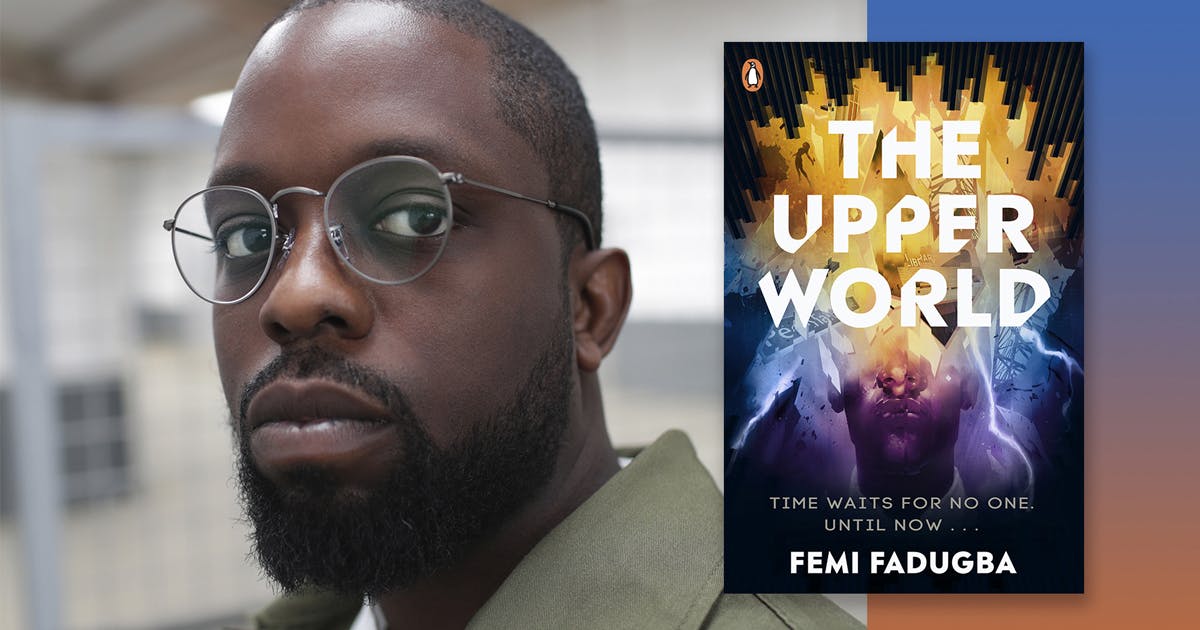

The debut author of the YA novel soon to hit Netflix on discipline, working with Daniel Kaluuya, and the complications of writing about time travel.

Femi Fadugba was working at a solar financing company when The Upper World came to him: why not merge the world of quantum physics, which he’d studied at Oxford University, with his real-world experience of growing up in Peckham? The result is a YA novel as ambitious as any, tackling themes of free will and time travel as it tells the story of Esso, who discovers his ability to see into the future and becomes preoccupied by the vision of a bullet headed his way – the very same one that, a generation into the future, is set to change young Rhia’s life, too.

And if Fadugba’s high-concept action story sounds perfect for the screen, that’s because it is: Netflix is already adapting the story, with Fadugba executive producing alongside Daniel Kaluuya.

Here, we got in touch with the debut novelist to discuss The Upper World’s inspiration, how he disciplined himself to write, and the complications of writing about time travel.

When did the idea for The Upper World first start germinating?

My job was decent and it paid the bills, but after reading about how Einstein wrote his theory of relativity while working an office job, I started to think to myself: you might not be going back into academic physics, but what are you dying to say to the world?

Once I’d picked right question, the answer came pretty quickly. Studying physics showed me from a young age that we live in a mysterious and miraculous universe (did you know there are 10,000 stars for every grain of sand on Earth?), and it’s just weird to me that no one talks about it. But I remember going out with a couple of friends one night in Peckham and them both confessing how they get into deep YouTube rabbit holes watching time travel and quantum physics videos. And in a way, that’s where the inspiration for The Upper World came from: the hunch that I could combine the everyday story of a few kids from South London with the otherworldly physics of space and time. And craft a journey gripping enough that the nerds, the mandem – and the rest of us in between – would all want to read it. And would all get it.

How did you ensure that the average reader could make sense of the quantum physics in the book?

To put it simply, physics = maths + metaphors. Maths is the language that physicists use to describe what’s going on with the world, and then we come up with clever metaphors to help us relate and understand it all. And in a weird way, fiction and stories in general provide the perfect canvas for understanding physics. After all, we’ve been creating stories for thousands of years to try and explain where we come from, where we’re going, and pretty much everything in between.

In terms of making it understandable, I think the key for any complicated concept is a) finding a way to represent what’s going on visually so people can ‘see’ it in their heads and b) attaching some serious meaning to it (in this case through the kinds of real-life events that real-life teenagers experience today). I’m still not sure what people will take from it, but I did my best to make the journey understandable and fun as well.

This is your first novel. What were the biggest challenges you faced while writing it?

I think the biggest challenge for me was wondering if what I was writing was any good. I probably asked for more feedback from people than is normal, especially early on in the project.

I mostly overcame it by including the word ‘crap’ in all my writing goals. So, for instance, I’d remind myself: ‘Your only goal is to write a crap chapter by the end of the day’, which then evolved into a bigger goal of writing a crap first draft by the end of the year. When you’re starting out writing (and honestly, at pretty much every stage that follows as well) the biggest challenge is perfectionism and the fear created by unrealistic internal and external expectations. Aiming low initially helps guard against that. Then once you actually have something to work with, you’ll find it’s not crap – and that it’s then much easier to get to good and then, hopefully, to very good.

The novel explores themes of free will. What inspired you to tackle such a big theme?

It wasn’t explicitly my intention to explore free will going in. But once you start writing any story on time travel, free will very quickly becomes the elephant in the room. In the end, I decided to focus a bit more on the psychological and sociological sides of the debate. People tend to choose one of the two camps: either the ‘I decide my own future’ team (free will) or the ‘we’re all just products of our environment’ side (determinism). I’ve always thought it was a bit of a false choice since both almost always apply at the same time.

For instance, if by some terrible stroke of luck, I was forced to fight Anthony Joshua in a packed Wembley stadium with a day to train, I’d be right to say that I’d been set up to fail. But I’m probably still going to take that one day of training seriously since, even within the terrible and narrow set of futures ahead of me, it might be the difference between me being in hospital for one week versus one year.

How did it feel when Netflix came calling to turn your work into a film?

Insane. I still haven’t processed it fully, to be honest, because it was such a sharp departure from how I’d predicted things would play out. But I’m learning to take it day by day and I’m enjoying the ride. I’m blessed and incredibly fortunate at the end of the day. Working alongside Daniel Kaluuya and Eric Newman (both co-producers) has been sick; they’re both incredibly smart, thoughtful human beings.

Have you started thinking about a second book, or a sequel?

Weirdly, the sequel to The Upper World is actually the story I would have written first if I’d had the confidence at the time. Whereas book one looks at relativity and time travel, book two is going to focus on the other (crazier) branch of physics: quantum mechanics and the multiverse. I’ve spent a lot more time in quantum stuff, so the worldbuilding has come more naturally. I’m also getting to reach into the history of my main characters and their families, which recently took me and my wife on a crazy research trip to Cotonou, Benin. I’m deep in the writing and the big question I keep asking is: Do I go bold? Or do I play it safe given I now know what worked last time? I think I’ve got to go bold.

Photo: Ernest Simons