- Published: 3 July 2017

- ISBN: 9780143785552

- Imprint: Random House Australia

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 304

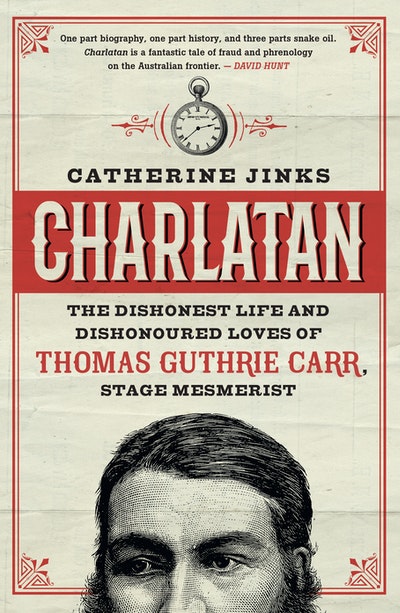

Charlatan

Extract

On Monday 14 September 1868, this middle table was occupied by William Roberts and Julian Salomons. Roberts was a former member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly; among his past clients were bushrangers Ben Hall and Frank Gardiner. A dark and sternly handsome man, he had a big family and an office on York Street. Salomons, aged thirty- three, was slightly more unusual. Short and cross-eyed, with a squeaky voice and a reputation for breaking down mentally after periods of intense work, he had already represented one notorious murderer and would defend several more. But on this occasion his client wasn’t accused of murder. Twenty- nine-year-old stage mesmerist Thomas Guthrie Carr had been charged with felonious assault.

It was claimed that he had mesmerised Mrs Eliza Jane Gray of Botany Road, Chippendale, and raped her while she was under his influence.

During his arrest the previous Saturday, Carr had insisted that Gray was trying to extort money from him.

Then he’d been given bail of two hundred pounds – a rather large sum that Carr appears to have raised without too much trouble. But now he was back in the prisoner’s dock, at the mercy of Police Magistrate Captain David Scott and an array of other gentlemen (including Anthony Hordern, of the well-known retailing dynasty) whose job it was to weigh the evidence against him. If they decided in Gray’s favour, Carr would be committed for trial at the Central Criminal Court. There he would face a possible death penalty, because in New South Wales rape was still a capital offence. In this, as in practically everything else, the colony lagged behind Britain.

Carr’s ‘prosecutrix’, Eliza Gray, was thirty years old, Irish-born and the mother of eight children, one of whom she had already buried. Her husband, William, was away from home a lot; he was a fireman aboard the steamship Lady Young, which regularly plied a route from Sydney to the far-flung, northerly towns of Queensland: Brisbane, Maryborough, even Rockhampton. Presenting her testimony to the court, Gray declared that she worked as a forewoman at the Cohen Brothers’ Monster Clothing Hall. How she managed to hold down any kind of job is hard to fathom; possibly her thirteen-year-old daughter lent a hand with the younger kids.

Gray’s employers, the Cohens, prided themselves on manufacturing ‘the best and most varied stock of Ready-Made Clothing in the Colonies’. They loudly advertised the ‘painstaking labour’ that went into their dress and frock coats, their walking coats, their waistcoats, their tweed and ‘angola’ trousers. Eliza Gray was one of the many women responsible for assembling ‘suits to order, well shrunk, at 8 hours’ notice’. She did this, not at the showroom on George Street, but at a Pitt Street workroom not far from the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts – where Thomas Guthrie Carr had at one point occupied a private office. So it isn’t surprising that when she first saw Carr he had dropped in to order some clothes.

According to Gray he simply came into the workroom, looked at all the girls hunched over their machines, then went away again. But she would have noticed him at once because of his height. Carr was very tall. Years later, in New Zealand, a journalist would describe him as standing ‘above 7 feet in his stocking feet’. This may have been an exaggeration; the tone of the entire article was facetious. But the New South Wales Police Gazette gave Carr’s alias as Long Tom – and one Sydney columnist, writing in 1899, remembered Carr as a tall, big man of ‘coarse and sensual, but not unprepossessing’ features.

In New Zealand, especially, the height of the ‘giant doctor’ was often remarked upon. During an assault trial in Wellington, one witness declared that he would not like his nose to be in Carr’s great hand. Another, upon describing how Carr had threatened him, turned to the defendant and said, ‘I’d have given you more than you bargained for, big as you are.’ Long after Carr’s death, an itinerant mesmerist making the rounds in New Zealand was all but commiserated because he wasn’t a big man, as Dr Carr had been.

