Read the story being discussed onJesse Mulligan’s show on Radio New Zealand on 7 September 2017

The Seahorse and the Reef

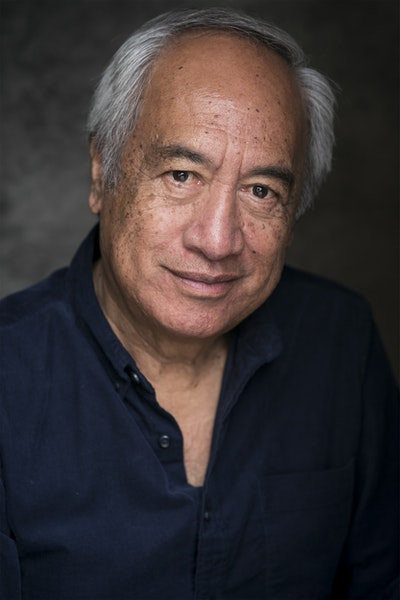

by Witi Ihimaera

Sometimes through the soft green water and drifting seaweed of my dreams I see the seahorse again. Delicate and fragile it comes to me, shimmering and luminous with light. And I remember the reef.

The reef was just outside the town where my family lived. That was a long time ago, when I was a boy, before I came to this southern city. It was where all our relatives and friends went every weekend in summer to dive for kai moana. The reef was the home of much kai moana — paua, pipi, kina, mussels, pupu and many other shellfish. It was the home too of other fish like flounder and octopus. It teemed with life and food. It gave its bounty to us. It was good to us.

And it was where the seahorse lived.

At the time, our family lived in a small wooden house on the fringe of the industrial area. On Sundays, my father would watch out the window and see our relatives passing by on their old trucks and cars and bikes with their sugarbags and nets, their flippers and goggles, shouting and waving on their way to the reef. They came from the pa — in those days it was not surrounded by expanding suburbia — and they would sing out to Dad:

‘Hey, Rongo! Come on! Good day for kai moana today!’

Dad would sigh and start to moan and fidget. The lunch dishes had to be washed, the lawn had to be cut, and my mother probably would want him to do other things round the house.

But after a while, a gleam would come into his eyes.

‘Hey, Huia!’ he would shout to Mum. ‘Those kina are calling out loud to me today!’

‘So are the dishes,’ she would answer.

‘Well, Mum!’ Dad would call again. ‘Those paua are just waiting for me to come to them today!’

‘That lawn’s been waiting even longer,’ Mum would answer.

Dad would pretend not to hear her. ‘Pae kare, dear! How’d you like a feed of mussels today!’

‘I’d like it better if you fixed the fence,’ she would growl.

So Dad would just wiggle his toes and act sad for her. ‘Okay, Huia. But those pipi are going to miss us today!’

Dad was cunning. He knew Mum loved her feed of pipi. And sure enough she would answer him:

‘What are we waiting for? Can’t disappoint those pipi today!’ Then she would shout to us to get into our bathing clothes, grab some sugarbags, don’t forget some knives and take your time but hurry up! And off we would go to the reef on our truck.

If it was a sunny day the reef would already be crowded with other people searching for kai moana. There they’d be, dotting the water with their sacks and flax kits. They would wave and shout to us and we would hurry to join them, pulling on our shoes, grabbing our sugarbags and running down to the sea.

‘Don’t you kids come too far out!’ Dad would yell. He would already be way ahead of us, sack clutched in one hand and a knife in the other. He used the knife to prise the paua from the reef because if you weren’t quick enough they held onto the rocks really tight.

Sometimes, Dad would put on a diving mask. It made it easier for him to see underwater.

As for Mum, she liked nothing better than to wade out to where some of the women of the pa were gathered. Then she could korero with them while she was looking for seafood. All the long afternoon those women would bend to the task, their dresses ballooning above the water, and talk and talk and talk and talk!

For both Mum and Dad, much of the fun of going to the reef was because they could be with their friends and whanau. It was a good time for being family again and for enjoying our tribal ways.

My sisters and me, we made straight for a special place on the reef that we liked to call ‘ours’. It was where the pupu — or winkles as some call them — crawled. We called the special place our pupu pool.

