Read the story being discussed on Jesse Mulligan’s show on Radio New Zealand on 19 April 2018

Fear of Cake

For months now you’ve asked yourself, ‘Do I dare?’ You’ve plunged through a maze of research, wrangled plot lines, used soft pencil to draw character arcs on creamy sketch pads of A5. Now the novel’s complete, leaving enough latitude for a reader to imagine what might happen next to the slyly rambunctious heroine, the sooky brother who redeems his sookiness in the penultimate chapter, the gigantic hero with his mysterious knowledge of Anglo-Saxon poetry. Yes, you’re at the end. Write the words in italics and centre them, so—

The End.

But somehow there’s something missing. It could simply be that you don’t want to re-enter the real world just yet. Whatever the reason, you decide to attach a ballad, a sort of echo to the sequence where the heroine meets the castaway sealers.

You reach under the desk and haul out the plastic box that serves as a filing system. As you’re wrenching the lid off, Lolita the cat strolls through the study door.

She sets a paw on the edge of the box and nibbles one of the folders. You shoo her out, and find the folder is labelled Electro-Convulsive Therapy. But inside it are maps and diagrams of an old shopping arcade (Dunedin, 1862). Always and ever, you’re hopeless at filing.

Somewhere in this mess of paper there might be a ballad. Even so, it isn’t likely to fit your particular story, your heroine, your off-centre sense of history.

Could you write one? After all a ballad is only a huge story rendered to a scrap of bone, a twist or two of hair … no, don’t think about that too much or you might feel obliged to ditch the 110,000 word novel you’ve just finished and rework it down to 200 words.

There’s a squeak from your computer. Outlook has reminded you: Lunch. Tomorrow. Cake.

Reality, as they say, bites. It’s your turn to put on lunch for Linda, Eirlys, Elspeth and Jane. Last time you had coffee with Linda, she talked about the awfulness of cakes from the supermarket. No way would you dare to buy a cake.

The female protagonists in your novels, even this one’s sooky brother, and a lover or two here and there, are all good cooks. Writing fiction is a form of wishful thinking.

In the kitchen you set two oranges to boil in a pan. Lolita pads through to watch. You plug in the food processor. The second you start grinding the almonds Lolita streaks out the front door as if you’re firing a machine gun.

You think about ballads. Poetry is not your thing. But a ballad is more like a list, a series of bullet points, key moments in a life. The monumentality of the story is in the gaps, like the vast spaces between mountain peaks.

You break six eggs into a bowl. Usually, your novels are about the gaps in relationships, the gulf that separates husband and wife, lover and lover. Between the moments of high passion lies the mundane. All of us want high passion but how hard it is to capture and to keep. Through the tightest of clasped fingers, it trickles away.

You cut the hot soft oranges into sections and drop them, skin and all, into the mixer. The sealers in the novel are misfits who fill their evenings with tales of fantasy. But they edge away from legends about Selkies, those creatures who are seals upon the sea but on land shed their skins and become beautiful men and women. The Selkie wife, the land-bound man – no matter how great their love, how earnest and deep their intentions – their differences can never be resolved.

The cake goes into the oven. You wipe your hands and set the timer.

Often, the last verse of a ballad repeats the first. Does that mean the story is circular, or that the hapless protagonist (if it’s a ballad the protagonist is usually hapless) starts a similar tragic episode?

You’re back at your desk. Two characters – two voices – a sailor and a Selkie:

A wanderer on the strand, lady, heart heavier than stone

A wanderer wi’ no home nor ship, who’ll never love again

Don’t bid me warm your empty heart, nor beg me bear your child

Don’t bind me here with love, dear sir, the sea is waste an’ wild

Why do you gaze on the sea, lady, wi’ our babes upon your knee

Why do you gaze at the water, lady, when you could gaze on me

A voice calls from the rocks, dear, it moans so fearsome long

It calls me from this hearth, dear, to quiet its sorrowing song

It’s but a seal upon the strand, lady, he’s far away from home

The waves storm-tossed, a creature lost, heart heavier than stone

For seven long year I’ve been your dear, I’ve born you childer two

Don’t follow me down to the strand, my dear, nor bring the bairns wi’ you

Her fair locks drift, the children laugh – oh, search the waves in vain

The sea birds cry, the wind is wild, the ocean’s black wi’ rain

A wanderer on the strand, lady, heart heavier than stone

A wanderer wi’ no home nor ship, who’ll never love again

The bereft sailor on the strand hasn’t a blind clue what he’s done wrong. Love’s like that. Some husbands are like that: not a blind clue. Un-crossable storm-tossed gulfs.

You hope your own life will never be made into a ballad. Your only terror is of having to bake cakes. Yet you write, persistently, about un-crossable mountain divides, lovers on parallel lines who find it so hard to touch and hold on. You have typed The End to a story of the colonial past. You will not think about your real life, your own past, distant enough, thank heaven. Daily life is made up of small tragedies now, small calamities – you hope today’s won’t be the orange and almond cake. Fear of cake is all that happens in a happy ending.

Just as the oven-timer shrills, there’s a thud outside. On the roof? You hurry out. Beneath the shade tree on the patio lies a stunned wood pigeon, silly in its feathery white overalls, like a builder who has toppled off a ladder.

The cat saunters down from the back yard, sees the bird and does a double-take. It’s not as large as she is, but it is fatter.

One wing stirs. The cat crouches. You scream. Her haunches wriggle, you scream again, the wood pigeon flurries onto its belly. You lunge for the cat, she leaps, grabs. With a cartoon whirl of feathers, the bird ends up in the tree.

From the house comes the smell of burning orange. The cat’s pretending the last thirty seconds didn’t happen but a small rain of feathers drifts down.

© Barbara Else, first published in CNZS Bulletin of New Zealand Studies, Issue 1, 2008, Kakapo Books, Centre for New Zealand Studies Birbeck, University of London, re-edited 2018.

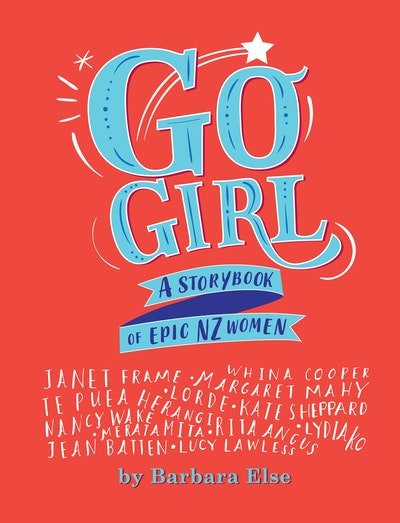

Barbara’s latest publication is Go Girl: A storybook of epic New Zealand women, April 2018.