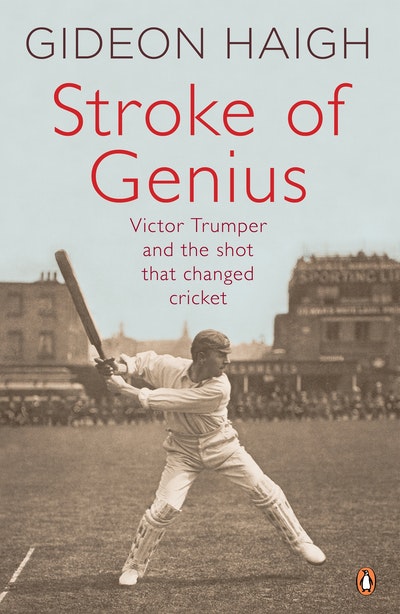

Gideon Haigh’s Stroke of Genius tells the extraordinary story of how one player – and his photograph – changed a sport and a nation.

Today Australian cricketer Victor Trumper is revered for deeds lost in time, a hallowed name from the golden era from before the moving image began to dictate memories and Bradman reset the records. In life, Trumper was Australia’s first world beater – at his peak just after Federation, he was not just a cricketer but an artist of the bat, the genius of a new era, a symbol of what Australia could be. Crowds flocked to his club matches, English supporters cheered him on in Tests, and at his early funeral in 1915 – even amidst the grief of war – mourners choked the streets of Sydney.

Trumper lives on in an image captured by George Beldam – the batsman mid-stroke: a daring player’s graceful advance into the unknown, alive with intent and controlled abandon. The photograph has become an icon. And as a celebration of this, in Stroke of Genius Haigh reveals how Trumper, and Beldam’s incarnation of his brilliance, are at the intersection of sport and art, history and timelessness, reality and myth.

Among the compelling historical notes, Haigh also draws attention to the visual documentation of nineteenth century Indigenous Australian cricketers – images surprisingly profuse, given the small numbers of Indigenous players. ‘…That, perhaps, is the point,’ offers Haigh, ‘by making a record, by providing “proof”, those responsible could demonstrate progress, fire enthusiasm.’ Yet, he adds, the scenes captured can be ambiguous, hardly evidence of the flourishing relationships between Indigenous and white Australians.

From the pages of Stroke of Genius, here Haigh brings to life the details surrounding this remarkable photograph taken at the MCG in 1866.

Images were integral to the best known of all Indigenous cricket strivings – the talented team hailing from Victoria’s Western District, whose journey from Edenhope to England made them the first Australian cricket tourists, a decade in advance of an official team. The team’s station-owner organisers, William Hayman of Lake Wallace and Thomas Hamilton of Bringalbert, substantiated their application for a match with the Melbourne Cricket Club by sending a handsome set of studio photographs of the team members, dignified and resplendent in their whites, taken by J. C. A. Kruger of Warrnambool in March 1866. By the time these photographs were used as the basis of a promotional engraving by Samuel Calvert in the Australian News nine months later, one of the players, Sugar, had actually died. But he rejoined his comrades one last time around a set of stumps beneath an imagined pennant for the ‘A. C. C.’ – the Aboriginal Cricket Club, perhaps.

Ahead of their Boxing Day fixture, the team sat for a real team photograph, since widely reproduced, encased this time in jackets and waistcoats, white pot hats doffed. To the left stands King Cole, leg propped on a chair, elbow resting on a knee, almost parodic of the leisured gent. In the back row stands the coach provided by the club, Tom Wills, left hand at his breast, perhaps a touch uncomfortably, for this coming-together is as artificial as it is hopeful. ‘These men are literally and truly the last of their race,’ Hayman prophesied confidently in The Australasian, ‘and in a few years the aboriginals [sic] will have ceased to exist in the West Wimmera district.’ The first plan to mount an Aboriginal tour of England fell foul of a con man. The second was regarded with deep suspicion by the Central Protection Board. They made their way in England by playing up to the exoticism of a second team photograph, taken by Warrnambool’s Patrick Dawson, featuring half the members with bats and balls, the other half with hunting implements: their games were punctuated by displays of athletic prowess and tribal skills featuring traditional weapons, some of them left behind at Lord’s and Exeter’s Royal Albert Memorial Museum. Also left behind, in Victoria Park Cemetery, were the mortal remains of King Cole, he of the languid stance, after his death from tuberculosis in Guy’s Hospital.