- Published: 2 July 2019

- ISBN: 9780143792208

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $40.00

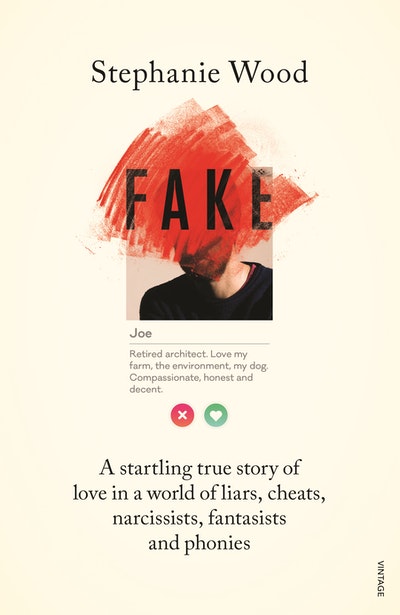

FAKE

A startling true story of love in a world of liars, cheats, narcissists, fantasists and phonies

Extract

I wanted to arrive unnoticed. I’m looking for a man, or traces of him, but I don’t want to see him. I’d even considered wearing a wig. But my car’s discordant chorus is such that I might as well have hired a brass band to trumpet me into this country town on the New South Wales Southern Tablelands. In a dry paddock dotted with rusted farm equipment sheep lift their heads; a boy on a bike in the main street pauses his aimless circling to stare; a bloke in a beanie stands in the driveway of the service station and watches as I scrape and grind to a stop.

He takes a couple of steps towards me and I wind down my window. ‘You’ve got a problem there,’ he says. His mud-splattered truck is parked at a petrol bowser. A kelpie stands alert on the back, tied to the truck’s bars. I’m flustered: the last noisy miles into town have shaken me and now I’m here, 100 metres from the motel I’m afraid of returning to, and there’s no running away from the decision I’ve made to come back.

‘I know, I know,’ I say. ‘It started on the highway . . . scared the life out of me.’ I get out of the car. The wind is icy.

‘I’ll take a look,’ he says. The bloke is young, well built, fetching in his roughness. A hint of flannelette shirt at the collar of his sweater. Open, unlined face and square, stubbled jaw. I can’t stop looking at his hands. Powerful, leathery, the dirt running through crevices of heart, head, life and fate lines, a map of honest exertion.

‘Oh, would you?’ I thank the man and he asks me to drive over to a patch of grass at the service station’s edge. There, he lies on his back and thrusts his head under the front of the car.

‘Nothing major,’ he says, showing his face again. ‘Just a splashguard panel . . . can hold it up with a cable tie . . . always carry some.’ He swings himself upright and goes back to his truck, rummages in tool boxes. The kelpie whirls in excitement, its lead jerks it back. The man ignores it, returns with ties and a knife, and in a minute my undercarriage is stitched up.

‘Good to go.’ I gush thanks. ‘No worries,’ he says, seemingly uninterested in small talk. I try to make some, as a way of leading into a bigger question. I introduce myself, extract his name. It’s Des. He has a farm in this district. Sheep. Merinos. Loves the work. It’s Sunday, nearly lunch, and he’s heading out to bring some sheep in.

I tell him I’m a journalist and that I’ve come to town to look for a man. It’s a strange, awkward thing to explain, but Des seems to get it. I tell him about the man – that he said he too had a sheep farm here, a few hundred acres. Said he fattened dorpers for the Chinese market on land out this way.

‘Dorpers, eh,’ Des says. ‘Not many of them round here.’ I don’t tell him that the man scoffed at merinos and said that dorpers – a hardy South African breed that thrive on native grasses and shed their fleece – were where the money was. Des doesn’t need to know the details: that I once believed that when the man wasn’t in the city making love to me, or raising his two children and protecting them from his crazy ex-wife, he was here. Regenerating his land with native grasses, bringing eroded waterways back to life, building fences, slashing sifton bush, shepherding his dorpers; and then, at night, filthy and bone-tired, drifting off to sleep in a rough shack with a fire blazing and his kelpie at his feet. Dreams in his head of me and the house he had designed, which he would soon build on his land beside the rubble of a 100-year-old stone cottage near a crumbling headstone standing sentry over the diminishing bones of some colonial tragedy.

‘Nah, don’t know him.’ Des studies the photograph I show him, registers the name I mention. ‘Sorry. Haven’t seen him round here.’

•

I’d hate to be misunderstood: I’m looking for a man but without the least romantic intent. It’s long over. These days, more than a year since we parted, I think of him as a specimen. Today I’m on a field trip to study his habitat. But I’m jittery; I do not want an encounter with this creature. Once, in his smiling eyes I saw good and gentle things. I held him tight and hoped for so much. Now I know that the smile was a simulation, the eyes black holes. I know to keep my distance.

