- Published: 1 May 2013

- ISBN: 9781864712827

- Imprint: Bantam Australia

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 528

- RRP: $28.00

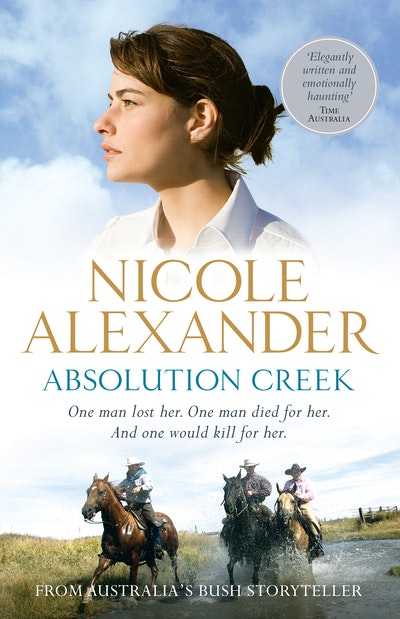

Absolution Creek

Extract

Mills wiped his bloody nose and spat on the road. ‘You always did have a sneaky jab, Jack,’ he complained, his breathing ragged.

‘Ever since you were ten and I stole that bit of bread from you.’

Jack held out a dinner-plate-sized hand and Mills tossed him the shilling coin. ‘That was eight years ago, Mills, and you’re still picking on youngsters.’ Jack turned to a boy who was standing behind him with a loaf of bread and a string of sausages under his arm, and dropped the coin into the lad’s palm. ‘Next time your ma asks you to fetch the bread, do it right quick.’ The sandy-haired kid nodded his head furiously and ran off.

‘You turned into one of those do-gooders, Jack Manning?’ Mills asked. Having caught his breath he was ready for another round.

He lifted his fists; moved his feet from left to right.

Jack rolled his shoulders in anticipation. ‘Don’t you ever get sick of acting the school bully?’

‘Not with you, Jack. You’ve only bested me once.’

‘If you don’t count outing with Mandy Wade. She never did take to you, eh Mills?’

Mills swung a meaty punch, which glanced off Jack’s shoulder.

They circled each other slowly.

‘What’re you doing over here, anyway? Are the pickings getting too slight in your neighbourhood?’ Jack nodded towards the expanse of Sydney Harbour and the Rocks area, which straddled the foreshore beyond. They were standing on the corner of Blue and Miller Streets, a layer of cold glazing the terrace houses and shops that stretched down the hill to the water’s edge. Bunting still hung from the fronts of some buildings following the first turning of the sod for the Sydney Harbour Bridge only a few days prior.

Mills threw a punch that would have floored a bullock had Jack not ducked and landed a swift uppercut to Mills’s cheek.

The Irishman staggered. He spat another wad of blood onto the footpath. ‘I’ve a mind to finish you, Manning.’

‘What, without your pack to back you up?’ Jack gave Mills a spiky jab to the forearm.

Mills wiggled his nose with obvious pain as a shiny black police wagon crawled the length of the street to park a few hundred yards away. ‘You’re always saved from a sound thrashing, Manning.’ Mills gestured towards the coppers with his thumb and, searching for tobacco, nonchalantly began rolling a smoke.

‘They’ll be parked down there for a while, you know,’ Jack informed him.

‘I’ve got time.’ Mills lit his smoke and nodded at the bunting.

‘This bridge’ll mean the ruination of the Rocks.’

‘You’ve been listening to the scandalmongers. I was in the crowd not two days ago. Saw John Bradfield himself, I did. Hundreds of people, there were. There was a band and we all sang “Advance Australia Fair”.’

‘We don’t mean nothing to them toffs. They need a road to get to this here bridge they’re talking about, and my pa reckons it’ll go straight over the likes of us. They’re talking a new railway line and the resumption of houses.’

Jack knew the talk. They too were near the path of the bridge on the northern side. ‘Nothing’s been decided,’ he answered cautiously, glancing down the street towards the coppers who were now chatting to Father Patrick. He was a crafty one, Mills. ‘Why are you over here?’

‘Thought I’d go aways a bit and find work in one of the northern suburbs. Maybe wood chopping, timber carting, that sort of thing.’

He snorted once, twice; the mucus landed glistening at Jack’s feet.

‘Why wait for the rest of the family to be turned out with this bridge debacle? That’s not for me. Figured I’d try my luck without the rest of them riding my heels.’ Mills rubbed his hands together; cracked his knuckles one by one.

Jack could just imagine Mills doffing his cap, a load of firewood under his arm at the door of some gentlewoman in the leafy northern suburbs. He was a heavyset, ungainly man, with a fighter’s busted nose and a face like a partially stretched concertina.

Such looks would hardly endear him to the gentrified. ‘Well, good luck.’ Jack gestured over his shoulder.

