- Published: 31 January 2023

- ISBN: 9780143776772

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $40.00

The Queen's Wife

Extract

Chapter One

Escape to Whanganui

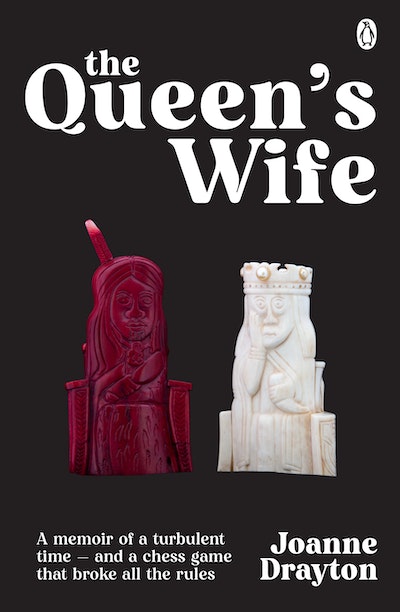

Life is a game of chess. You should try playing it with two queens. People usually see two queens — and no king — as game over. The laws of contest are embedded in its structures, and with a king and a queen on the board heterosexuality reigns supreme. While the queen is arguably the most dangerous piece on the board, protecting the inadequate king is what the game is all about. He moves just one square at a time. Not enough to save himself unless a clever queen, bishop, knight, rook or pawn has his back. Having two queens in courtly love on the board changes everything. The laws of nature are defied. The rules of engagement are tipped upside-down, and each move is uncharted.

I was naïve when I believed I could play on with a queen as a mate as if it made no difference. In fact, the game for me would never be the same again, and no move I made unaffected by this pairing. In the end, life — like chess — is a contest of strategic cruelty, of pieces won and lost, of sacrifices made to survive. This book is the story of a game with two queens, of two women in love, battling to stay together on the board . . .

Visiting the British Museum during a research trip to the United Kingdom in June 1996 felt like being at home for me. Dark, full of treasure: a repository of the world’s wonders. There were things there I had only ever seen as images in books before. The Elgin marbles, the Rosetta Stone, the Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo treasure, and cabinets full of Egyptian mummies. What a complex death, I remember thinking. A body preserved for thousands of years in a swathe of bandages, guided to the afterlife by a book of spells, and an entourage of dead people.

But it wasn’t marbles or magnificent mummified death that transfixed me. It was a weird collection of tiny Romanesque figures called, when I looked down to read the label, the Lewis Chessmen.

They were displayed on a simple chessboard, as if their owners had gone for a moment but would be back soon to resume play. Unlike any chess pieces I had ever seen before, they were Lilliputian-sized human figures, except for the pawns, which were shaped like miniature tombstones. It was the detailing of the faces and costumes that captivated me. This was a medieval world in miniature. In fact, it could have been almost any world — Māori even — where power resided in the hands of the rangatira and the foot soldiers were tribal warriors. The complete spectrum of society was represented from the majestic king and queen to the simple foot soldier.

Thinking back now, I was searching for my own backstory. Digging around in this world-class collection of curiosities as I did as a child in the excavations at Purau, I wanted to discover signs of my ancient past. And I wondered. Did a trace of my Scandinavian ancestors remain in these objects as they did for Māori, connecting the living and the dead? Linking past and present through legend and belief. I felt instinctively that I had found something related to me. Many years later I would have a DNA test and discover that some of my ancestors were Scandinavian. This would confirm what I had already suspected after developing Dupuytren’s contracture — a syndrome known as the ‘curse of the Vikings’.

But in that moment my sense of connection with these objects was visceral. Something that wailed, called and sang songs, that stopped me in my tracks. I wanted to pick them up, to examine them, to unravel their story. But how long can you circle a display cabinet looking with such intensity before you appear odd, or menacing? I glanced around to see if the security guard was watching, and then moved on.

Haunting thoughts of the chess pieces receded after we arrived back in Christchurch, New Zealand. My partner, Sue, and I were moving house. Less than a week after returning from our research trip retracing the footsteps of the New Zealand modernist painter Edith Collier in the United Kingdom, I was shifting to a job in Whanganui. Through our family counsellor, Sue had made a difficult, but we hoped workable, settlement with her ex-husband over custody arrangements for their children. My ex-husband, however, was intractable.

In the four years since we had separated, he had remarried, had another child and I thought moved on from his battle with me. But as we sat in the waiting room of the family counsellor’s office, on the fifth floor of a building later demolished after the devastating 2011 earthquake, I realised this was far from the truth.

It was a bitter July, and ours was the last appointment on a stormy Friday evening. The rain threw itself against the enormous plate-glass windows in sheets; below, the city was a sparkle of watery diamonds in the blackness. I knew Richard was rattled, as he sat apparently calmly reading a Where’s Wally? book from the children’s area — upside-down. We were ushered into the counsellor’s office like opponents on either side of the chessboard, and we matched each other, move after move, for over an hour.

