Read the story being discussed on Jesse Mulligan’s show on Radio New Zealand on 26 July 2018

FreeLOVE

by Sia Figiel

I LISTENED INTENTLY TO Mr Viliamu as the breeze caressed both our faces.

He was a walking encyclopedia who knew just about everything there was to know, and yet he always made whatever knowledge he was passing on seem like it was a gift from God. That he was merely the medium with whom such a gift was exchanged for those of us who needed to receive it.

Momentarily, I felt lucky and special that he stopped to pick me up. To share this knowledge with my ever curious and hungry mind that seemed to absorb everything he said.

A penny for your thoughts, girl, said Mr Viliamu, drawing me back into the conversation.

I didn’t know what he meant.

English, I’m afraid to say, was not my best subject in school, which meant I paid more attention to it than any of the other classes I loved, like Science, Mathematics, Samoan, Social Studies and Health. I kept vocabulary notebooks and studied them and studied them and studied them until I knew meanings of words, but found that there were not too many people in Gu‘usa who spoke it. Perhaps I secretly loved English. Perhaps I didn’t. Perhaps I did and I didn’t. That’s how I felt about English. It was a moody language. At times void of meaning. Empty. Perhaps this feeling of the emptiness of English comes from the blatant fact that I really had no relation to it just as much as it had no relation to me. It wasn’t like my geneaology could be traced through it. Or that the veins in my blood were to be found in its alphabet, the way it is found on my mother’s tattooed thighs. Besides, I did not want to appear fiapoko, like I knew everything, especially before my classmates who struggled with it, as it was a language I too found hard to swallow, that got stuck always in the middle of my throat, especially when I pronounced words like beach, peach, pig, big, and porridge.

And before I could respond, Mr Viliamu asked me again.

Why are you so quiet? What are you thinking about? I’d like to know.

Does he really want to know what I’m thinking about or is he just being polite? Besides, why would the thoughts of a 17-year-old girl be of interest to an old man? He’s at least 10, 12 years older than me! Not to mention the fact that he’s a walking encyclopedia who just happens to be our pastor’s oldest son, which technically makes him my brother!

Nothing, Mr Viliamu, I said, not wanting to disappoint him with my lack of enthusiasm.

I’m not thinking about anything. Besides, it’s what you’re thinking of that I’d like to know. Boldly smiling at him, supposing I had said something that he might find intelligent and would be proud of because it originated from him.

But instead he responded quite differently, as if he hadn’t heard what I had said, which disappointed me, and I showed my disappointment by avoiding eye contact with him and stared instead into the ocean, watching her give birth to waves, listening to them splash onto the lava rocks below the cliffs of Si‘unu‘u, which meant we were halfway to Apia.

Mr Viliamu’s voice echoed suddenly from a far away place, only he was no less than six inches away from me.

You might be embarrassed if I tell you what I’m thinking, he said, rubbing his stomach with one hand as if he hadn’t eaten breakfast as he steered the pick-up truck with his other hand.

What is he saying? Embarrassed? Why would I be embarrassed? Is he going to correct my English? Should I have said a cluster or a crowd instead of a school of birds? They’re birds all the same, aren’t they? But then Mr Viliamu said something else. Something he spoke through the language of his body movements. He started scratching his knee and my eyes followed his hand as it moved from his knee to his inner thigh so that his shorts shrunk upwards and I caught a glimpse of his pubic hair.

Immediately, my eyes darted out the window.

Not only was I embarrassed, frankly, I became offended, not to mention deeply ashamed.

A nervousness entered my body and I thought for a moment that I was going to cry. After all, I had never seen that part of a grown man’s anatomy, and I suddenly found myself thinking about all the males in my family: my uncle Afatasi Fa‘avevesi, who was my mother’s brother and our ‘aiga’s main matai, lived with his wife Stella behind the fale where my mother Alofafua and her sister Aima‘a, Gu‘usa’s traditional healer, and my grandmother Taeao (short for Taeao‘oleaigalulusa) and Ala (short for Alailepuleoletautua), my grand-aunt who was deaf, lived with all the girls of our family and boys under 13, which included my 12-year-old brothers Aukilani (Au) and Ueligitone (Ue), identical twins who loved to play identity tricks on people. The older boys, which included our Uncle Fa‘avevesi’s sons Chris and Emau, as well as our adopted brothers and other taule‘ale‘a or untitled male relatives from either Savai‘i, Manono or Apolima, who were all technically considered my brothers, lived in a house behind Uncle Fa‘avevesi’s house, closer to where the umukuka or kitchen was located.

With all these males around, you’d think I would have seen a full grown man’s penis by now. And yet, the taboos that governed the movements of our brothers in relation to us, their sisters, known as the feagaiga, or the brother/sister covenant, were so strictly observed and highly scrutinised that it meant I’d only witnessed a penis once.

Well, twice actually. But they belonged to my twin brothers Ue and Au, who had been circumcised along with their friends, and were waddling out of the ocean after one of them was stung by a jellyfish.

It was the funniest sight.

Q and Cha and I teased them so badly that their only form of retaliation was in empty threats that further paralysed them by the state of affairs they were caught in.

Imagine the fastest boys of Gu‘usa reduced to waddling turtles, calling out that they’re going to ‘get us’ once their penises were healed. Because that’s going to ever happen, ha! It was utterly hilarious and became a family and village joke recounted over and over by the women at suipi whenever they needed light entertainment to break the monotony of someone’s winning streak.