The constables were out of the van and stretching their legs.

The priest could be heard laughing.

Mills’s eyes clouded. ‘We’ll leave it for another time then, Manning?’

‘Right you are,’ he replied as they parted company. Although not averse to the odd round of fisticuffs, today Jack’s mind remained fixed on a rendezvous of a far more pleasant kind.

Jack dabbed at his cut lip with a handkerchief before checking that his shirt, waistcoat and suit coat were presentable. He glanced down the street in both directions. Their meeting place was a shady tree a good block from Olive’s parents’ home. Rubbing his hands against the cold he tried to calm down a little. He wasn’t a kid peering through a lolly-shop window any more.

Olive was waiting for him, wearing a drop-waisted beige dress and long coat. A green clouche hat sat low over her eyebrows. Jack was fascinated by her shapely ankles, and silently blessed the new fashion for shorter skirts. ‘Buy you a soda down at the arcade,’ he said, trying not to stare too admiringly.

Olive slipped her arm through his. ‘What happened to your lip?’

Jack feigned ignorance. ‘Oh, that. Knocked it at the store. It’s nothing.’

‘Hmm. Well, I’ve news. I’m to start at Jessop’s Hairdressing next week. I’m to be a trainee.’

‘You? Working for Mrs Jessop?’

‘Jack Manning, women have been working in earnest since the war began, and they’ve kept on working.’

‘I didn’t mean that. I meant your parents.’

‘Oh, I’ll tell them and they won’t like it,’ Olive replied firmly.

‘They don’t want me to work. However, everyone is out doing something and I am nearly seventeen.’

‘Your sister isn’t working,’ Jack pointed out. Still, he admired

Olive’s determination to be like everybody else. She’d read Latin and studied home sciences at a private girls’ school, yet here she was by his side talking about getting a job.

‘What they won’t like is my employer. Mrs Jessop runs a boarding house in Blue Street as well as her hairdressing business.’ Olive pinched her nostrils together and crossed both her eyes as she looked down the bridge of her nose. ‘So lower class,’ she mimicked her mother.

‘Olive Peters, I’m shocked.’

They walked briskly across to Alfred Street, careful of the tram rushing down to the Milsons Point ferry terminal and wary of the horse-drawn carts, cars and light trucks heading in a myriad of directions. Olive stared at the large terraces with their twenty-foot frontages, and smiled at a uniformed maid sneaking a quick puff of a cigarette outside. There were children returning from school in straw boaters, with long socks and school satchels; and the odd dray and horseman trundling slowly uphill, having recently disembarked from a punt. The hot-food shops began soon after. Jack felt his stomach rumble as he smelt pies and toffees and fish and chips.

‘No you don’t,’ Olive cautioned when his feet strayed towards a vendor spruiking the catch of the day.

They tarried outside shop fronts as Olive admired hats and stockings, blouses and dresses. ‘There always seems to be a lot of beige,’ Jack remarked as she marvelled at a white silk clouche hat for sale at over one pound.

‘They say that there is so much khaki dye left from the war that we’ll be wearing beige until the thirties. Don’t laugh, it’s true.’

Jack looked pointedly at her ankles. ‘War shortages and oversupply, eh? Well, I’m happy with that.’

Olive tugged on his arm. ‘Scallywag.’

He wrenched her away from a window display of flesh-coloured stockings.

‘Why, I do believe you’re blushing!’ she teased.

‘That’s a bit modern.’ It was one thing to show a little leg when covered in black, tan or white, but flesh-coloured? He wasn’t a wowser or a moralist, however it made him uncomfortable to think that the likes of Mills McCoy could glimpse his girl’s ankles.

‘Come on.’

Together they walked downhill, the winter cold seeping up from the cement beneath. A clear view of the harbour lay before them, the water gleaming grey in the late afternoon light. Across its surface the wakes from the many craft crisscrossed each other like streamers. Jack tried counting the vessels on the busy waterway but gave up at thirty-five. There were numerous ferries, punts and barges, small boats and the Union Steamship Mail Boat. Puffs of black smoke trailed the larger vessels, ruining what was otherwise considered a fine view.

‘Imagine being able to cross a bridge to the other side, Jack. Why, we’ll be able to walk straight across to Circular Quay.’

‘It’s a mighty endeavour,’ Jack agreed. ‘It’ll bring changes, though.’

‘Father says it’s all for the good. The harbour is an accident waiting to happen, what with the number of craft. It’s bad enough during the day, let alone when a fog comes in. Then the only things people have to rely on for guidance are fog horns and bells.’

Jack had heard the benefits of the bridge orated by a master.

Mr Bradfield possessed an uncanny ability to glorify his proposed engineering marvel so that many Sydneysiders thought it to be a wonder of the modern world. ‘Sydney has always been like two distinct towns,’ he reminded her. ‘Here in the north it’s quieter, safer. In the still of night you can hear the animals at Taronga Zoo.

