- Published: 4 August 2020

- ISBN: 9780143774761

- Imprint: RHNZ Vintage

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $37.00

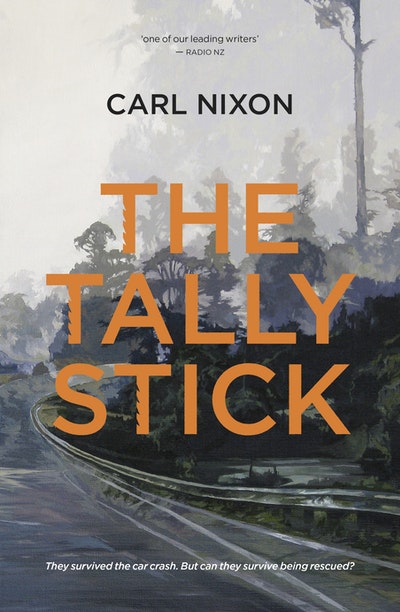

The Tally Stick

Extract

The only person awake was the driver, the children’s father, John Chamberlain. His long, narrow face was visible in the dashboard light. He was staring forward at the headlights as they shone east over the seemingly endless forest, fat, diamond drops of rain slanting through the beams. His expression was, more than anything — even more than fearful — disbelieving. Both hands still grasped the wheel as if he remained in control. Perhaps he believed there might, even then, be a manoeuvre he could perform, a secret lever known only to a few he could search for, yank; something — anything — he could do that might save his family. Behind him, one of the children groaned and shifted in their sleep.

‘Julia.’ John’s voice was a dry whisper.

The children’s mother was next to him, her chin tucked bird-like into her shoulder, head resting on a cardigan pressed against the door. Earlier, she had unbuckled her seat belt — it had been uncomfortable — now it coiled loosely across her shoulder and down into the shallow pool of her lap. She was dreaming about horses. Three brindled mares were wheeling in formation in a dry, barren field. White dust rose around them, swirling higher and higher. Faster and faster the horses ran, as if trying to escape the dust they were throwing into the air. In Julia’s dream, the horses’ hooves were impossibly loud.

John wished there were time to apologise to his wife. He wanted to say sorry for many things: the long hours he’d been keeping at work; that petty argument about the wallpaper; the woman in Tottenham Julia still knew nothing about. Mostly he was sorry for bringing the children to this country. Julia hadn’t wanted to leave London. He’d pressured her: that was the right word to use, pressured — he could admit it now. He’d insisted that this job was a stepping stone. A place to land lightly before moving on. He’d promised her a future with postings to the New York office, perhaps even Paris. They would hire a nanny once they had settled into the new house in Wellington. A picturesque little city. ‘It’s only two years at the bottom of the world,’ he’d said. ‘Think of New Zealand as an adventure.’ In the end Julia had come around to his way of thinking. She was a good wife. A fine mother.

Hours earlier, the family had stopped at a small village to eat a dinner of steak and chips. Julia talked about getting a room for the night. Perhaps they could walk up the valley the next morning with the other tourists to see the face of the glacier? Excited by the idea, the children looked up from their meals.

‘It’s just a wall of dirty ice,’ he told them, pushing aside the plate with his thumb, his food half-eaten. ‘There’ll be nothing to see. Besides, I’m sure this rain isn’t going to stop, not before morning. We should push on.’

John had been told this part of the country was a natural wonder, a remnant of prehistory, but all they’d experienced in the three days they’d been travelling was relentless rain and grey coastline, mountains hidden behind cloud, and undercooked chips. If they’d bought a ticket, he would have asked for his money back. It had been dark when they left the restaurant. As they made the bowing dash to the car, the neon ‘vacancy’ sign outside a motel was smudged to the point of illegibility by the downpour. He’d never seen anything like it. Drops as big as marbles. Monsoon rain.