The pool was very long but not very deep. Just as well because Mere, my youngest sister then, would have been drowned, she was so short! As for me, the water only came waist high. The rock surrounding the pool was fringed with long waving seaweed. Small transparent fish swam among the waving leaves and little crabs scurried across the dark floor. The many pupu glided calmly along the sides of the pool. Once, a starfish inched its way into a dark crack.

It was in that pool we discovered the seahorse, magical and serene, shimmering among the red kelp and riding the swirls of the sea’s current.

My sisters and I, we wanted to take it home.

‘If you take it from the sea it will die,’ Dad told us. ‘Leave it here in its own home for the sea gives it life and beauty.’

Dad told us that we must always treat the sea with love, with aroha. ‘Kids, you must take from the sea only the kai you need and only the amount you need to please your bellies. If you take more, then it is waste. There is no need to waste the food of the sea. Best to leave it there for when you need it next time. The sea is good to us, it gives us kai moana to eat. It is a food basket. As long as we respect it, it will continue to feed us. If, in your search for shellfish, you lift a stone from its lap, return the stone to where it was. Try not to break pieces of the reef for it is the home of many kai moana. And do not leave litter behind you when you leave the sea.’ Dad taught us to respect the sea and to have reverence for the life contained in its waters. As we collected shellfish we would remember his words. Whenever we saw the seahorse shimmering behind a curtain of kelp, we felt glad we’d left it in the pool to continue to delight us.

As soon as we filled our sugarbags we would return to the beach. We played together with other kids while waiting for our parents to return from the outer reef. One by one they would arrive: the women still talking, the men carrying their sacks over their shoulders. On the beach we would laugh and talk and share the kai moana between different families. With sharing there was little waste. We would be happy with each other unless a stranger intervened with his camera or curious amusement. Then we would say goodbye to one another while the sea whispered and gently surged into the coming of darkness.

‘See you next week,’ we would say.

One weekend we went again to the reef. We were in a happy mood. The sun was shining and skipping its beams like bright stones across the water.

But when we arrived at the beach the sea was empty of the family. No people dotted the reef with their sacks. No calls of welcome drifted across the rippling waves.

Dad frowned. He looked ahead to where our friends and whanau were clustered in a large group on the sand. All of them were looking to the reef, their faces etched by the sun with impassiveness.

‘Something’s wrong,’ Dad said. He stopped the truck. We walked with him towards the others of our people. They were silent. ‘The water too cold?’ Dad tried to joke.

Nobody answered him. ‘Is there a shark out there?’ Dad asked again.

Again there was silence. Then someone pointed to a sign.

‘It must have been put up last night,’ a man told Dad.

Dad elbowed his way through the crowd to read it.

‘Dad, what does it say?’ I asked.

His fists were clenched and his eyes were angry. He said one word, explosive and shattering the silence, disturbing the gulls to scream and clatter about us.

‘Rongo,’ Mum reproved him.

‘First the land and now our food,’ Dad said to her.

‘What does it say?’ I asked again.

His fists unclenched and his eyes became sad. ‘It says that it is dangerous to take seafood from the reef, son.’

‘Why, Dad?’

‘The sea is polluted, son. If we eat the seafood, we may get sick.’

My sisters and I were silent for a while. ‘No more pupu, Dad?’

‘No more, kids.’

I clutched his arm frantically. ‘And the seahorse, Dad? The seahorse, will it be all right?’

But he did not seem to hear me.

We walked back to the truck. Behind us, an old woman began to cry out a tangi to the reef. It was a very sad song for such a beautiful day. ‘Aue … Aue …’

With the rest of the iwi, we bowed our heads. While she was singing, the sea boiled yellow with effluent issuing from a pipe in the seabed. The stain curled like fingers around the reef.

Then the song was finished. Dad looked out to the reef and called to it in a clear voice.

‘Sea, we have been unkind to you. We have poisoned the land and now we feed our poison into your waters. We have lost our aroha for you and our respect for your life. Forgive us, friend.’

He started the truck. We turned homeward.

In my mind I caught a sudden vision of many pupu crawling among polluted rocks. I saw a starfish encrusted with ugliness.

And flashing through dead waving seaweed was a beautiful seahorse, fragile and dream-like, searching frantically for clean and crystal waters.