noises, violent consequences and violent emotions. Things happened at high speed, everything was exaggerated and the dramatic delivery appealed to boy listeners. We were there, right in the story; it was happening to us.

My grandmother’s stories were of the epic variety. They were played out to us during long car journeys to subdue us, and to stifle the constant arguing and fighting between siblings. One of my grandmother’s favourite stories was the plot of a Jack London-style novel called The Silent Places. It was about the frozen North, trappers and hunters, caribou, snow blindness, the Northern Lights, lethal Indians, scalping – everything that was a universe away from our Otaki childhood. The themes were such things as youthful strength versus the experience and stamina of old age. The love that transcends races. Keeping your word. And the axiomatic truth ‘A Mountie always gets his man’.

As we children listened to these stories, we seemed to absorb the craft of storytelling. It has become a feature of our extended family. The well-told story is a treasure and many of the better ones have been passed on intact, through the generations.

Being a very undistinguished scholar, I never made the connection between oral storytelling and writing until well after I had completed school – and, in fact, completed university. My style developed slowly and I hope that both Peter’s and my grandmother’s styles are somehow embedded in my books. I realised after a while that short fiction didn’t work for me, I needed a broader canvas. I needed space to ‘build up a head of steam’.

What authors or works influenced you to follow a career in writing?

As a kid I read all the shrunken versions of the classic novels. These suited a slow reader and, I believe, allowed me to flesh out the characters with my own imagination. I read these books uncritically, for their plots. I don’t think I became aware of the craft of the writer until I was at school and encountered novels like Lord of the Flies, The Pearl, and The Grapes of Wrath. At the age of 18 or 19 I began to read the vogue novels of the period; Hermann Hesse, Kurt Vonnegut, J. P. Donleavy, Richard Brautigan, Tom Wolfe, and Gore Vidal (the Americans were tops in those days). Then at university I discovered the world of literature, in all its glory. Novels, poetry and plays stretching back hundreds of years. Translated work from many nations. Books that teased my imagination and others that completely bamboozled me. I knew at this stage that here was a tribe I would like to join; the tribe of writers.

Why did you choose to self-publish this book? Did you enjoy that process? Would you do it again?

It is one thing to write a novel, it is another to have someone publish it for you. Being published usually means two things: the publisher thinks you are a skilled practitioner; and the publisher believes they can make money out of your work. After I had written Thunder Road, I visited many schools and talked to students who had read this book. The recurring questions were usually about the enigmatic character called Devon Santos. They wanted to know more about him. ‘What happened to Devon before the book started?’ or ‘Why did Devon have these attitudes?’ or ‘Why did he behave the way he did?’

I wrote two other novels – then I felt I was ready to tackle a big novel. A novel that would comprehensively flesh Devon out. Answer all the questions. When I had finished I had a two kilo, 700+ page monster. I tried to get this published but was turned down. The suggested revisions were impossible. I was in despair. Then one day when I was visiting a high school near Auckland, someone suggested I should cut the monster in half and serve up two books. A brainwave! Why hadn’t I thought of that? So I did it. By the time I had polished up, Part One was 500 pages long and was again summarily rejected.