Carr’s personality was almost as memorable as his height. While some commentators praised his ‘fine voice and pleasing address’, declaring that he possessed the art of saying just enough and no more, others seemed overwhelmed. ‘As a lecturer, he is perhaps too voluble and demonstrative in his gesticulations,’ one observer remarked, though another complimented Carr on ‘his familiar off-hand style, his nonchalant air, and his fluent disquisitions’. Certainly his delivery must have been unique. In 1872, at a benefit concert in New Zealand, an impersonator gave an impression of Carr that delighted the whole audience. Apparently the mesmerist was a very fast talker – or perhaps it was his vocabulary that set him apart. ‘He is never at a loss for a subject upon which to discourse,’ Wellington’s Evening Post observed, ‘and has a greater flow of language, and uses a larger number of extraordinary and almost impossible-to- understand words and phrases, than any person in the colony.’

There’s also evidence that Carr’s pronunciation was unusual. One Melbourne commentator remarked that ‘a person who pretends to lecture on “Science and the Bible” and pronounces Thales like Wales, and Seneca with the accent on the second syllable, and Caligula with the accent on the penultimate . . . must surely be undertaking a task for which his education at all events has not fitted him.’ Another infuriated columnist made a list of Carr’s errors: ‘Dante’ became ‘Dant’, ‘Barnabas’ became ‘Banabas’, ‘indelible’ became ‘indelia’ble’, ‘sol’ace’ became ‘so’lace’ and ‘envel’op’ became ‘envol’op’. The same correspondent was also in a frenzy of irritation about Carr’s gestures, which were likened to the sails of a windmill, or the jerking of a pump- handle: ‘His gesticulations, on several occasions, wore all the appearance of an enraged ourang- outang.’

Carr was loud in every sense. One detractor described him as a charlatan with ‘a bold front and a long tongue’, who had ‘plenty of wind to blow his own trumpet’. He liked to talk. He had ‘the gift of the gab’. And when Eliza Gray saw him for the second time, just a day after her first glimpse, he subjected her to the full force of his persuasive powers.

She testified that she was called down to the shop, where Carr was waiting. He told her that she would make a good subject for one of his séances. Gray retorted that she didn’t want to be mesmerised.

‘Why not?’ he asked, taking her hand. Before she could answer, he reeled off a list of the people he’d worked with, though she couldn’t (when pressed) remember their names. Possibly some of them were female and he was trying to convince her that any number of respectable women had survived mesmerism unscathed. But even this argument didn’t change her mind. Finally, he begged her to attend one of his shows. If this invitation included a card of admittance, Gray didn’t mention it – though she was careful to report that he gave her one at a later meeting. So it’s possible that when she did go to his first séance, she paid for her own ticket.

A shilling seat at an evening performance can’t have been easy to justify for a working-class mother of seven. Carr must have made quite an impression on Eliza Gray.

His opening night was scheduled for Wednesday 1 March 1868, at the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts. It had already been widely advertised as the first in a series of ‘phreno-mesmeric, electro-biological and electro-psychological seances’, in which volunteers from the audience would either be mesmerised or have the shapes of their heads assessed. (Electro-biology, electropsychology, animal magnetism and mesmerism were interchangeable terms at the time – but they certainly sounded more impressive when they were all piled into one sentence.) ‘SENSATIONAL CLASSIC TABLEAUX’ were promised, ‘exhibiting startling statuesque effects, with wonderful manifestations of the varied passions and emotions of the human soul’. There would also be music from a ‘first-class artiste’. Doors would open at 7.30 pm, for an eight o’clock start. Tickets were one shilling for the gallery, two for the body of the hall and three for reserved seats.

In addition to running newspaper advertisements, Carr had probably distributed coloured posters and handbills, as was his habit. Some of his posters would surely have been hung around the entrance to the School of Arts – a dignified, sandstone-faced building wedged in among a variety of shopfronts on Pitt Street. While many of the ‘splendid establishments’ occupying this thoroughfare had been favourably compared to those in Liverpool, Pitt Street was not lined with such fashionably uniform facades. Instead, the occasional four- or five-storeyed structure towered over a patchy array of neat little inns and fruitshops. ‘It is not what an architect would call a fine or imposing style of street architecture,’ travel writer John Askew confessed, though he hastened to add that the contrast was pleasantly free from ‘monotony’.

The School of Arts was one of Pitt Street’s more impressive additions, erected as part of the mechanics’ institute movement, which was founded to create a scientifically educated artisan class. The building contained a variety of rooms, including a chapel, a reading room and a lecture theatre. When Eliza Gray visited Carr there, shortly before his first show began, she was ushered into his private office and introduced to a young woman named Brooks. According to Carr, this woman had agreed to be mesmerised. She may very well have been the same ‘young lady somnambulist’ who later appeared in the Newcastle shows of one R Rupert Ewen. ‘Somnambulist’ was a term often used to describe a mesmeric subject, because such people were cast into a kind of waking sleep; Ewen’s female somnambulist was supposed to have performed at Carr’s séances in Sydney for at least a month before her trip to Newcastle, so she must have been regularly mesmerised by Carr, and probably had the run of his rooms – just like Miss Brooks.

