- Published: 5 July 2022

- ISBN: 9781760890094

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 368

- RRP: $37.00

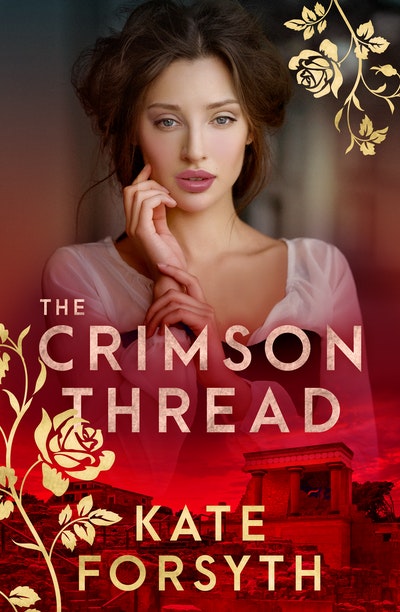

The Crimson Thread

Extract

25 April 1941

‘Red thread bound,

in the spinning wheel round,

kick the wheel and let it spin,

so the tale can begin.’

Alenka’s grandmother chanted those words to her every night as she told her a story, sewing as she spoke, each stitch as tiny as if set by a fairy.

Yia-Yia knew many stories of gods and heroes, giants and nymphs, and the Three Fates who spun and measured and cut the thread of life. Many of Yia-Yia’s tales were strange and terrible. A girl who was turned into a tree. A woman cursed with snakes for hair. Another whose tongue was cut out and who could only tell her story by embroidering it upon a cloth. The story Yia-Yia told most often, though, was that of the minotaur in the labyrinth, for it was the mythos of Alenka’s home, the ruins of the palace of Knossos in the island of Crete.

Once, a long time ago, her grandmother would say, a princess lived here. Her name was Ariadne, and she was the mistress of the labyrinth, for she held the key to the puzzle of paths where the minotaur was hidden. Half-man, half-bull, the minotaur was fed every seven years on the blood of seven young men and seven maidens. One day a hero named Theseus came, determined to defeat the monster, and Ariadne showed him the way into the labyrinth and gave him a sword and a spool of blood-red thread so he could find his way out again.

‘Is it true, Yia-Yia?’ Alenka once asked. ‘Did a monster really once live here?’

Yia-Yia had smiled, sighed, shrugged. ‘Po-po-po, who knows? Lies and truths, that is how tales are. Perhaps there was no minotaur. Perhaps bulls were sacred to the people who once lived here, and that is why they painted or sculpted them so often. Maybe it was just a sport, like bullfighting, young men and women risking their lives to leap over the bull’s horns. Maybe all of it is true, or maybe none of it. Now close your eyes and go to sleep.’

Alenka liked to think it was true. One of her greatest treasures was an ancient coin she had found in the ruins, with a labyrinth of seven circuits engraved upon one side and a woman’s crowned head on the other. She wore the coin hanging around her neck with a little golden cross and a blue bead, a charm against the evil eye her godparents had given her at her christening.

Every year, in early spring, Alenka’s grandmother had woven together red and white thread to make her a martis bracelet, a talisman against harm. Alenka would wear it about her wrist until the almond tree in the village square began to blossom and the first swallow swooped in the sky. Then she and the other villagers would tie their bracelets to a branch of the tree to encourage a good harvest that year.

But Yia-Yia had died that winter, so Alenka had to weave her own martis bracelet. It seemed the magic had failed with her grandmother’s death. The coming of spring brought terrible danger. The German army was marching down the flanks of Mount Olympus towards Athens. Soon, Greece would fall to the Nazis, as every other country had done. Only the British fought valiantly on.

It was hard not to lose hope. Why, the King of the Hellenes had already fled. He was here in Crete, at the Ariadne Villa in Knossos, along with Emmanouil Tsouderos, the newly appointed prime minister. His predecessor had shot himself just a week earlier. The official report said he had died of a heart attack, but everyone knew that was a lie.