My undercarriage restored, I drive out of town. I want to find the land and the shack. If I can find them, I will get closer to the truth. The property was the first thing the man told me about the day we met, his foundational story: the land was his purpose, the shack a cocoon in the aftermath of a bruising divorce, his work here an alibi for his absences. In emails, he wrote of this place as he might a lover, my rival for his affection: ‘I am off to my part of the country . . . the itch of not being there is getting to me.’ He described in evocative detail the challenges and joys of his farm: the heavy rain that had brought trees down on fencing he would now be kept busy replacing, the lush grass that had given his stock the runs ‘in a biblical-tide-like catastrophe’, how he would need to bring them in for drenching. ‘Oh, the joy of that, as more than a thousand of the shitty things push up against me in the race.’ On the afternoons he left Sydney to drive to the farm, he would text me photographs – his Land Rover Defender’s bonnet cresting a hill, a golden sunset dropping into the earth. ‘Nearly home.’

By the time the man brought me to see the land and shack, months into our time together, I had surrendered and did not think I would ever need to find my own way again. In the cab of his Defender ute, his red kelpie squirmed at my feet and I let my head rest back, soaked up sharp-blue sky, gum-tree blur, white cockatoos rising, sweet magpie song. Such dreamy content: this man beside me, this country, these paddocks, that little creek, that box gum with the undulations in its trunk like the plump rolls of a baby’s belly. I felt I was folding into him, folding into the landscape. But I wasn’t paying attention to the road.

Now, I am trying to find my own way: I try to feel the route he took to the shack. I recall a hairpin turn out of town over a stone railway bridge, a straight stretch through the bush for some kilometres, then a Y in the road. Here now, here is a Y; I take the right arm onto a narrower, pock-marked road and it feels correct. At some point along here we went through a gate on the right, then climbed a winding track up a hill. Here is a gate now and, beyond it, a hill. This feels right. I get out, open the gate, return to the car, drive through the gate, get out, close the gate, return to the car, take the dirt track up the hill, tyres slithering, my little car unhappy with this work. It’s a dead end. I return to the road and drive on, and open and close other gates and take other rough tracks up other hills. I find an Angora goat stud and conservation management zones and a building site, but I cannot find the track with the shack at the end of it and my unease is growing; I don’t believe the man will be here, but what if he is? The light is fading. I check, more than once, that my car’s doors are locked. I pass a little old cemetery. I come upon a sign pointing up a side road on the right. A sign on the gate across the road says ‘Sheep grazing: please drive with care’. Now I know the way. Gate, track, dirt, hill, rut, dust, cattle grid, jolt, bend, bump.

And there it is, the enchanted abode: a squat, square brick and corrugated iron shack with a chimney tacked to the side and a bloom of rust. A scrubby hill rises behind it; a wire fence encloses it, separating the rough structure from both the track I’m stopped on and a neighbouring property and its alpacas, sheds and bullet-peppered sign (‘NO TRESPASSING: Violators will be shot. Survivors will be shot again’). I survey the scene from my car. It is all as I remember but for an unfamiliar white ute parked beside the shack. Someone is there but I feel sure it’s not him. As before, I will not be going inside.

By the time the man finally brought me here, he was reminiscing. By then he had, he said, sold this land and shack and a new owner had taken possession; the man had a new, grander passion in his sights – he was negotiating to buy a substantial property closer to Sydney. He idled the Defender in about the same spot I’m paused now with my engine running. He looked at the shack and talked of his sadness at leaving this place, ‘where the landscape is familiar, and the people know me’.

Now I have the map coordinates I need to do a land title search. As I drive away, a cloud of dust rises behind my car and I flick on front and back windscreen wipers. In my rear-vision mirror the shack recedes, framed by a smudged arc of filth left by the wiper. Before me, the late-afternoon sky glows pink, a rosebreasted cockatoo swoops low and kangaroos startle and bound away across paddocks. But the rosy fantasy is gone. I can see everything clearly now: the shack behind me is pathetic, the land around it harsh and degraded.

A thought flashes into my head: I stop the car, pull out my phone and find a photo of the shack the man sent me during the early days of our relationship. ‘Abode’, he typed. I zoom in and notice something I missed before: the wire fence is in the foreground of the photo. He must have taken it from the track where I stopped moments before. He did not send me shots of the shack from any other angle, or of its interior. Could he have invented his ownership of it and the land? Perhaps he was never more than a sightseer in this place, never slept in the shack, never fenced or drenched or jostled here with a thousand shitty sheep.

•

I hoped to slip in quietly. I thought I might order a shandy, hide in a corner and plan how I could continue my research, ask the locals some questions, without appearing like a romantic halfwit. But at this little hotel in a hamlet a short drive from the shack, the low-ceilinged room is intimate, the Sunday-afternoon session poorly attended and I’m an instant curiosity. When I open the door, heads turn, mouths gape. I scan for the most sympathetic face: a tiny older woman behind the bar. I order a drink, she asks where I’ve come from. I murmur an explanation – if I’d bought the Brooklyn Bridge I could not feel more foolish.