Whoever Brooks was, however, she failed to convince Eliza Gray to join her on stage. Gray remained in the audience that night.

But Carr wasn’t lacking in subjects. When describing his first séance, the Sydney Morning Herald noted that, towards the end of the show, ‘a dozen young men from the audience, having placed themselves under his influence . . . proceeded to . . . perform the most ridiculous actions, believe the most absurd things, and so on.’ The greater portion of the evening, however, was devoted to a lecture on the ‘science’ of phrenology. Phrenology was a diagnostic system based on the notion that a skull’s shape was determined by the kind of brain it enclosed – so Carr invited two women and about eight or ten men up onto the stage, where he examined their heads to ascertain their most prominent characteristics. He also compared the various human skulls in his collection, demonstrating how some had fully developed ‘intellectual and moral faculties’, while others did not. ‘The audience appeared to be deeply interested in the remarks of the lecturer, who is evidently well up on the subject,’ the Herald reported.

The most amusing part of the show, however, featured Carr’s mesmeric experiments. One account of a later Sydney performance described in detail what people were made to do when Carr mesmerised them. Some were forced to sing, some to dance, some to recite, some to march in a funeral procession. Two of them declaimed over the motionless form of an Aboriginal boy, who was playing the part of their dead comrade. ‘If any proof were wanting of the power which Dr Carr possesses over those who were on the platform,’ the Herald enthused, ‘it would be found in the tender caresses bestowed by both young men and young ladies upon the aforesaid black boy, who was made to act the part of a delicate young lady.’

Even the Herald, however, was in two minds about the rest of the entertainment. Steel needles were apparently thrust into the cheeks and arms of Carr’s subjects, demonstrating that they would feel no pain during subsequent surgical operations. ‘The cutting out of a tumour . . . is no fit experiment to be performed in the presence of a mixed auditory,’ the Herald complained. ‘Such experiments ought to at least be confined to the drawing of a tooth . . .’

Fault was also found with Carr’s rather cavalier attitude towards his subjects. One man was chased by a mesmerised woman ‘bent upon putting a long needle in his arm’. Other subjects, under the impression that they were mesmerists, caused ‘considerable annoyance’ to people in the front seats after Carr himself had left the hall (apparently without restoring his victims to their senses).

If his first séance was anything like this one, Eliza Gray must have felt grateful that she’d declined to take part.

But later, when he accosted her in the street, she agreed to visit him at home. He wanted to see if he could mesmerise her, he said. Some might argue that she was already mesmerised; why else accept such a dubious invitation?

Luckily, she had the wit to take someone with her. On her first trip to Carr’s lodgings, she was accompanied by nineteen-year-old Elizabeth Hook – another Cohen Brothers’ employee. At the time, Carr was living in Elizabeth Street, the most ‘comfortable’ address in the city outside of Wynyard Square. The two women, however, stayed for only a few minutes. ‘Let me see if you are good subjects for mesmerism,’ he said to them. Then he laid his fingers on their eyes and announced that they were, indeed, good subjects.

They left soon afterwards, with his cards of admittance in their hands.

But Hook’s account of the evening differed slightly from Gray’s. As far as Hook could recall, Carr had said that she wasn’t a good subject, because she laughed too much. He had also said that he couldn’t mesmerise her against her will. And he had written something on a card that he’d given to Gray, asking her to call on him again at the School of Arts.

From Carr’s house, Gray and Hook had then gone to the older woman’s lodgings at 74 Liverpool Street, just a few minutes’ walk away. They had eaten supper together at about nine o’clock. After forty-five minutes or so, Hook had left – though there was some confusion about this, too. ‘I swear I did not go back to Dr Carr’s after leaving Miss Hook,’ Gray insisted, after questions were raised about Hook’s original version of the same evening. When cross-examined, Hook declared, ‘I accompanied Mrs Gray from Dr Carr’s to her house, and left her at her own door. I am quite positive of this. I had supper with her afterwards. I went home and came back after tea, and we went around the town . . . I did say I did not see her again that night, because I did not remember it. I was confused the other day.’ Later in her deposition, Hook calculated that she had gone home for her tea between six and seven o’clock.

She agreed that this had all happened ‘on the day the Duke was shot.’

Charlatan Catherine Jinks

The story of a nineteenth century court case involving Thomas Guthrie Carr, a notorious, larger-than-life character who made his living as a mesmerist, phrenologist, public speaker and some say charlatan.

Buy now