Alenka worked as a translator and guide for the curator of the archaeological dig at Knossos. He lived in a small cottage in the garden of the villa, which had been built by Sir Arthur Evans, the British archaeologist who had discovered the ruins of the ancient palace. Alenka’s mother was the housekeeper at the villa, so Alenka had grown up playing in the ruins, listening to the stories of the archaeologists, and typing up their articles and books. It was her dream, though, to go to Oxford and study history and languages. In her secret heart, she wanted to solve the riddle of the ancient hieroglyphs found on Crete. No-one had ever been able to crack the code, though an Australian classicist named Florence Stawell had come close. Alenka had been studying hard for her university entrance exams, but the war had changed everything.

She sighed. Carefully she set a stitch in the white linen of her sindoni, the embroidered sheet that would be pinned to her wedding quilt, as if that act of needlework would keep her family safe against the coming danger. Alenka was sewing a constellation of seven red knots above the dancing figures of a boy and a girl and their mother. Her family.

As she sewed, she silently chanted the charm her grandmother had taught her:

By knot of one, the spell’s begun.

By knot of two, it cometh true.

By knot of three, make it be.

By knot of four, this power I store.

By knot of five, the spell’s alive.

By knot of six, this spell I fix

By knot of seven, angel of heaven.

She snipped the red thread with her stork-shaped scissors, muttering a familiar prayer, ‘O holy angel, deliver us from evil!’

Her half-brother Axel bounded towards her through the villa’s garden, his face alight with excitement. ‘Have you heard? The Luftwaffe have blown the port at Piraeus to bits! Won’t be long now before stormtroopers march into Athens.’ He began to goosestep around her, one arm held high in the stiff Nazi salute.

‘What in God’s name is wrong with you?’ Alenka cried. ‘You can’t want that! Not even you could be so stupid.’

Axel scowled. ‘I do want that! Why shouldn’t I? I’m German.’

‘You are not! You’ve never even been to Germany. You’re Greek, just like the rest of us . . .’

‘My father was German, that makes me German,’ he shouted at her.

Indeed, he did not look much like a Greek boy. He had ice-blue eyes and curly hair so fair it was almost white. His father had been an archaeologist from Berlin who had come to the Villa Ariadne to help in the reconstruction of the ruins. After he had gone home, Alenka’s mother Hesper had discovered she was pregnant. When Axel was born nine months later, as pale as a white rabbit, Alenka’s father Markos had been furious.

In Crete, there was no greater insult than calling a man a cuckold.

Markos had beaten Hesper till she could not stand. Alenka had been only seven when Axel was born, but she remembered that day all too vividly. Her father’s raised fist. Her cowering mother. Blood on her mother’s mouth, bruises on her skin. The baby screaming. Alenka’s mother falling, crawling, curling into a ball. Her father kicking her.

‘Get out,’ he had said. ‘Get out and never come back.’

So Hesper had wrapped the baby in her shawl, taken Alenka’s hand, and crept through the night to her mother Galena’s house, in the small village of Knossos. Alenka’s Yia-Yia had calmed the baby, tended Hesper’s bruises, and tucked Alenka up in her own bed by the fire. She had been a tiny, fierce, black-clad woman, as quick to curse as to bless, who wore a black cross on a long black cord about her neck, hand-knotted by the monks, for counting her prayers.

She had told Alenka a thousand-and-one stories, and taught her how to cook and clean and scrub and sew. ‘Alas, you too will need to be married one day,’ she would say, ‘and it will be hard for a man to forget your mother’s shame. Like mother, like daughter, they will say.’

So Alenka had decided never to be shamed by love.

Her half-brother, meanwhile, had grown up forged by hatred. He was twelve now, and like a boy carved from marble. Perfectly formed, but cold through to the core. The only person he did not hate was his absent father. Axel was obsessed with knowing who he was, and pored over old photographs of that summer, looking for resemblances. He tried to force his mother to tell him his father’s name, and when she refused, punched her hard. Still, Hesper would not tell.

As he grew older, Axel determined to make himself as German as possible. When he was ten, he realised that he had been born on Adolf Hitler’s fortieth birthday and developed a fixation on the Führer that was truly frightening. He began to collect cigarette cards that featured photographs of Hitler, and would arrange and rearrange them obsessively. Alenka’s godfather Manolaki had burned them all one day. Later that day, the shed where Manolaki made his fortified wine mysteriously caught fire. Everyone feared it had been Axel.