‘Everybody, meet Stephanie,’ the woman broadcasts to the half-dozen or so drinkers. ‘She’s looking for a man.’ I’m reminded again of the fact that I won’t be able to reach any understanding of this episode of my private life without revealing myself publicly to one degree or another.

I introduce myself to the drinkers. They’ve clearly been at it for a few hours. Flushed faces, a mist of bonhomie settled upon them. I reach for my phone, pull up a photo of the man, pass it around. People peer at it, shake their heads; one bloke, bottom drooping over his barstool like a Salvador Dalí clock, thinks he might have seen the man before.

‘Know that face, darl?’ he asks a woman passing behind him on the way to the bathroom. No, she doesn’t. I drop the man’s name; no one knows it. In the man’s story, his property was at one point in a Southern Tablelands triangle of cheer in which the other vertices were the country town, with its motel, pub and cafe, and this hamlet and its tiny hotel. In another century, bullock carts and carriages and horses tied to hitching posts idled outside a flourishing public house; in this century, the hotel is a scrappy hold-out in the face of rural exodus. The man introduced the hotel to me early in his story: in a text message to explain his online dating profile photo he wrote that he’d ‘scrubbed up’ to go there for a drink and a steak. In the photo he wore a checked shirt, battered Akubra and a sullen expression that I chose to interpret as brooding. The man in the photo was lean. When I met him a year or so after the photo had been taken, his physiology had set a course towards dissipation: some drooping in the jowls, a swelling belly tucked in behind shirt and trousers, and strapped in by a plaited leather belt – a costume for the role of a countryman. ‘My goodness, I was hands-on then,’ he wrote. He vowed he’d drop 15 kilograms.

‘Curiosity killed the cat, you know,’ says a woman with messy short hair. She’s in jeans and work shirt, and stands with her backside to a wood-burning stove. The bar laughs as one. ‘How long ago since you seen this fella? I reckon he’s leading you on.’ On my phone, I pull up a photo of the shack. She looks at it, shakes her head, passes the phone on.

‘Reckon he led her on, well and truly,’ says a bloke with an unloved beard, hooting with laughter, all cockiness and broken capillaries, the room’s ringmaster. ‘Most likely took a photograph of someone else’s house.’ The drinkers cackle with him. I grit my teeth, attempt a smile and roll my eyes towards the ceiling. It’s too low for the man, this room too tight. He would have been trapped here, forced to account for himself; these people would have seen through him immediately.

I tell them where the shack is.

‘The final frontier,’ says the ringmaster.

‘When I was a kid, I used to go rabbiting up there,’ says the man with the bottom.

‘Top little spot,’ says the ringmaster. He has a mate with some land up that way. ‘They call them “blockies”.’ Subdivisions of a few acres, roo-shooting on weekends, cartons of beer, bawdy jokes. I think of the shack, the property next door with the alpacas, and another on the other side of the road flying an Australian flag, its front gate adorned with bleached sheep’s skulls. Farmers grazing sheep on a few hundred acres don’t have blockies as next-door neighbours.

I think of the man’s hands – soft and pale and clean. Once, I asked him how a farmer’s hands could be so fine. ‘I wear gloves,’ he said straight back at me, pointing out his sun-spotted fair skin. A few days later he reintroduced the subject. ‘I’ve been thinking about why my hands are so soft,’ he said. ‘It’s the lanolin in the sheep’s fleece.’

‘But you said you wear gloves when you work?’

‘You can’t wear gloves when you’re working with sheep.’

I think of Des’s rough hands. I think of the man’s swerving, colliding, fantastical stories, the decisions we make about the information that is placed before us and our capacity for self-delusion.

I’ve given the hotel’s regulars enough free entertainment for one day. It will be dark outside now, the road back to the country town is unfamiliar and the day’s challenges are not over: I still have to check into the motel. The ringmaster scribbles down his blockie mate’s phone number and hands it to me. ‘He’ll know if your bloke ever had that shack.’ He shakes his head; he’s softer now. ‘There are a lot of clowns out there who treat women really, really badly.’

‘Lots of roos on that road,’ the man with the bottom warns as I move towards the exit.

‘Got a bull bar?’ asks the ringmaster. A hatchback, I say, and he shakes his head again. He offers advice: go slow, use your high beam, don’t try and dodge a roo because you’ll end up hitting a tree. Better off hitting the roo. He repeats his advice: ‘Do not swerve for the kangaroo. Mow the fucker straight to the ground. Do not swerve, do not swerve.’

FAKE Stephanie Wood

Now a Paramount+ TV series, inspired by the book, starring Asher Keddie and David Wenham.

Buy now