- Published: 9 May 2023

- ISBN: 9780143776857

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 192

- RRP: $35.00

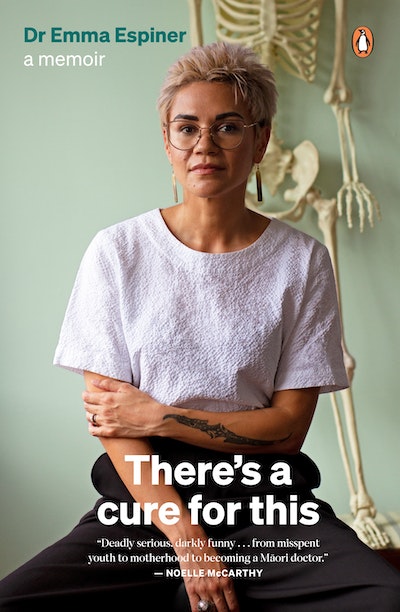

There’s a Cure for This: A Memoir

Extract

Pepeha

I wear my parents’ wedding on my arm. It might seem like an odd thing to do — getting this event memorialised in ink on my left forearm — because they have been divorced since I was three years old. But their families remain connected and, to me, the wedding itself epitomises how strong Aotearoa’s bicultural foundations can be when we meet each other in the middle.

I told my uncle Tipi Wehipeihana, a tā moko artist, that I had dreamed about my parents’ wedding the night before our appointment at his studio at Kuku Beach, almost directly opposite our marae on the other side of State Highway 1. He joined designs representing my two grandmothers with the black-and-white checks of the ceremonial tāniko cloth which covered my parents’ hands in union at a church in Tākaka long before I was born.

Mum’s family are a mix of Irish and English immigrants who arrived here with nothing and worked hard — in the mines on the West Coast, on the sea in big metal boats, on farms and in the shearing sheds. The women are fierce and the men, gentle. They love this land.

Dad’s father’s family are from Ngāti Tukorehe, nestled under the Tararua Range and linked to the sea by the Ōhau River. His mother is from Tikitiki, home to a cream weatherboard church on a hill overlooking the ocean, with crocheted pillows strewn across the pews and tukutuku panels along the walls.

Dad’s mother, Kura, is a taniwha whose tail kisses my elbow. Mum’s mother, Ethel, is a mermaid adorned with scales, journeying across the sea to Aotearoa. She begins at my wrist, a flicker starting at the gentle bump of the styloid process of my radius, fins sweeping up my arm.

The two families came together for my parents’ wedding at Pōhara, Golden Bay, the same place I married my husband nearly thirty years later. Both staunchly Catholic, each matriarch brought her own priest to the wedding, determined to ensure that only the best korowai of faith would be woven around the young couple. The photos show my grandmother Kura singing a waiata tautoko for her husband, my grandfather Martin, in front of a sea of Pākehā faces: people who didn’t understand what they were seeing but who were respectful and curious because, after all, we were becoming one family.

At my own wedding, my father-in-law — who speaks no language other than English — nonetheless got the gist of my father’s fierce whaikōrero and replied in kind, referencing his whakapapa from across the sea, his people and their land. My nieces sang his waiata tautoko — their four-piece choir trilling Bruno Mars’s ‘Just the Way You Are’ into the sea breeze.

In te ao Māori, we look backwards to the future. Drawing a permanent representation of a day when Māori and Pākehā encountered one another with love in their hearts and became a single family felt optimistic and prophetic as I sat listening to the buzz of the needle while my grandmothers appeared on my arm. These wāhine toa kept in touch for the rest of their lives, their bond long outliving my parents’ marriage. They swapped recipes and gossiped about te Hāhi Katorika, the Catholic Church, and, undoubtedly, their heathen offspring.

I graduated as a doctor in 2020 and arrived into the Covid-19 pandemic with my tā moko on my arm, my hospital lanyard, my stethoscope and a purpose. We’ve had many of our illusions about our country shattered through the circuit-breaker of this deadly pandemic. We’ve had to face up to the inequities in our society — the disparities in health, the growing numbers of unhoused people, the economic devastation of jobs lost overnight and entire sections of the economy collapsing. We’ve seen that the challenges of living in New Zealand are unevenly distributed among different groups — the ability to live well determined in part by wealth, gender, ethnicity and location. Increasingly it seems imperative that we deepen our surface-level kindness into empathy as we attempt to rebuild.

From our scattered beginnings it feels like, suddenly, we have a collective traumatic experience to draw upon, which allows us to truly see each other in a way that’s been difficult in the past. A good place to start is to look back at the journeys that brought us all to these shores, and to weave that diversity into a firm foundation for our future.

We have to draw each other close, because we are all that we have.

There’s a Cure for This: A Memoir Emma Wehipeihana (Espiner)

The striking debut memoir from award-winning doctor and writer, Emma Espiner.

Buy now