He had driven down the coast, heading for the only pass through the Alps this far south. Even on full, the wipers fought to clear the water from the windscreen. The three eldest children had cocooned themselves in the back seat with pillows, sleeping bags and a woollen blanket. Lulled by the vibration of the engine and the timpani of rain on the roof, they’d quickly fallen asleep. The baby, Emma, had taken longer to settle. She was lying at his wife’s feet in a portable bed, a sort of fashionable, hippy papoose that zipped up to her chin. It had been given to them by Julia’s sister, Suzanne, as a going-away present. At the time John had believed the bed to be a waste of precious space, but it had proved surprisingly useful. Emma’s grizzling had dissolved into soft snuffling and then silence.

The map claimed they were following a highway, but to John it seemed more like a side road. There were no more towns, no street lights, not so much as a lit farmhouse window in the distance. The road eventually led them away from the coast. For miles at a time, trees grew right up to the edge of the tarseal, their branches sometimes draped with moss, all of it flashing into existence in the headlights before vanishing behind. Everything was drowning beneath the incessant rain. No headlights loomed bright in the rear mirror. No cars going north passed him.

John hadn’t seen the water on the road until the last moment. It was flowing in a broad fan at the end of a straight, along which he had unwisely accelerated. His foot jabbed at the brake and he felt the car begin to slide as he fought the drift. Wrestling the steering wheel achieved nothing; the car had its head and would not be persuaded. Still travelling fast, they left the road. The tyres bit into the narrow strip of mud and shingle at the same time as the bonnet thrust into the soft folds of the forest. By rights, they should have hit a tree and halted in a jolting mangle on the side of the road, where they would have been found in a matter of hours. Instead, the car slipped between the trunks like a blade. The only noises were the engine, the rain and the long scrape of twigs on metal. Onwards they ploughed, down a steep slope, crushing ferns and snapping saplings, to where the cliff above the river had been hidden from the road. Avoiding the last significant impediment — a granite rock as big as a washing machine — by only a few inches, the car pushed eagerly on.

Sprang.

Found the air. Where it hung.

For a fraction of a moment, the headlights shone east over the

forest. Diamonds glittered in the white light. One of the children shifted and sighed in their sleep as the windscreen wipers began their downward arc. It had all happened so quickly that John had not yet made a coherent sound.

It’s true, he thought. Everything does slow down at the end.

‘Julia.’

Pulled by the weight of the engine, the car leant forward. The headlights angled down, revealing white water and shadow boulders.

They began to fall.

When Julia finally turned her head to look at him, John could see fear filling her eyes, like water into a blue-tiled pool. He tried to reach out his hand to her. He wanted to reassure her, but moving had become too difficult. If only the seat belt didn’t press so hard across his chest. He could almost reach.

The way John said her name frightened Julia even more than the untranslatable expression on his face. Seen over his shoulder, the world outside the car was a nightmarish kaleidoscope rushing up at them. Unbidden, a prayer flashed through her mind. It was to a God she had not believed in for years, not since she was a girl. The rejected God of her mother. In a fleeting invocation — really just a wish — Julia implored someone more powerful than her to save them. Please make it that I haven’t woken up after all. Let me still be dreaming.

The car fell faster. It began to pitch and yaw.

Julia Chamberlain did not notice when her husband finally succeeded in gripping her arm. Her last thought before she died was for the baby lying at her feet.

John Chamberlain’s last thought was also about the children. He hoped they were still asleep. He didn’t want their final moments to be filled with fear. Most of all, he didn’t want them to know he had failed them.

Water rocks spinning white light

the car

fell

Almost

fe . . .

Up on the highway, the only evidence that the Chamberlains had ever been there was two smeared tyre tracks in the mud leading into the almost undamaged screen of bushes and trees. No other cars passed that way until after dawn. By that time the tracks had been washed away by the heavy rain, which, despite John Chamberlain’s prediction back in the restaurant, eased shortly before morning. It was a magic trick. After being in the country for only five days, the Chamberlain family had vanished into the air.

The date was 4 April 1978.