- Published: 18 April 2023

- ISBN: 9781761041570

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 432

- RRP: $28.00

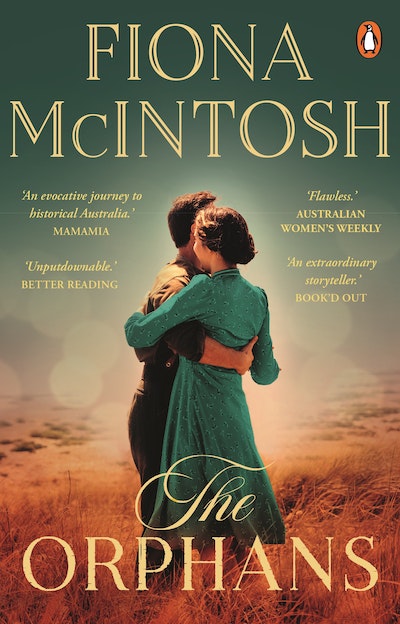

The Orphans

Extract

Irma was Fleur’s stepmother, but even that term was loose, in Fleur’s opinion. She thought of her more as a conniving limpet of a woman, who had clung fiercely to Henry from the moment he had looked at her and used his grief at being widowed to steal Mae Appleby’s role for herself. To Fleur it had been a sly and orchestrated campaign to win her father’s affections; the horrible woman who now sat in Mae’s chair had shown such patience that Fleur almost believed that beneath Irma’s skin lived a reptilian creature of ancient cunning. She had tried over and again to find qualities to admire, just one thing to like about Irma – perhaps the affection between her and Fleur’s father – but she had come up wanting. She had never seen a fondness coming from her father, nothing even resembling love.

Now, as an adult, Fleur believed the marriage had been one of convenience on both sides. It suited Irma’s social climbing aspirations as much as her need for security. And what her father got out of this arrangement, Fleur had often worried over, and she had finally settled on him simply wanting a wife to run a household and the child within. It appalled her that he’d relegated her mother’s role to something so practical, given how loving they had been towards each other.

These days her father made no pretence of his indifference towards Irma and had taken to reading the evening newspaper at the dining table, something Fleur knew her darling mother would never have tolerated. What’s more, her father would never have put up such a barrier between himself and his women had Mae still been living. Her early death from influenza had changed all their lives in so many ways, reading at the dinner table one of the least intrusive. The worst was making Henry so vulnerable to a predator such as Irma.

‘You can clear the dishes, Nan,’ Irma said with her fake smile, dabbing at those mean lips that seemed to be permanently chapped. ‘Coffee for Mr Appleby.’

‘I don’t think—’ Henry began.

‘Nonsense, dear.’

Fleur would have gladly helped but she knew it would raise her stepmother’s ire. She continued to find new pretensions to focus her attention on. The last few years had been about jewellery and acquiring more of it to show her husband’s wealth. Right now, though, Irma was fixated on the notion of domestic help, and how that spoke of wealth and position.

The household currently had a staff of two. Nan was a sailor’s wife with a clutch of children and a need for income, and had entered their lives just a few weeks prior as a cook and server. Fleur didn’t believe she was particularly competent at either but she was cheap and looked the part in her new uniform. A cleaner, Jean, had been keeping the house dusted and tidied for half a year now.

Fleur thought about her lovely mother, who had happily run the household alone, raising a child among those duties, but was now eighteen years in her grave. Her father had held out for a couple of years; it was hardly a happy life without Mae, but they’d managed well enough as father and daughter, despite the hole she left because of the deep affection between them. And yet somehow Irma had got beneath his skin and, likely during a drunken moment, coerced him to get married.

So here they sat. The world’s unhappiest trio around a table where the happiest of families had once eaten. Fleur shook her mind free of the past. It did her no good.

‘What is happening in the world to make you cross, Dad?’ She knew he still enjoyed a conversation about news and events with her. Irma would only join in if it was salacious, involved some sort of purchase or, best of all, offered an opportunity to make money. He didn’t look well; he was pale but it would only vex him to mention it.

‘Not cross. Concerned. This beef riot they’re talking about is going from bad to worse. We’ll be busy if they keep this up, because people from the port are going to get hurt or even die with all this hostile feeling flying about.’

Fleur sensed Irma’s interest was piqued at the mention of bodies and burials.

‘Nothing is bad that’s good for business, Henry,’ Irma predictably said, as though making some grand philosophical point. ‘Er, Nan, we’ll take coffee in the drawing room now,’ she said in the lofty voice she reserved for servants or her father’s funeral workers.

Drawing room. It made it sound as though they lived in a vast manor. Fleur’s mother had called it the sitting room, which sounded far cosier and was more accurate, given its small size.

Fleur returned her focus to the news item, eager to hear more and keep her father engaged. The riot her father mentioned had broken out somewhere near the city when the unemployed discovered that mutton would be substituted for beef on the ration list.

‘Henry, shall we go through, dear?’ Irma put down her napkin and made to stand, leaving a ghastly imprint of her lips on the starched fabric from the plum lipstick she favoured. ‘Henry?’

There were times when Fleur believed this careless attitude was deliberate, to show disdain for the woman who had come before her. Irma knew how much Mae’s belongings still meant to the people she had left behind and now, watching that oily stain landing in full view, Fleur was convinced that Irma meant Fleur to see it. She looked away as her father growled.

‘What?’ he said rudely, frowning as he again folded back the newspaper, disgruntled to be disturbed.

‘I said, Henry, we’re taking coffee in the drawing room.’

‘You go through.’ He flapped the paper again.

