'We rely on our husbands to choose the politicians for us.’Kate smiled politely and thought 'Rubbish.'

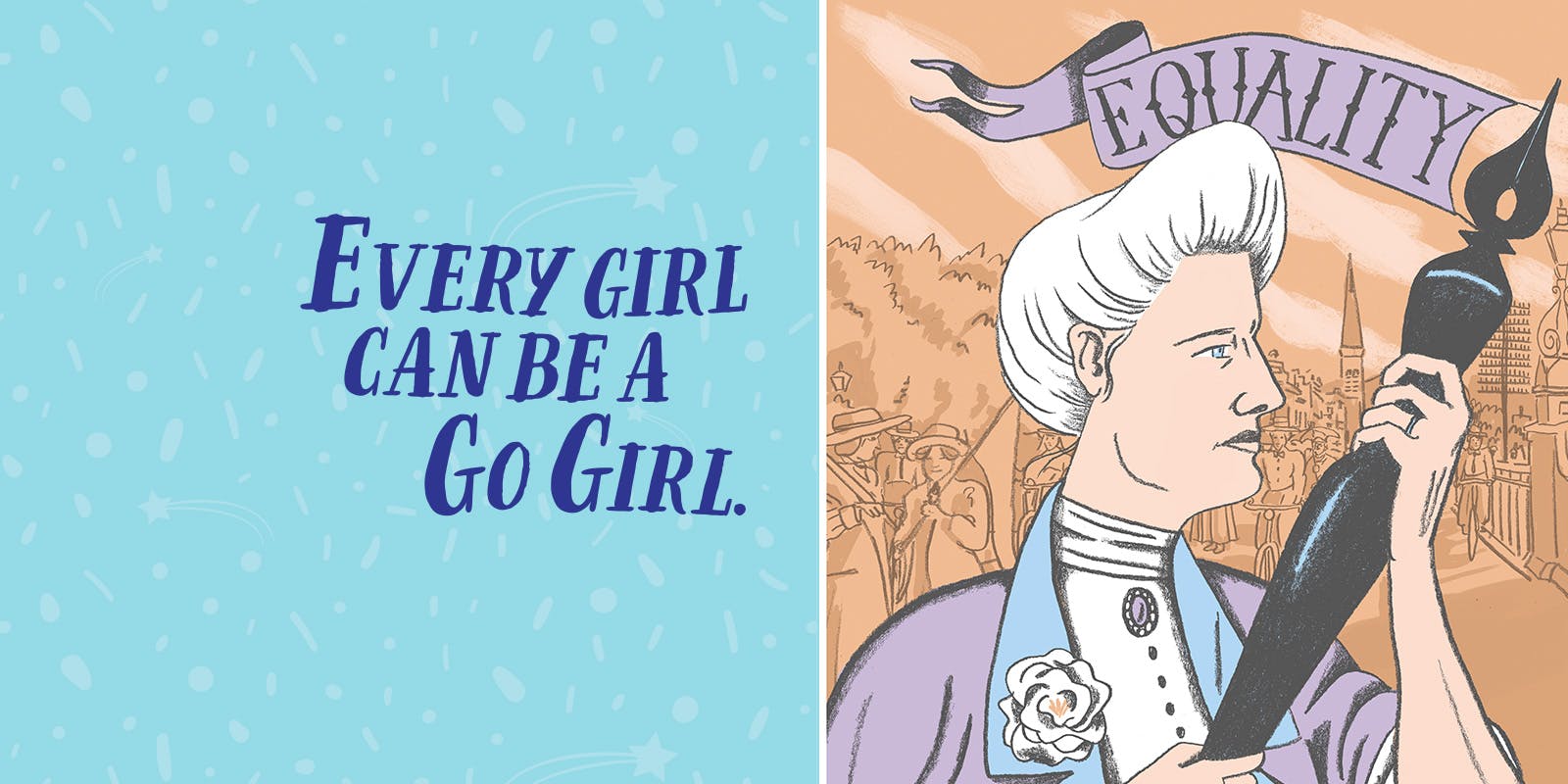

Kate Sheppard | Suffragist

1847–1934 | Born in England; immigrated to New Zealand in 1869

Far away in England lived little Kate. When she was 16, her father died. She had an older sister already living in Christchurch. So her mother brought Kate, another sister and two brothers on the long, dangerous voyage by sailing ship to New Zealand.

Kate had a good education for a woman in those days, and loved to argue for justice. She thought alcohol made men neglect their wives and children, and caused poverty and illness. So she joined the Women’s Christian Temperance Union to campaign against it. Kate was a good and intelligent speaker. She needed to be — the Temperance Union got into dozens of arguments.

People believed women were too fragile to ride bicycles. But Kate joined the first all-women cycling club in Christchurch. ‘Outrageous!’ the stuffy ones cried.

She decided tight corsets and long skirts weren’t sensible, and went riding in knickerbockers, with no corset at all. ‘Shocking!’ the stuffy ones cried even louder.

‘It would be unwomanly for women to vote in elections!’ roared many men. Some women agreed: ‘We rely on our husbands to choose the politicians for us.’

Kate smiled politely and thought Rubbish.

In 1888, with wit and common-sense she wrote: Ten reasons why the women of New Zealand should vote. She organised three petitions about it to Parliament. The first was in 1891. It had no effect. The next was in 1892. Still no effect.

Then in 1893 nearly 32,000 women and men signed a third petition. There were 547 sheets of signatures.

Kate glued all of the pages together. She wound them up around a broom-handle and sent it to Parliament. It was carried into the Debating Chamber and tossed so that it unrolled down the long central aisle — it hit the end wall with a thud.

That very year New Zealand became the first country in the world where all women could vote.

Kate kept arguing to make life better for women and children. During her lifetime, the newspapers often printed letters and articles both for her and against.

But when she died, the Christchurch Times said, ‘A great woman has gone.’

Artwork by Sophie Watson