But Richard would give me nothing. No custody of our children, not ever. The atmosphere became increasingly icy. We exchanged threats. It was a stalemate, and, caving into the pressure of the impasse, Trish, the counsellor, abruptly concluded the session and fled the room at high speed with Richard and me in pursuit. I guess we both hoped this finely built, fashionable woman would horsewhip the other into submission.

Outside, the waiting room was silent. The receptionist had gone home. Sue, waiting, looked up at me for any sign of hope.

‘Let’s get home quick,’ I urged her, under my breath. I was terrified that Richard might uplift my two boys and take them back to his place.

I was so relieved when we arrived home and all four children were still there: my boys, Alex and Jeremy, and Sue’s children, Jason and Katherine.

That night and the next day, Sue and I pored over the possibilities. Many variations of our future custody arrangements had already taken shape in my mind and been discussed with my ex-husband. Obviously, shared custody could only work while he and I lived in the same town. Unless some new arrangement could be made, if I left Christchurch, custody of the children automatically reverted to Richard. Now that no agreement had been reached, it seemed only the most drastic options were left. But if I took my children

with me I was breaking the law. I was due to start work in Whanganui on the Monday morning. Now it was Saturday, already. I had no tickets booked, no arrangements made except a car passage on the Interislander ferry. Naïvely, I had believed there would be a resolution.

Sue’s children seemed resigned to their future. While we would see him in the holidays, Jason was to stay with his father, and Katherine would join Sue and me in Whanganui in October. Alex, my elder son, was adamant about staying in Christchurch with his father, but Jeremy, who was ten, was torn between my ex-husband and me. He cried in bed at night over our separation. I was completely conflicted. I couldn’t stay in Christchurch. We were desperately short of money and this might be my last shot at a proper job.

‘Why don’t you ring the lawyer?’ Sue suggested. We had her home phone number. She had become something of a friend over the months of custody negotiation. I agreed. That was the thing to do.

Our phone conversation was ominous from the beginning.

‘If you want to see your son again,’ she told me, ‘don’t leave him behind. The law takes a dim view of parents who take their children, but an even dimmer view of those who abandon them.

‘These things take months to settle in the Family Court. You’ll have Jeremy with you for 18 months, or so,’ she explained. ‘If the decision goes against you, then at least you’ve had that time.’

But it would be expensive, she promised me, and Sue and I were broke. My three years as a doctoral student at university had left us depleted. Years as a clergy wife in the Anglican Church before that meant I had no reserves. ‘The only thing I got from the Church was holey underwear,’ I used to joke to Sue. But financially this was pretty well true.

Eager to share the responsibility of my decision, I asked the lawyer, finally: ‘So, what do you think I should do?’

‘I can’t answer that. In fact, we shouldn’t even be discussing this.’ I’d crossed a line.

‘Okay. So, don’t give me legal advice. Tell me as a friend. What would you do?’

‘I’d take him.’

Our conversation ended there. I didn’t tell her I would abscond with Jeremy, and she didn’t tell me what would happen if I did.

I find peace in motion, so I paced the floor endlessly, getting nowhere. It was Sue who took charge.

‘Why don’t you take Jeremy with you on a red-eye flight to Wellington?

You can catch a bus there and disappear for the day. I’ll drive the car to Picton and take it across on the ferry.’

‘I’m just too stressed,’ I said, paralysed by fear and indecision.

It was early evening when Sue sat down on our bed and began ringing around making arrangements, and jotting down flight and bus times, and costs, on a piece of scrap paper. She booked us under her surname, Marshall, so that Jeremy and I could make our illicit escape to Whanganui. My ex-husband, now no longer a Church minister, used private investigators at his new job at the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), and I knew he was on friendly terms with a number of them. It was possible he had the house under surveillance: my imagination boiled. Had he guessed that I might try and escape with Jeremy? Were they watching us now? Would he try and stop us?

That evening when we said ‘good night’ to the children, it was actually ‘goodbye’. My children both believed they would be staying in Christchurch with their father. Jeremy cried himself to sleep.

Once they were asleep, we packed. I had earlier secretly filled a suitcase full of Jeremy’s clothes and some favourite toys. I now packed my things, and Sue packed hers. Then we tied a giant trunk full of my books and folders of notes on the roof of our Ford Telstar. The car had belonged to Sue’s parents. Her father had been tragically killed, and her mother had died 18 months later. This was one of the few possessions from their estate that became hers.

