Liam Pieper’s The Toymaker asks people to speak up when it matters.

Bold, dark and compelling, Liam Pieper’s The Toymaker is a novel about privilege, fear and the great harm we can do when we are afraid of losing what we hold dear. Here Liam offers some insights into the places, people and events that helped him shape this unflinching examination of society…

The Toymaker is an idea that’s been rattling around in my subconscious since I was a child. Growing up, most of my friends were the grandchildren of Jewish émigrés from Eastern Europe, and I was very aware of the things their grandparents had suffered. I was always a little awed by the idea that these people could endure the evils of the Holocaust, and then just try to start again in a country that was, for the most part, indifferent to your suffering, that had watched it happen and hadn’t tried to stop it until way too late.

Arkady Kulakov, or at least the person he pretends to be, is a composite of several wise, gentle men I knew growing up. In Europe they had been going about living their lives, and suddenly the world went mad around them, and they lost everything. There was a certain sadness to them, and also a secrecy – they had seen things no human should, done things to survive they would never tell anyone.

I struggled for a long time with the ethics of writing about the Holocaust. The last thing I wanted was to be exploitative of past horrors, or to disrespect the memory of the millions of victims or the legacy of the survivors. It is a cheap shot from all sides of politics to compare the elements of your society that make you uncomfortable with the Nazis.

However, I’ve been watching, ever since the Tampa affair, my own country become increasingly hostile to the suffering of others, long past the point of indifference. As a novelist my intent is not to be political, but I do have a duty to be compassionate, and I worry that a government can get a boost in the polls by treating abused and scared refugees to state-sanctioned cruelty. A nation can be judged by how it treats those from outside who need its help. It’s worth remembering that the USA turned down Anne Frank’s request for asylum. It’s worth remembering how much we forget when it’s convenient to us.

This book was written in bits and pieces across four years, a large part of it in India, where President Modi was orchestrating one of the furthest-right governments India has ever seen. This is a guy who has used race riots for political gain, so the whole time I was there, all my friends had this creeping sense of dread about the direction of society. In towns not far from us, books were being burned. A novelist friend of mine was harassed by a far-right group until he quit writing altogether and went into hiding to save his family.

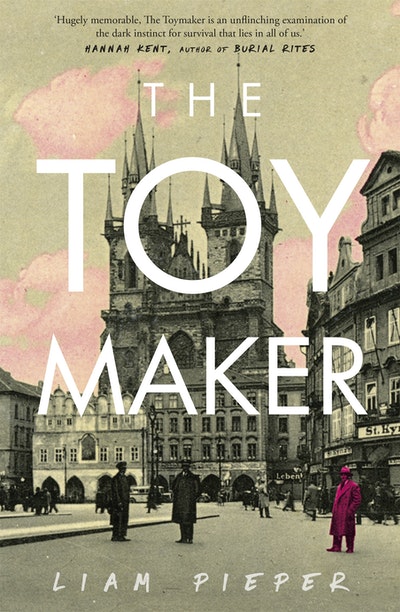

It only really started to take its final shape, though, when I was lucky enough to be invited by UNESCO to come and finish it in Europe as the inaugural creative resident of The City of Literature Prague.

It’s impossible to over-emphasise how important this opportunity was to writing The Toymaker. I’d been researching the story my whole life, but it’s a whole different thing to be able to walk the streets I was writing about, to go to Auschwitz, to talk to survivors. While all this was going on, I was in Europe in the middle of the Syrian refugee crisis, and I was watching Europe grow more right-wing by the day. They were stopping international buses and checking everybody’s ID, questioning all the brown people. When I was in Krakow to research, a mob burned an effigy of a Jew in the middle of town. It was strange and surreal.

But Prague is where The Toymaker took its final shape, when all these disparate threads started to crystallise in my mind. I went to Bubny station, which is where all of Prague’s Jews boarded trains to be taken to their deaths, amongst, them, incidentally, Kafka’s family. It’s just an ordinary station, still functioning, with commuter trains rolling through it all day. It was the same on the day of the genocide. Everybody just went to work, and ignored what was happening.

There’s a monument there now, the only sign of what happened. The railway tracks the trains to Auschwitz left on have been rerouted and head up towards the sky, to heaven. It’s very striking. The idea is that people on the way to work will see this thing, this railway to the sky which looks fundamentally wrong, and ask what it is, and think about it – the way they didn’t back in 1942. If enough of those commuters had spoken up, things would have been very different. Silence is deadly.

This book is my answer to that monument. I see what is happening in the world right now, and it terrifies me that too few people are thinking about it. This is my attempt at getting people to think about where their society is going, not to be silent about it.