Geoffrey Blainey digs into the Australian rabbit invasion of the 1800s.

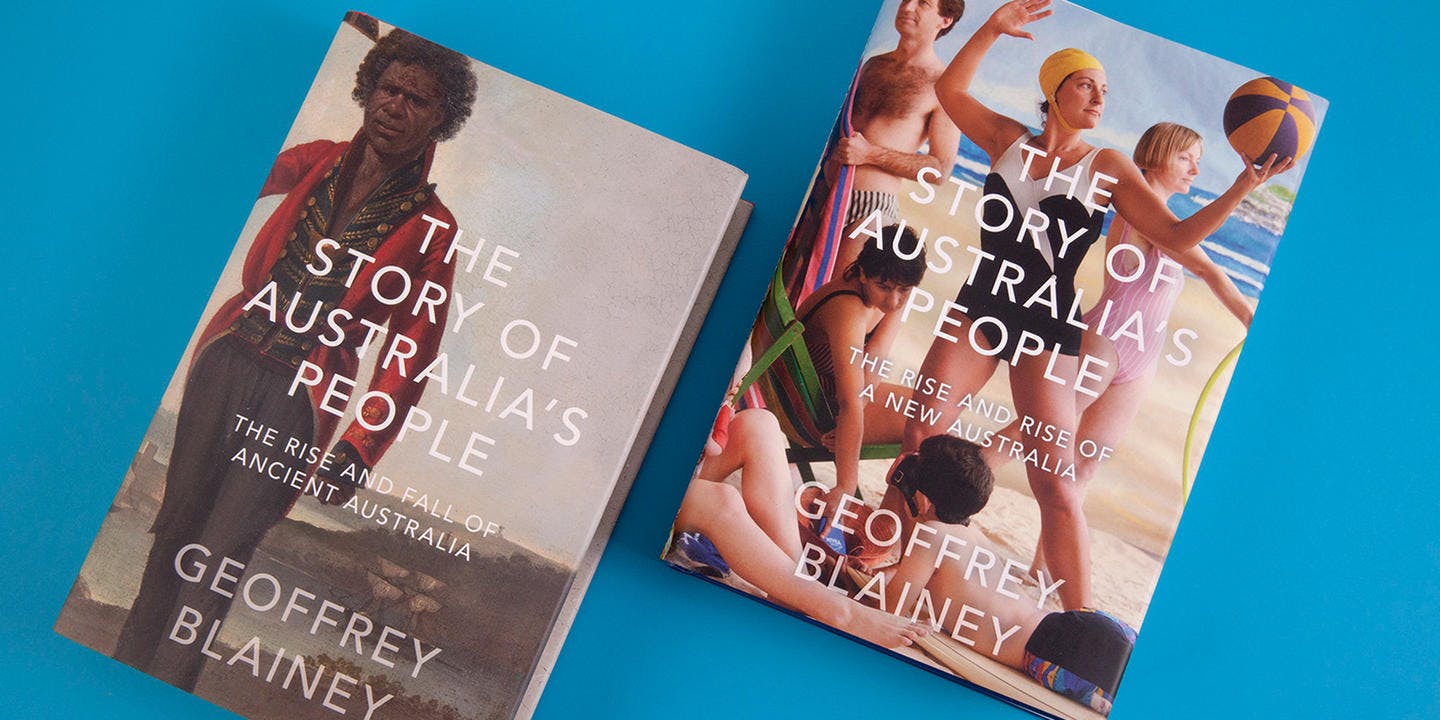

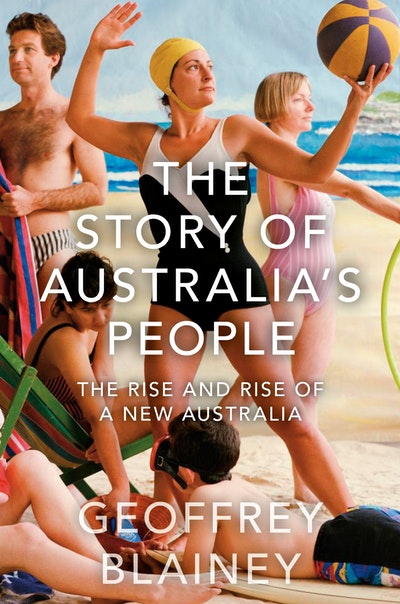

The Story of Australia’s People Volume II is the second instalment of an ambitious two-part work, and the culmination of the lifework of Geoffrey Blainey – Australia’s most prolific and wide-ranging historian. When Europeans crossed the world to plant a new society in an unknown land, traditional life for Australia’s first inhabitants changed forever. As did Australia’s landscapes.