Irma glanced at Fleur, who maintained a neutral expression. She hoped it conveyed a sense of ‘don’t blame me’, but what she really felt was helpless delight. When had she become so petty that she would inwardly smile if her father favoured her over his wife? It seemed that she and Irma had taken positions on opposite sides of her father. Anytime he moved against Irma – even in a tiny way, like choosing to stay seated a little longer where Fleur happened to be – was apparently a choice in his daughter’s favour.

‘Tell me more about what the article says,’ she said, turning back to him, far more interested in her father’s doings than Irma’s.

‘Henry?’ Fleur could sense her father’s blood pressure rising as Irma nagged again in her sniffy nasal voice. ‘Don’t let it go cold, please.’

Henry gave another grumbling sound and Irma left, her wide hips grazing the tablecloth and rumpling the corner. Fleur straightened it – it was her mother’s lace and she hated that Irma made use of her possessions. This was one of her mother’s favourites and yet Irma used it for midweek suppers; she could see where Nan had dripped stew from the pot to her father’s plate, but she couldn’t blame Nan, who was a former flower seller, not a waitress. It seemed Henry was oblivious too; either he chose not to see the stains on his first wife’s precious lace, or he no longer cared.

‘Here, listen to this,’ Henry said. ‘Apparently the unemployed in our neighbourhood are demonstrating in the streets tomorrow against the abolition of beef in their meat ration. They’re mustering at the Waterside Worker’s Hall.’ He folded up his newspaper and sighed. ‘There’s two thousand going from Port Adelaide, but they’re meeting up with plenty of others once they hit town. They’re threatening to carry signs with the hammer and sickle!’

Fleur gave a soft shrug. ‘They have legitimate grievances. I was talking to Mrs Brown the other day – you know her husband hasn’t had work for a couple of years, and they have five mouths to feed?’ She didn’t wait for him to answer. ‘She told me their rations had gone down from four loaves to three in the last year, and even the value of their groceries were reduced by threepence. She said they had more at the height of the Great Depression a few years back than they do now.’

Henry clicked his tongue with disgust, reassuring his daughter in doing so that he still did feel something for others. She watched him reach for his glass again to drain the ale and winced internally. He was drinking heavily. It had been escalating since her mother died – year after year it became more noticeable but now she was convinced that her father was an alcoholic. It didn’t matter that he was sober for the day’s work; come the evening – and Irma – he let go into his cups. She reckoned he’d suffer coffee in Irma’s drawing room briefly but would be out to the pub as fast as he could.

‘Dad?’ She might as well strike while he was lucid, and especially because life in this household was worsening by the week.

‘Hmm,’ he said, absently, folding his glasses into their case.

‘I’ve got some ideas I’d like to discuss.’

He closed his newspaper, obviously aware that he was being impatiently awaited in the other room. ‘What ideas?’

Fleur smiled. ‘Mainly for our business, but one personal one I would like to talk over with you. Can we arrange to sit down together tomorrow, perhaps?’

‘Your mother’s insisting—’

‘She’s not my mother,’ Fleur said, helplessly fast, like a whiplash. She wished she hadn’t, because his eyes narrowed.

‘She’s the only mother you have and—’

‘I didn’t ask for one. I was happy with just us.’

Henry sighed. And she understood – it was an old bleat and she should have resisted making it once more. ‘Don’t start again, Fleur, I’m tired of it.’ His expression looked suddenly wearied, as if he alone carried all the weight of the world’s troubles.

But Fleur knew exactly what his private troubles were, and they all focused around one topic. ‘Why did you marry her, Dad?’ she murmured. ‘You look unhappier now than you did years ago when Mum became sick.’

‘Too late for regrets. We have to make the best of it.’

‘I don’t have to. I want to leave.’

He looked stricken. ‘The business?’

Fleur shook her head. ‘Just the house, Dad. I don’t think I can live here much longer.’ It was all tumbling out the wrong way.

‘She’s so grasping, I can’t bear it. You give her everything and it’s not enough. She’ll ruin you, Dad.’

‘She’s just uncertain of her place,’ he said, falling back on his usual generous way. ‘You’re so assured and reminders of your mother are all around us. It’s probably hard for her.’

‘Oh, Dad,’ Fleur said, sounding frustrated. ‘There’s nothing hard for Irma in the life you’ve given her. She’s fortunate you’re so big-hearted.’

‘You miss your mother, I underst—’

‘Don’t you?’ She regretted the accusatory tone immediately as pain fleeted across his features, taking them from that resting expression she knew and loved to one of grief again.

‘Every day, child. But you needed a mother back then, can’t you see that?’

She nodded but it was a lie. She had never needed anyone but the person who had died, and once Mae was gone, Fleur would have got along as best she could with one parent. But she knew he would tell her that Irma came into their lives for the right reasons. And she would take that moment, if it presented itself, to express as sharply as she dared that Irma was an actress and only pretended to love them, that she hadn’t had much to say to Fleur since she’d first bled and been considered a young woman, no longer a child.

‘Irma sees you as family, Fleur.’

She fixed her gaze to his. ‘Irma sees me as a rival, Dad. For your love, for your business, for your property – and especially your bank account.’

He gave a groan of despair as the very woman they were discussing called out again.

‘Henry!’ Her shrill voice came from the room where the coffee was clearly cooling to where they were now all but whispering.

‘Come on,’ he said. ‘We’ll talk at length about what you have in mind tomorrow, when we’re in the mortuary. Right now, let’s just keep the peace, can we?’

She gave her father a small smile with a nod and stood. The meeting tomorrow was a positive step. ‘All right. Tomorrow.’

The Orphans Fiona McIntosh

The highly anticipated new historical adventure by the bestselling author of The Spy's Wife.

Buy now