As I flung the rope under and over the trunk, winding it around and pulling it tighter each time, I thought about things. If this had been my legacy, I would have policed it more fiercely. But Sue had a different way of holding on to things. From almost the first time we met she told me she was Māori. It was part of the family myth. But to look at her this seemed preposterous. Three generations of Māori women marrying British-born men had given her grey eyes and sandy-blonde hair. But beneath her fine-textured olive skin beat the heart of a Māori. Tall, statuesque, she was a woman who walked lightly through the world.

The finishing touches to packing the car were the big, bulky gas heater and cylinder, and my 1989 SE Mac computer, which contained every bad or sublime thought I’d had since the beginning of my PhD.

We went to bed to grab an hour or so of sleep, but there was no sleep for me. Every terrible possibility ran through my mind.

I had gone to bed half-dressed, and didn’t need an alarm clock to wake me, even though I had set one.

‘Sue . . . Sue . . . get up,’ I whispered. ‘It’s time to go.’ We were quickly out of bed. I finished dressing in the dark and slipped downstairs to open the door to Barry, a brave friend of ours who had offered to be there when the children awoke, and when our ex-husbands arrived later in the day to pick up the children.

Sue left first. We opened the doors to the internal garage by hand, and almost soundlessly the car slipped out and down the short asphalt drive to the street.

I scanned the darkness to see if anyone was there. The street was empty of cars. Our duplex was on a slight rise, not far from a corner street-lamp, so it was a handy vantage point. I couldn’t see anything suspicious.

Soon after Sue left, the taxi arrived to take me and Jeremy to the airport. My heart pounded. This was another moment of vulnerability.

I handed the taxi driver our suitcases, and he shut the car door behind me.

‘Now take this and whatever you do, don’t lose it,’ Sue had said as she handed me a scrap of notepaper with all our travel details on it. I didn’t have tickets, just a flight time and a booking number. Now I scrambled around in my backpack, going from pocket to pocket, searching for the piece of paper with mounting desperation. Just before we reached the airport, I found it. I helped Jeremy out of the car, paid the taxi driver, and grabbed our bags.

As the woman behind the counter handed over our boarding passes, I remember thinking that my anxiety must be manifest. But the exchange went ahead as usual.

We were early, so I took Jeremy to the cafeteria, which was just opening up.

‘Have anything you like,’ I said, feeling that this was a moment for mild celebration.

Jeremy chose a large meat pie. Within seconds the pie was being generously covered in sauce spluttering out of a large red plastic tomato. I helped myself to a piece of ginger crunch from the cabinet. But my appetite had vanished. I trimmed off a corner of the slice with a knife and ate it distractedly, all the time watching Jeremy tuck into his pie. His large, chubby hands wielded his knife and fork with awkward determination.

Everything about Jeremy was big for his age. The paediatrician skimming through the wards at Christchurch Women’s Hospital had been stopped in her tracks at the sight of him as a baby.

‘This child will be a giant,’ she pronounced after the briefest look.

‘How can you possibly tell?’ I asked, amazed.

‘Look at the hands, the feet, his length! I’ve seen lots of babies,’ she said as

she turned to go, ‘but he’s going to be huge.’ Initially, I was sceptical, but her prediction began to come true. Jeremy shot exponentially off his Plunket chart. Holding his hand crossing the road was like holding an adult’s hand. When Jeremy came to play, mothers padlocked their refrigerators. But he was sweet, and gentle, and mine — for now.

From the moment I woke him that morning, he seemed relieved. Like some difficult decision had been made for him.

‘Are you sure you want to go with me?’ I had asked him in his bedroom as he dressed and then again at the airport. I knew this was unfair. But for some reason, asking salved some of my conscience.

Jeremy was finishing his pie as the announcement to board came over the loudspeaker.

‘Let’s go, Jeremy,’ I said, picking up a small brown paper bag from the counter and dropping my piece of ginger crunch into it.

My heart pounded again as the woman took our boarding passes, but she just smiled at Jeremy.

The sun rose on our flight to Wellington. It was a magnificent sky of reds, hot pinks, and oranges. I breathed deeply for the first time as the heavenly furnace turned green, then a gorgeous eggshell blue.

When I looked down at Jeremy, he was smiling. This was an adventure for him. Deep down I think he liked the idea that he had been taken: chosen. But he was ever the diplomat.

‘Dad will be okay, won’t he, Mum? He’s got Alex and you’ve got me, and I’ll stay with him in the holidays.’

‘Yes, Jeremy, that’s right.’ And it did seem right to me. But I knew his father would never see it that way. Although it sounds terrible, in reality in custody disputes children are pawns on the board. On one hand they are moved and manipulated; on the other, as François-André Danican Philidor has said, ‘pawns are the soul of the game’.

The Queen's Wife Joanne Drayton

A modern love story: whakapapa, archaeology, art and heartbreak.

Buy now