‘The first volume tried to piece together the Aboriginal peoples’ way of life – often ingenious – that changed slowly in the course of thousands of years before the arrival of the British in 1788,’ writes Blainey in the Preface of Volume II. ‘Then came the swift decline and disarray of the Indigenous peoples, as the more fertile parts of Australia became a British land… This second volume carries the story through momentous changes, many being unexpected, into the twenty-first century.’

Of all the changes detailed in the book, the impact of a small furry animal stands as a shameful demonstration of European settlers’ disregard for the natural environment. We still live with the environmental legacy of the introduction of rabbits in the mid-1800s. Straight from the pages of The Story of Australia’s People Volume II, here Blainey gives some historical context to the beginnings of this ‘wide grey tide’.

On Christmas night of 1859 the elegant Liverpool clipper ship Lightning reached Melbourne with passengers and a small consignment of livestock. It is doubtful whether any cargo loaded at any port in recorded history was to prove more fecund than the small animals that were carried ashore.

The twenty-four wild rabbits – along with five hares and seventy-two partridges – had been shipped from Liverpool to the English-born squatter Thomas Austin, and were promptly carried past Geelong to his estate at Winchelsea, on the undulations of the Western District. Austin was a sportsman and employed his own gamekeeper to care for the consignment. The partridges were placed in an aviary and later they were joined by English blackbirds and thrushes. At least thirteen of the rabbits were imprisoned inside a paling fence and they too began to multiply. Though the popularity of the phrase ‘to breed like rabbits’ belonged to the future, it really commemorated the activities of Austin’s rabbits.

Soon, so many rabbits ran about his sheep run near Winchelsea that he invited friends to join him on shooting excursions. His hunts followed the English country tradition, and he employed men as beaters to frighten the rabbits and drive them within range of the hunters’ guns. In the year 1866 he and his guests shot 448 hawks, 622 native cats, 32 tame cats and a total of 14 253 rabbits. Austin now lived in a hunter’s paradise of his own making. The rabbits were established securely on the grasslands that seemed heaven-made for them, and the grasslands ran without a break or barrier to South Australia and New South Wales and even to Queensland.

Years later, when the rabbits had become a plague in about half of the continent, the popular belief was that Austin was solely to blame for the terrible invasion. He had been a squatter, and so he was a suitable target. His elaborate shooting parties had been described in the newspapers almost shot by shot, and it was common knowledge that he had bred thousands of rabbits, so he was more conspicuous than other landholders who had quietly imported or bought rabbits in South Australia as well as Victoria. It was also the popular belief that the rabbits – by then respected as a foe of herculean strength and fertile mind – had spread of their own will all the way from Austin’s land to new warrens as far as 3200 kilometres away. Recent investigations suggest that the rabbits possessed many other human allies in their first years. Other English people nostalgic for home applauded their appearance, and both landowners and rural labourers carried the rabbits in baskets and boxes to their own homes and gardens and hoped that they would multiply. That they did multiply was aided by a succession of favourable seasons: droughts were infrequent during the rabbits’ initial decades of rapid advance.

The rabbits in lush years now spread at lightning speed. One or two could suddenly appear as if making a reconnaissance, and yet the nearest known colony of rabbits might be 80 kilometres away. Along the Darling River in the early 1880s the unexpected arrival of the first few rabbits made some pastoralists wonder whether they had been deliberately released by passengers travelling in the paddle-steamers.

‘The rabbits are coming, the rabbits are coming’ became a familiar warning in dozens of districts in the last third of the century. Many flock-owners who were warned of the coming horde made their own precautions. George Riddoch, a South Australian with sheep runs in three colonies, lost so much money when the rabbits overran his land near Swan Hill that he took pains to defend another of his sheep runs north of the Darling River about 1883. He knew the nearest rabbits were still 160 kilometres away and so he gave orders that men were to be employed on his boundary as patrollers. Their task was to watch for any trace of rabbits – any dung, fur or scratchings in the ground.

