- Published: 3 September 2019

- ISBN: 9780143773030

- Imprint: RHNZ Vintage

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 448

- RRP: $40.00

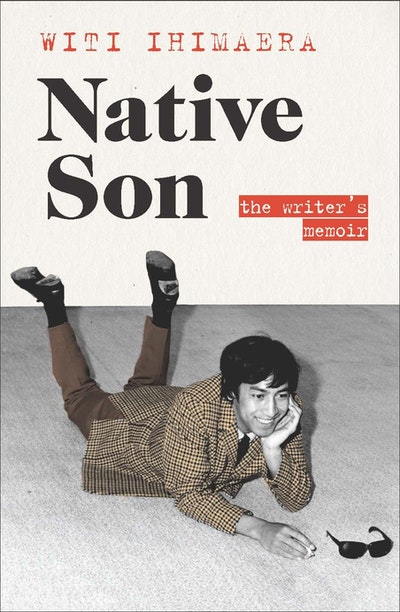

Native Son

The Writer's Memoir

Extract

At that time, Te Karaka District High School was a rural school, which, looking back from the present, existed on the faraway edge of the decile, but a pass was a pass no matter how hopeless the hōri or hick the town. Fifth- form School Certificate was as high as you could go as there was no sixth form. Anyway, that would be pushing your luck. Therefore, despite the usual ambitions I had in common with other boys, such as becoming a jet fighter pilot (we did have one in the family, my uncle Baden), my reality was that I would leave school and help Dad on the farm like Keith and David Wright on the landholding next to ours.

To be frank, although I had not taken to agricultural work as to the manner born, I was fond of farming. I don’t know why as there was nothing romantic about working the land. Season after season, doing the same repetitive work. Buying the cheapest stock and hoping that cattle grown on sparse grass would bring maximum gain at the annual sales. In summer, mustering the sheep to move from one paddock to the other. Watching cattle dying in times of drought, that was hard to bear. Or losing lambs even after we’d pulled them out of their mothers. We’d blow into their nostrils to help them breathe the chill air only to feel the slight shiver in their bodies, the sign of impending death.

Then there were the usual chores that my sisters and I had to do before we caught the school bus. We were up at five to light the fire, get the stove going and lay the table for breakfast. My sisters Kararaina, Tāwhi and Viki squabbled over who would take our baby brother Derek from his cradle, change his nappy and feed him. Meanwhile, morning and night, I shared milking, chopping wood, the occasional slaughtering of an animal for its mutton, and other heavier farm duties with my cousins Ivan, Miini, Kiki, Tom and Uenuku (Banana). And when we returned home from school in the afternoons, there were always other jobs to do: fencing, boiling offal for the dogs, daubing maggot- infested sheep with tar or tending the vegetable garden. Sometimes we did the work under instruction from Dad, Uncle and the grizzled old farmhand, Bulla, who had turned up one day looking for work — and stayed. The three men were weaning us from their care, waiting for us to do the tasks whether they did or didn’t ask for them to be done.

Constantly balancing profit and loss put paid to any notion that farm life was easy. However, there was something about the physical nature of farming that appealed to me. There was also the ambition of working beside Dad and Uncle Puku to raise Maera Station out of its dire finan-cial situation; all our livelihoods depended on that. Actually, my mother was probably more committed to the farm than we were, and it wasn’t a fantasy for her. She loved the life, really loved it, and because she toiled hard on making the farm pay for itself, my sisters and I tried our best to make that a reality for her.

When Dad bought the landholding, nothing had been done to main-tain the quality of grass, and even the pasture we already had was being encroached upon by huge swathes of gorse. I dreamt of modernising the farm so that it was the Māori equivalent of the Ponderosa. I pestered Dad and Uncle Puku about topdressing, upgrading the shearing shed and bulldozing a wide access road to the “Other Side” where the stock was; Bulla, sitting on his horse and rolling himself a cigarette, would listen on, amused.

I must have been an irritant to Dad as he already had these ideas himself. Possessing no capital, however, he maintained the farm the hard way with antiquated machinery and — until that bulldozer eventually materialised — shifted the stock along the narrow track and herded the animals one by one across the swing bridge. Sometimes sheep slipped from the track and, if they got jammed on the bridge, I would clamber across their backs to get them flowing again. One misstep and I would be over the sides falling onto the rocks below.

Every summer, our holiday was to go shearing. Had it not been for the extra income shearing brought in, I don’t think Mum and Dad could have kept the farm solvent. Do you know the story about the Māori farmer and the Texan farmer? The Texan farmer, in trying to explain the size of his ranch, says, “If I travel from sunup to sundown I still won’t have reached the end of my farm.” The Māori farmer sympathetically offers, “Yes, I used to have a car like that.” The implication was that the Māori farmer had improved his lot but, in our case, we still had that car.

My grandmother Teria may have helped Dad to buy the farm, but the capital we put into it was our capacity to work hard and the equity was our sweat.