- Published: 3 November 2014

- ISBN: 9781864712780

- Imprint: Bantam Australia

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 496

- RRP: $28.00

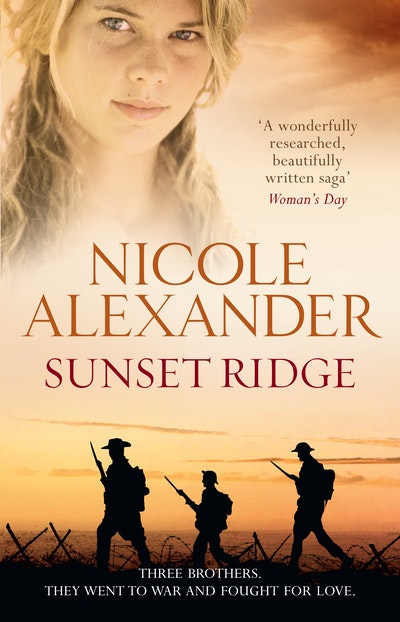

Sunset Ridge

Extract

At seventy, Jude Harrow-Boyne was the poster child for most women her age. Athletic and youthful, she was intelligent if somewhat scatty at times. Known equally for her ?erce temper and artistic ability, Jude had an almost complete disregard for other people’s opinions, a personality ?aw that was dif?cult to take at times. With this knowledge in mind, Madeleine knew that her brief stay with her mother in Brisbane would not go well, which was why she had arrived at the ground-?oor apartment the previous day with two bottles of white wine and a bunch of ?owers. Neither gift made a dent in Jude’s attitude; if anything, the peace offerings were treated with suspicion. Her mother was expecting positive news and Madeleine had none to give.

The rental car charged up each rolling ridge, a hazy mirage of dirt and sky enticing Madeleine onwards. Nondescript trees blurred the edges of the road as a trickle of sweat rolled down her back. She could feel the sun burning her face and arms through the window and her eyes were smeary from the glare. About an hour earlier she had considered pulling up under a tree to try to sleep. However, the temptation to rest had been tempered by the heat. Madeleine scrabbled on the passenger seat for the last water bottle. She shook it for any remaining drops, then tossed it over her shoulder onto the back seat and ?ddled with the air-conditioning in an attempt to force air into the vehicle. The more kilometres travelled the less enthusiastic she became. This journey had come at the instigation of her mother some months ago, and in spite of the lecture received last night Madeleine felt instinctively that this visit to the Harrow family property would be a waste of time. By agreeing to undertake the trip, an olive branch had been extended, though a few of the leaves were already bruised.

Eighteen months ago her mother had approached Madeleine with the suggestion of staging a retrospective of her late grandfather’s work. An artist of renown, David Harrow had died well before Madeleine and her older brother George were born, and even Jude admitted that between boarding school and art college she had barely known her widowed father. It was with a great degree of reluctance that Madeleine, in her role as personal assistant to the director of the Stepworth Gallery, agreed to investigate the feasibility of the project. There were professional reasons for her hesitancy as well as a number of personal ones.

David Harrow had died in the early 1950s, bequeathing to his only daughter a debt-ridden rural property that had been in the family for generations – absurdly named Sunset Ridge – and forty landscape paintings. The paintings were found stored within the Sunset Ridge homestead, and when auctioned at an estate sale they had created quite a buzz in the art world. The hitherto unknown artist had emerged posthumously to acclaim, and his collective works were touted as one of the great ?nds in Australian art history.

From Madeleine’s perspective, however, his legacy had been lost, sold by her parents more than forty-?ve years ago to restore the Harrow family property to viability. To Madeleine, such an action made Jude’s ongoing devotional attitude towards her father almost hypocritical. And Madeleine couldn’t help but feel both annoyed by and disinclined to support Jude’s idea of a retrospective. If her mother cared so much about her father and his art, why sell it all? The closest Madeleine ever got to her grandfather was through the study of his painting techniques as part of the university syllabus while completing her Fine Arts degree or when Jude paraded the original 1950s art catalogue on each anniversary of his death. Meanwhile Madeleine’s brother George lived out here in the back of beyond on the family farm, which she and her mother rarely visited.

After seven hours in the car she was starting to remember why.

