- Published: 2 November 2021

- ISBN: 9780143775553

- Imprint: Random House NZ

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 300

- RRP: $45.00

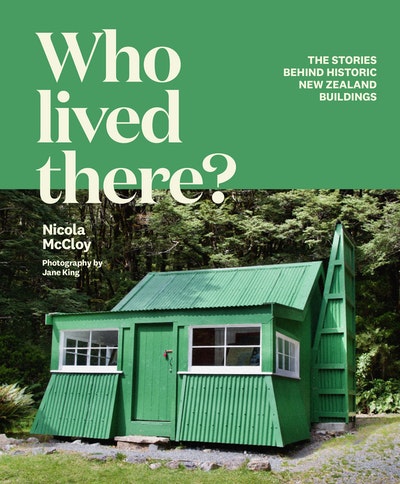

Who Lived There?

The Stories Behind Historic New Zealand Buildings

Extract

When their daughter was born, Harold and Annie Beauchamp were living at 11 Tinakori Road, close to downtown Wellington. (The road was later renumbered, so the house now stands at number 25, which meant that for some time people believed Mansfield’s birthplace had been pulled down.)

Her father had leased the land on which the house stands, off local politician Sir Charles Clifford in 1887. He agreed to a lease of 40 yearson the basis that Beauchamp build ‘a good and substantial house of the value of £400 at the least . . . with materials of the best description’.

While the house boasted five bedrooms, these were all in use when Katherine was born. Harold and Annie had two older daughters — Vera and Charlotte — and also living with the family were Annie’s two sisters, Kitty and Belle, and her mother, Margaret Dyer. Margaret spent a lot of time looking after her grandchildren, which is reflectedin Katherine’s decision to use her middle name — her grandmother’s maiden name — as her surname later in life.

When Katherine was six months old and suffering from jaundice, her grandmother took her to visit family in Anakiwa in the Marlborough Sounds, to get her out of the city. The following year, when Harold and Annie took a lengthy trip to England, it was Granny Dyer who stayed behind to look after the children.

Later in life, Mansfield wrote of her grandmother in her diary:

The only adorable thing I can imagine is for my Grandmother to put me to bed — & bring me a bowl of hot bread & milk & standing, her hands folded — the left thumb over the right —and say in her adorable voice: ‘There darling — isn’t that nice.’ Oh what a miracle of happiness that would be.

The house has been restoredto look much as it wouldhave when the Beauchampfamily lived there.

While the Beauchamps lived a relatively comfortable life in Tinakori Road, Wellington was far from being a safe city to live in. Workon a city-wide sewage system didn’t start until 1892, so cholera and typhoid were a constant concern for its citizens. This threat was not lost on Harold Beauchamp.

On 12 October 1890, he wrote to the New Zealand Times about the ‘charnel houses’ dumping waste on the seashore along the road to the Hutt Valley:

For the abominable and far-reaching stenches that greet one shortly after reaching Kaiwhara [whara], and cling tenaciously to one until Ngauranga fades from view are unparalleled in the vicinity of any town or city —Rio de Janiero, perhaps, excepted— that I have ever visited, and will, I should imagine, be just as fatal as those which are responsible for the high rate of mortality in the city I have named, unless steps are taken to remove them.

The extraordinary thing about this letter is that it was written the day after the Beauchamps’ newest daughter, Gwendoline, was born at the house in Tinakori Road.Sadly, she lived for just three months, and is buried in the nearby Bolton Street cemetery. A fifth Beauchamp sister — Jeanne — was born here two years later.

With the family continuing to grow and the economy picking up a little, the Beauchamps decided it was time to move on from the house, which Katherine later described as ‘that horrid little piggy house which was really dreadful’. In 1893, when Katherine was just five, the family moved to a more prestigious home, ‘Chesney Wold’ in Karori. The following year, another new baby — son Leslie — was born.

Mansfield wrote some of her best works, including ‘The Doll’s House’ and ‘The Garden Party’ on a Corona 3 typewriter given to her by her husband, John Middleton Murry.

Katherine had had several pieces of herwriting published in Wellington before she left for London to attend school in 1903. She returned to New Zealand at the end of 1906 but was determined not to stay long. In 1908, she returned to London to pursue her career as a writer.

Following her brother Leslie’s death at Flanders during the First World War, Katherine’s thoughts turned towards their shared childhood in Wellington. At a villain the south of France, she wrote a series of short stories that vividly describe family life in Wellington. Now considered to be some of her finest work, these stories include ‘Prelude’, ‘At the Bay’ and ‘The Garden Party’.

In ‘Prelude’, Mansfield writes of a familyin the throes of moving house. Of the empty house — thought to be based on her memories of the house on Tinakori Road, she wrote:

Slowly, she walked up the steps,and through the scullery into thekitchen. Nothing left in it but a lump of gritty yellow soap in one corner of the kitchen window-sill and a piece of flannel stained with a blue bag in another . . . she trailed through the narrow passage into the drawing-room. The Venetian blind was pulled down but not drawn close. Long pencil rays of sunlight shone down through and the wavy shadow of a bush outside danced on the golden lines.

Mansfield died of tuberculosis in France in 1923, at the age of just 34. Since then, her work has been translated into more than 20 languages and remains in print around the world. Her childhood home was purchased by the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society in 1987, and after an extensive restoration, it was opened to the public to commemorate the centenary ofher birth, in 1988.

Who Lived There? Nicola McCloy, Jane King

You can't help but wonder about the stories behind the unusual buildings you see around New Zealand - from cute colonial cottages to abandoned industrial buildings or ghost towns. Nicola McCloy went looking to find out ... who lived there?

Buy now