Alenka found she was rubbing an ugly puckered scar on her arm. She took a deep breath, and said, ‘Axel, I know your father is German, but you cannot want Greece to be invaded and defeated . . .’

‘I do,’ Axel said. ‘The Germans will come, and I will join up and fight for them, and they’ll give me a machine gun and I will shoot anyone who calls me a bastard, and they will think me a hero and take me back to Berlin and give me medals, and I will find my father and he will be proud of me.’

His voice had quickened as he spoke, his hands balled into fists in a way Alenka knew all too well.

‘Axel, that’s never going to happen. Didn’t you see the photos of what they did to Belgrade? We will be bombed to smoking ruins just like that! People will die. Innocent people, women and children.’

‘I don’t care! I hate them. They’re all mean to me – they deserve what’s coming to them!’

Alenka bit her lip. Her little brother did have a hard time of it. She had told him just to ignore it, that the other children only teased him because he reacted so strongly, but Axel just cried, ‘It’s all right for you, they never call you the son of a whore!’

He made things more difficult for himself by punching and kicking the other children or slashing the tyres of their bikes. The adults in the village disliked him too, for Axel was always in trouble of one kind or another. Playing truant from school, stealing fruit from gardens, breaking windows with stones. Things had got worse since the war had begun, for everyone knew that Axel’s father was German. Some of the old women had even spat three times at him in the street, making the sign of the cross over and over again.

She tried to soften her voice. ‘I know you’re unhappy here, Axel, but it won’t be forever. If you’d just go to school and work hard, then when you’re finished you’ll be able to do whatever you like.’

‘Which is why you’re still here in Knossos, sewing your dowry like a good little Greek girl.’

Alenka’s face burned. Axel had such a way of prodding sore points. How could she explain how calming she found it, setting one small steadfast stitch after another, watching flowers and birds and dancing figures bloom from the end of her needle? It did not mean she was a good Greek girl. Good Greek girls walked three paces behind the male of the family, stood quietly against the wall and watched while the men feasted, ate only when they had finished, then did the washing up while the men played cards, drank tsikoudia and argued about politics. Good Greek girls wore a headscarf and an apron over a skirt that reached their ankles, and married the man their father chose. Good Greek girls cooked and spun and wove and washed clothes and scrubbed floors from dawn till dusk, while their little brothers ran free, indulged from birth simply because they were male.

Alenka had rebelled against all that since she was a child. It infuriated her that Greece was the home of democracy, but she was not allowed to vote. What sense did that make? She was just as intelligent and capable as any man. Her heroines were the poet Sappho, the freedom fighter Laskarina Bouboulina, who had commanded her own fleet during the Greek War of Independence, and the singer Sofia Vembo, whose sultry songs had captured Alenka’s imagination that past winter. Sofia Vembo dressed like a Hollywood star, was photographed with bare shoulders and a smouldering cigarette, and was known to have a lover. She had inspired Alenka to pluck her eyebrows and shorten her hems, despite the scandalised looks of some of the older women in the village.

‘Axel, you can’t really want the Nazis to invade us,’ she said, trying to recover her poise. ‘They’re so cruel. We’ll be enslaved.’

‘Good!’ Axel kicked her sewing basket hard. It flew across the courtyard, spilling her pins, needles, thimbles and spools of thread over the ground. Alenka jumped up, exclaiming in anger. He seized her embroidery and flung it to the ground, grinding it into the dirt with his grubby bare feet, then evaded her clutching hands and ran off, laughing.

‘You are such a little brat!’ Alenka shouted after him. She picked up her sindoni, shook it free of dust, and put it neatly on her chair. Then she took out a cigarette. Her hands were shaking so much it took her a long moment to light it. She stood, smoking, looking out across the ruins of the old palace.

Axel was right. Alenka was very afraid.

For her little brother, as much as for herself.

The Crimson Thread Kate Forsyth

Set in Crete during World War II, Alenka, a young woman who fights with the resistance against the brutal Nazi occupation finds herself caught between her traitor of a brother and the man she loves, an undercover agent working for the Allies.

Buy now