Madeleine missed the turn-off to Sunset Ridge by a good two kilometres. On retracing her route she saw that the signpost had been removed from the opposite side of the road and that the battered ramp and the old fridge once used as the mailbox had been replaced with a white boundary gate and matching mailbox upon which ‘Sunset Ridge’ was painted in black. It was a much-needed improvement, she thought as she accelerated through the open gate. She guessed that the temperature outside had hit forty degrees. What constituted a heatwave across much of Australia was merely another day in this part of the world. The thought of spending two weeks lying awake night after night with the sweat streaming from her body was disheartening. Changing down through the gears to drive over a stock grid, Madeleine relived last night’s fractious discussion with her mother.

‘You’re the assistant to the gallery director, Madeleine, and your grandfather was a brilliant artist – and you’re telling me it hasn’t even been discussed yet? You said you would table it at the board meeting months ago.’ Jude slid a menthol cigarette out of its soft packet, dried paint rimming her fingernails.

‘Well, I did say it would be difficult, Mum,’ Madeleine argued. ‘I have to present a clear and compelling case to show why Grandfather deserves a retrospective, without opening myself up to accusations of bias. Remember, Mum, I’m championing a man I never knew, and I have limited archival material to work with.’

‘But we have the forty paintings!’ Jude retorted. ‘Most of the owners have said they will lend their works, haven’t they? And we have a couple of his early sketches.’

‘Yes, Mum, but a good retrospective should include details of the artist’s life, early drawings, personal correspondence: a timeline of his life and the influences on his work.’

Jude looked away dismissively and tapped ash into a garish pink-and-red ceramic dish. ‘Father’s work is good enough without having all that extra information.’ She returned her gaze to her daughter. ‘And if you really think you need all that other material to make the exhibition more interesting, then why haven’t you been more proactive? Why haven’t you found it?’ Jude picked up her wine glass and studied the watercolour of frangipanis sitting on the easel in the middle of the cluttered living room. Her current work-in-progress was a commission of eight paintings for a riverside restaurant.

‘The gallery is a business, Mum. It’s all about the bottom line. Besides, Australiana isn’t the in thing at the moment; everyone is more interested in contemporary and indigenous art.’

‘Don’t sit there and give me your economic arguments, Madeleine Harrow. I wasn’t the one who changed my name by deed poll. Your father, bless him, graced us with the surname of Boyne. You didn’t mind using your connection to your grandfather to wangle yourself into a gallery career. The least you can do is honour the name and the man. David Harrow deserves an exhibition, and you know it.’

Madeleine fidgeted with the silk sari covering the armchair. ‘But I don’t know enough. I didn’t know him. Did he paint his lovers like Picasso did? Did he have a muse? Why did he become so reclusive after returning from the First World War?’

Jude took a sip of wine before sitting the glass on the messy coffee table. ‘And,’ she said defiantly as she flipped open a large sketchpad and removed a sheet of paper, ‘why did he not accept his platoon captain’s recommendation to be put forward as an official war artist?’ She thrust the letter towards Madeleine. ‘It’s from the Australian War Memorial. Captain Egan thought your grandfather was talented enough to sketch on behalf of us all.’

Madeleine scanned the contents, speechless.

‘Well, you said you needed archival material.’ Jude passed her daughter a photocopy of a sketch. ‘The young man in this portrait is Private Matty Cartwright. Your grandfather sketched this a week before Cartwright was killed by a shell in Belgium in 1917. The original was returned to the Cartwright family with the rest of his personal effects, and it was eventually bequeathed to the War Memorial.’

Madeleine stared at the drawing of the young man.

‘There are three more similar sketches,’ Jude continued. ‘Only one bears my father’s initials; however, the art historian attached to the War Memorial seemed convinced that the works could be attributed to your grandfather.’ Jude gave a satisfied smile. ‘You can close your mouth, dear.’

‘This is –’

‘Extraordinary? Yes it is. Consider the providence of that drawing, Madeleine: where and when it was sketched, and by whom. Now look closely at the work. It’s damn good.’