And then the rabbits came, a wide grey tide. By the first month of 1887 Riddoch employed 125 rabbiters. More of his employees were now catching rabbits than were, presumably, carrying out all the station’s other tasks put together. By the end of the year on that one property, his men had caught more than a million rabbits.

All the time the search went on for the remedy that would sweep the species from the land. In the hope of reducing the pest, they used iron traps, cats and ferrets, hunting dogs, guns, nets, fumigants, and all kinds of concoctions and devices. Bushmen soon had as many recipes for poisoning rabbits as housewives had for cooking them. A mixture of phosphorus and sugar and cold water was added to bran and left on the ground as bait. Another tempting mixture contained phosphorus, flour, and wheat or oats. Many farmers mixed baits of chaff and arsenic, or quinces and strychnine, or arsenic and carrots.

By the early 1890s the rabbits were thriving in most parts of Australia south of the tropics. They were at home in the hot half-deserts where a furry creature seemed the most unlikely inhabitant. They flourished on the riverbanks and in the sandhills. They revelled in the plains and ran on to the colder tablelands. Even where the grass was scarce they could flourish because they ate the saltbush and other low plants or the bark from mulga, sandalwood and stunted trees, effectively ringbarking and slowly killing these trees. As the leaves of these trees were a reserve of fodder for sheep and stabilised the soil, their destruction was costly.

In the hope of containing the rabbits, long rabbit-proof fences were built by governments. Among the longest fences in the world, one was built across a vast tract of Western Australia. It stretched for 1833 kilometres, from the Southern Ocean near the port of Esperance, to a tropical beach beyond Port Hedland. That fence was begun too late, and when the wooden posts were in place the rabbits had already slipped by and were feeding in the fertile strip of Western Australia.

How the rabbits reached Western Australia was a puzzle. The evidence is powerful that their ancestors came west across the dry Nullarbor Plain, not far from the ocean. On several of the harsh stages of that journey, kitten rabbits had probably been carried in an empty billy by travellers, to be released by a waterhole and a patch of green grass, there to multiply – while the grass lasted.

Almost everywhere, the rabbits indirectly became a form of social welfare. They transferred money from wealthy squatters to rural labourers. Thousands of professional rabbiters with their dogs, traps, nets and poisons made a high monthly income by destroying rabbits on the large pastoral stations. Hundreds of these rabbiters then turned from poisoning the rabbits to trapping them for the English market, and in the year 1906 Australia was to earn more by shipping away rabbit meat and skins than by shipping frozen beef. In that year 22 million frozen rabbits were exported, mostly to London, and rabbit pies were probably eaten in cottages close to the English woods where the progenitors of the pie had run wild only half a century previously.

In many years perhaps one-twentieth of Australia’s potential income from wool was devoured by rabbits, and even more in bad years. One sheep-owner in the Cobar district began with

16 000 sheep but in the year 1892 his flocks were reduced to a mere 1600. Asked for the explanation, he replied in three simple words: ‘the rabbit invasion’. On scores of large sheep stations the rabbit trappers made a living in nearly every year until the 1950s, when the deliberate spread of the myxomatosis disease began to decimate the population of rabbits.

Much of the early history of Australia is a story of the lottery of transplanting. The Austin family, of rabbit fame, knew the variations that this theme could play. The first Austin to arrive was a young Somerset convict, who had stolen beehives and honey. In Tasmania, after his sentence expired, he acquired farms, a big orchard, an inn, and a most profitable river ferry. He was childless and his nephews who came out inherited his money, and James and Thomas Austin moved to Victoria with the first sheep and prospered.

James Austin returned to England and bought the abbey house and the famous ruined abbey at Glastonbury. He presided over the place where King Arthur was said to have been buried and where pilgrims came in medieval times to see the famous thorn tree that they believed had been planted by Joseph of Arimathea. According to legend, Joseph had come to England as a missionary and had placed his priestly staff in the ground at Glastonbury and it had sprouted as a thorn tree, flowering twice a year – the symbol of the miraculous. On this sacred site James Austin, returning from Australia in 1856, had settled down as proprietor.

It was he who arranged, three years later, that the cargo of English rabbits be sent to Liverpool for shipment to the Victorian estate of his brother. When as an old man he made a final visit to Australia he must have been astonished to see how these furry ‘thorns’ had multiplied.