It’s like a frontier.’

Olive’s neat eyebrows knitted together. ‘Who wants to live in a frontier country? We’re city people, and soon we’ll be living in the most wonderful city in the world with the most marvellous bridge spanning the harbour like a rainbow.’

Jack rolled his eyes. ‘We already have five bridges.’ He counted them off. ‘Pyrmont, Glebe Island, Iron Cove, Gladesville and Fig Tree.’

‘Yes, but we don’t have one here,’ Olive reminded him.

Ahead lay Milsons Point wharf. There were ferries ploughing across the harbour, and in the distance a steam train snaked towards them from Lavender Bay. They walked through a queue of cars and drays waiting for the next punt, as a tram left the open terminus and shuddered past them uphill. At the soda bar Jack found a little wooden cubicle near the front of the shop. Patrons were lined up along the shiny black counter on tall stools, each slurping the latest drink from America. The soda pumps buzzed noisily. There was the clink of glass and the friendly hum of conversation.

‘What you be having then, lovey?’ The waitress was poised before them with pen to paper.

‘I’ll have a Delmonico Banana Sundae,’ Olive replied.

The waitress looked at Jack, scratching her hairline with the stub of her pencil.

‘To share,’ he replied, patting the coin in his pocket. It was an expensive business this outing with a girl. ‘What’s in that?’ he asked as the waitress departed.

Olive ran her finger down the menu. ‘A split banana on a lettuce leaf with two serves of ice cream atop it. One side of the ice cream has crushed maraschino cherries over it, the other crushed raspberries.

It’s finished with whipped cream, chopped nuts and a cherry. It’s delicious, Jack. I had one with my sister only last week.’

‘Trust the Americans to ruin a good ice cream.’

Olive’s foot jabbed Jack’s ankle.

When the concoction arrived Jack dived in, shovelling spoonfuls of the sickly cold mess into his mouth. Soon his stomach began complaining and he let Olive finish the dish.

‘You know Mrs Jessop promises to train me quickly.’ Olive licked her spoon. ‘She says that at the rate women’s fashions are evolving there will be a totally new hairstyle next year.’

Jack edged a little closer to her on the bench seat. He made a show of stretching and then rested his arm behind her. The crowds began to rush past the shop’s entrance: labourers, office clerks and secretaries all hurrying through the terminus. Ever since Bradfield’s announcement, Jack’s own view of the world had changed. It was as if, having picked up on all the excitement that such a grand scheme offered, his options now appeared limitless. The war was a distant memory and this new world was transforming every day.

Olive settled back into the seat, dabbing at her mouth with a napkin. ‘It’s getting cold.’

He slid his outstretched hand along the top of the bench seat, his fingertips touching her shoulders. He wasn’t much for public displays and he knew his mother, bless her memory, would be appalled at such conduct. Unfortunately, although public desire was socially unacceptable, today it would fall prey to uncontrollable need. Jack’s thoughts were fixated on a kiss. Indeed he’d been thinking about Olive’s fleshy pink lips for nearly a month since his last attempt whilst picnicking at Lavender Bay. In hindsight that Lavender Bay effort was poorly timed, coming only a week after their meeting, so he couldn’t blame Olive for being shocked. Still, he believed if they kissed again, properly, some of what he was feeling would seep into Olive’s heart. Surely she felt the same way. Otherwise, why else would she be spending time with him?

Her wide grey eyes were fixed on the harbour beyond. ‘We never would have met if you had not been on Alfred Street that day, Jack.’

‘Saving women from ill-tempered Clydesdales is my specialty.’

He leant towards her, tentatively.

‘Really?’ Olive teased.

You can do this, Jack told himself silently. He ran his forefinger across the smooth arc of Olive’s cheek, touched the blue vein throbbing rapidly at her throat. Olive retreated ever so slightly. Sensing her reluctance, yet committed to action, Jack took her hand. His feelings for her went beyond class and common sense. Despite the people milling about them he hugged her close to his chest, his mouth finally touching hers. The pain of his cut lip sealed the moment. This then was their bridging.

When he finally released her, Jack searched for a few words, his brain as capable of sense as the melted remains of the banana sundae sitting before him. Olive looked stunned. A crack of thunder sounded and the sky deepened to a nasty blue. Through the soda bar’s window a bank of angry cloud signalled a squall. Lost for words and with an equally silent companion, Jack scattered some coins on the table and laced his fingers through Olive’s. Now, he decided, was the time for a suitably appropriate comment.

‘Come on, let’s get you home.’

Absolution Creek Nicole Alexander

One man lost her. One man died for her. And one would kill for her ... From Nicole Alexander, the 'heart of Australian storytelling', comes a sweeping rural saga spanning two generations.

Buy now