I clung to the image of my brothers and their friends for safety as I was beginning to feel uneasy with Mr Viliamu.

I didn’t know how I was to ever look into his eyes again with the same confidence he had originally instilled in me at school, now that I had seen something so intimate as his pubic hair.

Perhaps it was an accident, I told myself. He didn’t mean to expose himself to me deliberately. But then again, wasn’t he the very same person who told our class that there were no accidents or coincidences? That every action we make creates a ripple in the universe, which means that all actions are interconnected?

How then could I possibly unsee what I had just seen? Instantaneously, I told myself that this was a bad idea. I never should have accepted Mr Viliamu’s offer in the first place. I would have wholeheartedly given up the six tala my mother had given me for busfare to sit next to an old man who hadn’t showered in a week in a crowded bus with babies crying and old women smoking Samoan tobacco, and Cyndi Lauper’s Time after Time playing over and over and over, not to see what I had just seen.

But it was too late, I suppose.

As my Aunty Aima‘a always said, Once a cup of water is spilled, it can never be retrieved.

Suddenly Mr Viliamu said, You’re quiet again. I can tell you’re thinking about something because your forehead looks wrinkled.

Ha, I laughed, nervously, touching my forehead.

Really? You can do that? Know from my forehead what I’m thinking about? I asked rhetorically this time, not really expecting him to answer.

I looked out the window so that I could catch a glimpse of my forehead in the mirror to see what Mr Viliamu meant. But Mr Viliamu told me that there was a mirror right above me and reached across me to fold it down. His arm brushed lightly against my left breast and a tingling sensation surged through my body, from my head to my toes, which had never happened to me before.

Oopsy, said Mr Viliamu. He looked at me and smiled.

I’m sorry, love, as he returned his arm to his stomach, caressing it, moving it towards his inner thigh, circling his pubic hair, this time, looking directly into my eyes.

Perplexed, I tried to avoid his gaze and the piercing effect it had not only on my own eyes but on my entire body.

What is happening? I asked myself, as I closed my eyes and felt the sensation of Mr Viliamu’s arm against my breast, not to mention his penis, which had increased immensely in size, bulging under his

shorts, which I was trying desperately to avoid seeing.

Is this osmosis? Is this symbiosis? Is this reproduction? Is this metamorphosis? What is this? I could not find a single process in Science to name what was happening to my body and how it was responding to Mr Viliamu’s.

Nor could I comprehend how Mr Viliamu’s body was reacting to my own body.

What process was this? Really? Could I call it a chain reaction? Was it a voluntary or an involuntary muscular response? But to what, exactly?

I did not know. Suddenly everything became a great big blur and for a moment I was swimming in a grey ocean, an ocean where there were no waves. No birds. And no blue skies above it.

Despite the haziness I found myself in, one thing remained certain. That the language Mr Viliamu was speaking with his eyes and his hands was an ancient sacred language. A language that had undoubtedly been spoken by our ancestors before us and was older perhaps than the waves and the birds themselves, older even than the big blue sky.

It was a language Mr Viliamu appeared to know intimately and spoke with the utmost fluency. A language I had never spoken before, and yet, I found myself drawn to it mysteriously if not instinctively as if I had a natural propensity towards understanding its nuances and hidden meanings.

I want you to do something for me, said Mr Viliamu. Startled that he finally spoke, I eagerly responded. What is it, Mr—? Mr Viliamu looked at me again. This time, his gaze pierced something in me that was similar to the brush of his arm against my breast. Only this time, I found myself looking boldly back at him as he tried to steer the red pick-up truck while holding my gaze simultaneously.

I want you to stop calling me Mr Viliamu. Why would you want me to do that? I asked myself. But instead, I remained quiet. Then he spoke again. This time, his voice caused the same sensation his arm had caused earlier when it brushed against my breast and his piercing eyes when they looked directly into mine. Only this time, his voice was like a fisaga, a gentle wind that caressed me and caused me to shiver.

I want you to call me by my name, Sia, he said.

But I am calling you by your name, Mr Viliamu, I found myself whispering back at him.

No, Sia, he said, looking out the window as we sighted the town clock, the Burns Philp supermarket and the Nelson Public Library.

I want you to call me Ioage, he said.

Those were the last words he spoke before we went our separate ways, while the sun’s rays danced on the glass of the NPF building windows, its reflection blinding me as I stepped into the street and made my way through the busy crowd, anxiously looking for a store that sold giant white threads, while thinking about seagulls and waves and other unspeakable things that made me grin, inwardly.

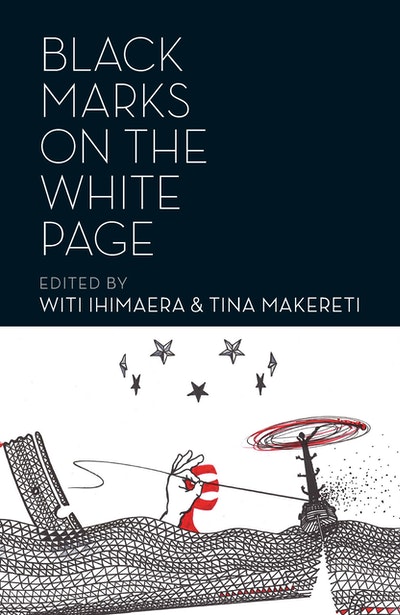

© Sia Figiel. This short story, published in Black Marks on the White Page, Vintage, 2017, is also an extract from Sia’s new novel Freelove, published by Little Island Press, published May 2018: see https://littleisland.co.nz/books/freelove