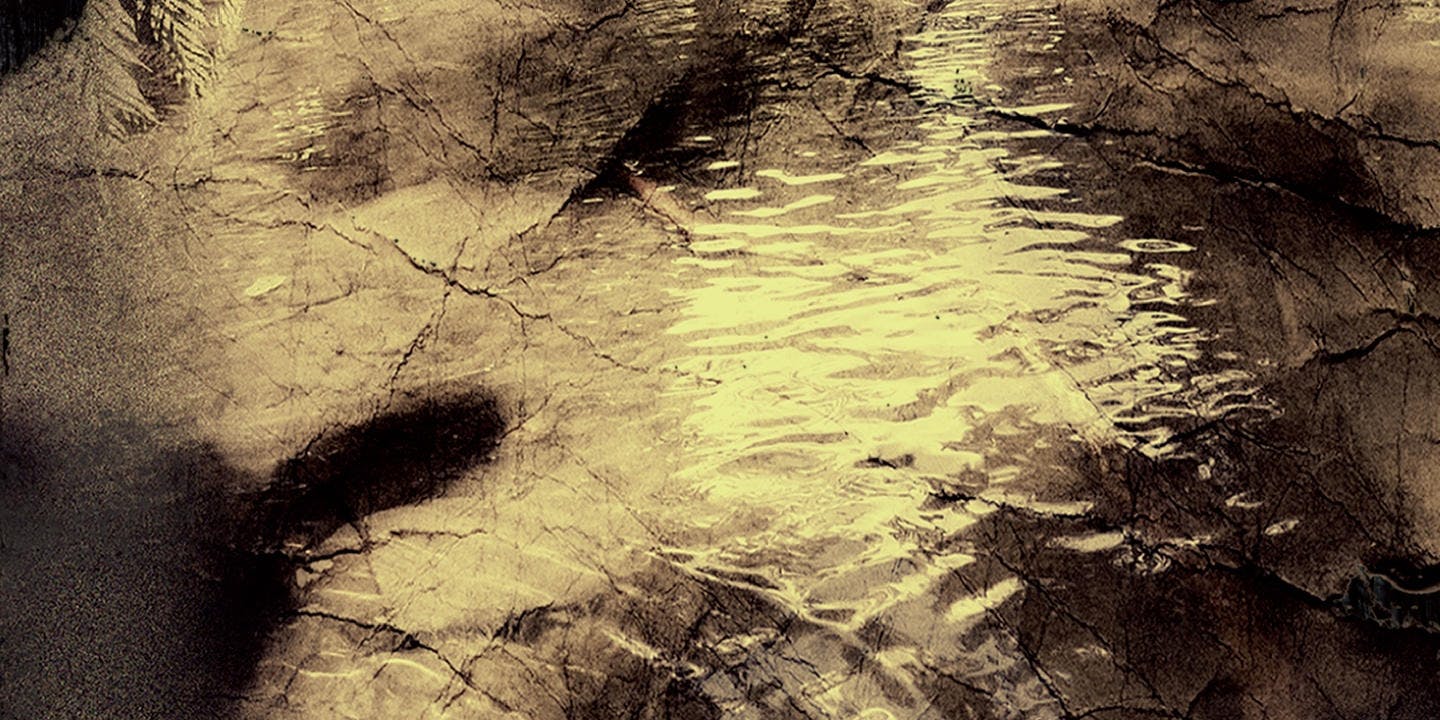

This time I decided to go it alone. I cut the book in half once again, hired a professional editor and a proof reader, enlisted all my literary friends to read it over, and then, just as I was about to resubmit it, decided ‘to hell with it, I’ll publish it myself’. So I did. My wife is an expert photographer and we captured the cover image at a stream in the Waitakere mountains. Several of the students at my school (Taylors College) photoshopped and layered the image to make it look more atmospheric. A printer on the North Shore undertook to run off the book in small runs so I wouldn’t bankrupt the family and stuff the spare room with unsold stock. It was at this point that the hard work really began: marketing. How to get the book known, bought and read. It was here that I really struggled. It was here that the NZ Post Book Awards saved the day and rescued this novel from obscurity. The rest is (as they say) history.

Did I enjoy it? Would I do it again? Answer: a shaky yes. Maybe. I am a determined/stubborn person and it was this character quality/flaw that drove me on. I learned a lot about all the other aspects of the book trade that I knew nothing about. I met many booksellers. I was given tremendous personal feedback which novelists don’t get very often. But it was hard. Risky. And it did take me away from my real job which is to write more novels.

Did your self-publishing efforts create a sense of vindication when you won Margaret Mahy Book of the Year at the NZ Post Children’s Book Awards?

Yes, I felt vindicated. It was an answer to those newspapers which had ignored my book when I sent in review copies. To the publishers who couldn’t see what the book had to offer, or recognise its special qualities. There is something powerful about the idea, that in an arena where there is no hype or persuasion, where three judges work their way through a mountain of books… mine gets selected.

The success of Into the River seems to have sparked an outpouring of support from authors all over the country who are struggling to bring their work to the public eye. However, once the thrill of it died away, I did recognise how incredibly fortunate I was. There is a large measure of personal taste involved in any judgment about a book’s merits. What I did reflect upon (especially when all the controversy blew up about language and content), was that Margaret Mahy herself had readThunder Road. She told me at the LIANZA dinner that she enjoyed it so much that as soon as she had finished it, she read it through again right from the beginning. Kia kaha, Margaret!

Into The River has courted some controversy due to what many consider adult themes. Did you think when writing the book that this controversy would occur and did that reinforce your need to write this story?

Ah, the controversy. In my opinion, the most significant theme is how the individual has to compromise himself (herself) in order to gain acceptance within the group. If you are Maori in a predominantly Pakeha context (like a boy’s boarding school) you have to bury these characteristics in order to survive. Otherwise you will be harassed, humiliated, bullied and belittled. I have seen this many times. The swearing? The sexual acts? The consuming of drugs? To someone like me, who has spent his adult life in classrooms and around teenagers, this is reality. Not pretty, maybe, but undeniable. It is not every teenager, but in my opinion, it is in every school. Teenagers know something about these things. They have opinions about them. They want information and insights. I hope my book helps in this regard. My book doesn’t promote these activities, any more than The Hunger Games promotes ritualistic murder.

Should authors tame their content to match preconceptions or traditions about the intended audience?

If this line of thought was applied to technology we would be living in the stone age. Preconceptions and traditions are about the past. We are striving to understand and make sense of the future. Any artist who strives to break new ground while being chained to the preconceptions and traditions of his intended audience is doomed to fail. Originality, imagination and relevance; these should be the mantra of the artist.

New Zealand has had a long and sad history with youth crime, bullying and sexual exploitation amongst and against our children – and whilst there is no lack of crime tales in NZ fiction, it often doesn’t involve youth specifically. However, your book tackles these topics head-on. Did you feel a need to address these taboos when writing Into The River?

You bet. I have had enough of people pussy-footing around these issues. They are too serious for that. Kids are subjected to hideous abuse in our country and if I can arm them with a little knowledge through my fictions, I will have done something worthwhile. Taboos are all about throwing a blanket over something and hoping it will go away. It won’t. I refuse to stand by passively and pretend it isn’t happening. One of the catch-cries of the politically motivated during the 60s and 70s was ‘Every spectator is a coward or a traitor’. That slogan comes to mind when I think about these issues.

What advice would you share with budding authors in New Zealand?

There are only two requirements for being a writer: the desire to write and having something to say. Everything else can be bought, trained or acquired.

Do you have another book coming?

I never stop writing. I have written a novel about a couple who come to grief in Thailand. It’s called The Day of the Elephants. I am struggling to find a publisher for this because it is said to ‘straddle genres’. I have polished up and submitted the next book in the Devon Santos Trilogy. It’s called Into the World. It takes him from the day he jumps out of the car at the end of Into the River through to the day he walks into Mrs Jacques’ boarding house in Thunder Road. I have just come back from five weeks travelling around France, and I have written a blog about this. I am also working on a ‘self-help’ book called The Story of the Story; a Manifesto of Narrative.