- Published: 2 July 2021

- ISBN: 9780143775980

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $35.00

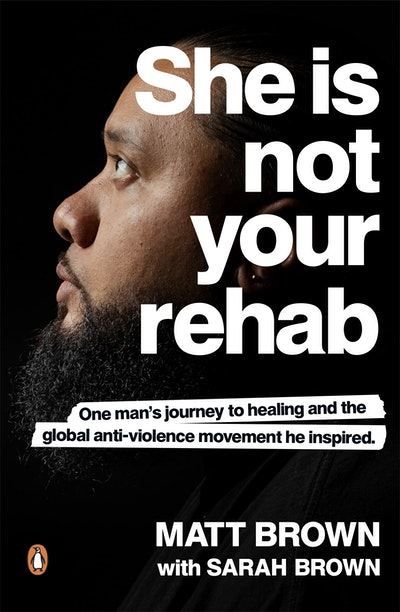

She Is Not Your Rehab

One Man’s Journey to Healing and the Global Anti-Violence Movement He Inspired

Extract

– at least weekly – but often the cycle of physical violence andemotional abuse was a daily occurrence, so that it seemed like an endless experience for us all.

We had an ‘open home’, which meant all kinds of people wouldcome in and out of our house constantly, and that resulted inmultiple incidents of sexual abuse by relatives and associates.

My love of art and music was my refuge. The nineties hip-hop scene, and Tupac Shakur in particular, gave me an outlet that I connected deeply with. The music room at my high school became my safe space, and my music teacher let me hide out there after school, so I could temporarily delay going home and having to face what was happening there.

Home for me never ever felt safe.

My love of art and music was my refuge. The nineties hip-hop scene, and Tupac Shakur in particular, gave me an outlet that I connected deeply with. The music room at my high school became my safe space, and my music teacher let me hide out there after school, so I could temporarily delay going home and having to face what was happening there.

‘Being a barber, I have come to understand the extraordinary gift my job is, and the power I have to challenge an often-negative narrative that society has about men.’

It was also music that brought my wife Sarah into my life, but you’ll find out more about our journey of awakening to love together throughout this book, because our story has made me understand how relationships can either help or hinder your healing. How, at the end of the day, each one of us needs to sort our own shit out!

I’ve been a barber now for over a decade. Because of my history, when I first started my barbershop I wanted it to be more than just a barbershop. Prior to being a barber, I was a joiner by trade. Then one day I woke up and decided that a hobby I’d had since high school – barbering – could actually be a job, and away I could connect with the men in my neighbourhood. The reality was no one was coming for us. So yes, I wanted to give dope fades, like those of the hip-hop stars I so admired, but I also wanted my barbershop to be more of a place where men could be seen.

I wanted to connect on a deeper level with guys I knew from the hood, guys I had grown up with. I knew first-hand the power of a haircut – and how it could change the way we feel about ourselves inside. I thought if I could combine a great haircut with a listening ear, then maybe something special could happen.

So many of the guys in my neighbourhood had gone downpaths of joining gangs, becoming incarcerated or addicted, with some even tragically ending their lives. I saw pain all across my community.

And I knew why. The sad truth is that while many of us were now out in the real world, we were still traumatised from the childhoods we had barely survived, and were coping however we could. Their stories were my stories, and my stories were theirs.

It was our pain that made us a family. Inside my very first tinshed barbershop, which I started in my backyard, we’d laugh together about the hidings we got as kids, or how our Mothers would gamble away the food money on Thursdays, or how many times our Fathers had been inside prison. It wasn’t funny at all, but somehow these conversations kept us all from not feeling alone in our pain.

Shared pain somehow feels less traumatic.

I could call these men my first clients, but, really, they becameso much more. They were my friends, my Brothers, my teachers – more than that, they were my insight into humanity.

I started to spend my days, and many nights, talking to the men in my city. They were all ages, and from all walks of life.We talked about their deeper pain, their untold stories, and the things they regretted or wanted to change. So funnily enough it was in that barbershop – with me mostly looking at the back of their heads – where they felt the most seen, they told me.

Those early conversations were special, and I’ll never forget the very first time, after deeply connecting with a client who was experiencing suicidal thoughts, when I thought: ‘This is it! My job here, in my garden-shed barbershop in the hood, could make an actual difference in people’s lives!’ This moment forever changed my barbering career, because every day, as I’m cleaning my tools and getting ready for my day, I know, without doubt, that I can make a difference by genuinely seeing and hearing the men who sit in my chair.

The truth is there are ways we can all impact our communities,and become part of changing a culture in positive ways to universally raise consciousness. We can each redefine what ‘traditional masculinity’ looks like in whatever job we do. Being a barber, I have come to understand the extraordinary gift my job comes with, and the power I have to challenge an often-negativenarrative that society has about men.

Not many people are allowed into another man’s personal space quite like a barber is, and for that reason I consider the work I do as sacred. Barbering, to me, is an authentic journey of men. It’s learning to accept a man exactly as he comes to me in my chair, and serving him without judgement. Only then can I see the beauty in the men hiding behind the masks that, often, they have nowhere else to remove.

In this book, I will introduce you to the people and the concepts that have helped me on my own journey of healing. These ideas may work for you, or they may not, but I invite you to begin your journey of healing now. There is never a better time than now,and if you ever needed one, this is your invitation. What you read here may spark ideas that take you on a completely different path to mine, and that’s okay, as long as you’re willing to take responsibility for your own feelings and actions. I don’t believe in a ‘one size fits all’ approach to healing, because we are each so unique in our experiences and personalities that the path for each of us will inevitably be as varied as we are.

She Is Not Your Rehab Matt Brown

Cycles repeat until one person has the courage to say, ‘This stops with me.’

Buy now