Jude turned towards the two charcoal sketches hanging on the wall behind her. Both drawings depicted four young men fishing by the Banyan River and displayed all the hallmarks of raw talent. ‘It’s amazing what you can discover once you start looking,’ her mother said pointedly. ‘I can only assume that you don’t think your grandfather is good enough to warrant a retrospective.’

‘I never said that.’

‘Then perhaps it would be easier if you stopped thinking like a businesswoman and started behaving like a granddaughter. I am well aware that there are few historical documents available to us, however even you can’t dispute the importance of those First World War sketches. In the early stages of his career Father appears to have been ambivalent towards his talent. He doesn’t seem to have made notes or kept rough outlines of works-in-progress, and we know he didn’t always sign his drawings, which makes your sourcing of them extremely difficult. There isn’t even a single sketchbook to be found.’ Jude turned back to her daughter. ‘What intrigues me is the gap in his work. We have sketches from the war and then nothing until the first landscape dated 1935. Are there more paintings from this lost period or did he simply stop creating, and if so why?’ Jude lit another cigarette, inhaling deeply. ‘At least we now have something to work with, a starting point.’

Madeleine reluctantly agreed.

‘We’ve had our differences, Maddy. I guess all mothers and daughters do at times, and I am well aware that you believe I did the wrong thing selling your grandfather’s paintings all those years ago. And maybe I did. But, Maddy, please don’t allow your ill feeling to hinder the chances of staging this retrospective. What if there are more of his drawings?’ She pointed at the sketch Madeleine still held. ‘More sketches from the war, more works drawn before he enlisted.

Do you honestly believe he just woke up one morning and decided to paint forty masterpieces in the last twenty-five years of his life?’

‘Well, I –’

‘Who knows what other pieces could be floating around the world? Who knows how many sketches and paintings sit hidden in attics, hang unheralded on walls, or for that matter were buried in the mud of the Somme? This is your family history too, Maddy, and I’m asking you to use your contacts and your knowledge to make this retrospective happen. I wanted you to be involved not only because you’re his granddaughter and understand the art world, but also because we both know that you would benefit professionally if the retrospective goes ahead. But if you keep delaying it I will have no choice but to hand it over to somebody else.’ Jude took the sketch from Madeleine and slipped it between the pages of the sketchpad. ‘In the end, the retrospective is about honouring a great man, not you and me arguing over our differences.’

Madeleine had never liked ultimatums, and she made a point of telling her mother just that. She had, after all, agreed to visit Sunset Ridge with a view to soaking up the environment that inspired her grandfather, yet still Jude couldn’t help but lecture her. Last night’s conversation had quickly degenerated, leaving Jude to retreat to her bedroom with a bottle of wine, while Madeleine fell asleep on the couch. The high point of the evening was when Jude handed Madeleine a rusty key and tersely informed her that it belonged to a tin trunk in the Sunset Ridge schoolroom – a trunk containing items that had belonged to Madeleine’s father, Ashley, and had not been touched since his death twenty years earlier. George’s wife, Rachael, was intent on clearing out the schoolroom and Jude wanted Madeleine to sort through and dispose of the items in the trunk. ‘I don’t want Rachael touching those things,’ Jude had said stif?y. ‘It’s a family matter.’

The car rattled over the corrugations in the road. The ?nal few kilometres were punctuated by stockless paddocks and desolate cultivations. The drought was biting hard across eastern Australia but apparently George was still managing. The road to the homestead veered through red ridges and uninviting stubby scrub that merged with dry-leafed trees. George’s wish of thinning out the dense bushland had not eventuated. Instead, the money was put towards pushing saplings in a far paddock for sheep feed. The result was a narrow track that seemed at constant battle with the scrub lining either side. The rental car bumped over the rough road, wound past a fallen-down crutching shed and hit the straight track and open gateway that led to the homestead. The sixty-acre house block had been systematically cleared a hundred years ago, and the area remained virtually treeless except for three stands of Box trees that sat halfway between the work shed, stables and house dam. Beyond the house paddock to the south-east was a shearing shed and the Banyan River, which had been dry for nearly two years.

Sunset Ridge Nicole Alexander

From Nicole Alexander, the 'heart of Australian storytelling', comes an epic historical novel that takes three brothers from the drought-stricken outback of Queensland to the horror of the trenches in World War One.

Buy now