- Published: 31 July 2017

- ISBN: 9780143783831

- Imprint: Ebury Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 416

- RRP: $40.00

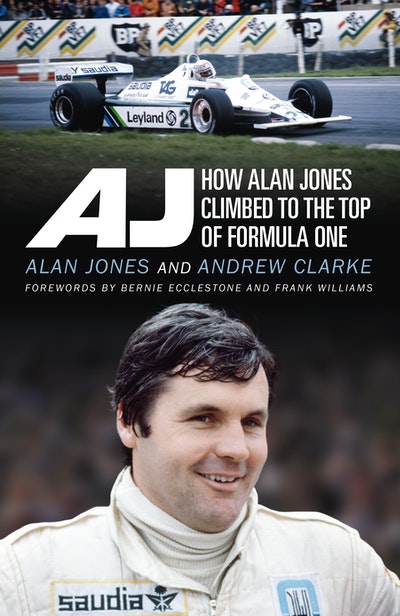

AJ

How Alan Jones Climbed to the Top of Formula One

Extract

I didn’t go racing for anyone other than myself and, to a lesser degree, my team. I didn’t crave fame – in fact, I worked hard to avoid it, although I did enjoy some of its trappings. In my early years, I made it clear to anyone who employed me that I was there to race and to race hard enough to win. If you couldn’t help in that quest, I was going elsewhere.

I believe I acted throughout my career with honour and stuck to the values I have held since my early years. I have never wanted anything more or anything less than has been agreed. If we do a deal, I expect you to honour your part of the agreement, just as I will mine. My old man also taught me manners come cheap. They cost nothing. Everyone deserves respect: a waiter, a bellboy, a cleaner – say thank you and don’t take those people for granted. I’ve tried to stick by that all my life: not to be arrogant and to treat all people the same way. In many ways, despite my dad’s flaws, I did learn from him . . . in some ways I am more like him than I ever wanted to admit.

We are all affected by our parents, consciously or subconsciously. I was born in November 1946 and I was only 12 when my parents split up and my father, Stan, went broke a decade later. Those events were big lessons for me, and helped shape who I became, even if I didn’t know it at the time, even if I don’t fully understand it today, 60-odd years later.

My parents’ marriage was volatile. I remember the police coming to the house a few times. The old man was a fantastic bloke. He had a heart as big as Phar Lap: you’d be going along with him and he’d see a homeless person and he’d stop and give him five quid. But he’d rather a fight than a fuck half the time, and was a bit inclined to give Mum a biff, which upset me. She’d call the police and they would come around and then there’d be a full-on blue in the house with him and the police . . . he wasn’t scared of having a go at them either. In fact, I don’t think anything frightened him, but he was extremely kind to me.

While it upset me, there was nothing I could do, so you just carry on like it wasn’t happening. I don’t think I was ever the sort of kid that would say, ‘Mum, could we sit down and have a talk? I’m a bit worried about the old man hitting you.’ I wasn’t even that person as an adult. It was never discussed.

But I am not my father, just as my son Jack is not me. Jack is totally different to me; he doesn’t care about motorsport for instance. He loves his soccer and he has a beautiful temperament – unlike me. He might turn out to be a real prick, I don’t know, but at the moment, he’s a lovely boy. I worry for him though, because boys like him get into trouble they are not looking for.

Whereas Zara, his twin sister, she contributes to most of the aggro in the house. I brought some sushi home one night and it was the wrong sort. She got stuck into me, so I threw it in the rubbish. To which she sarcastically said, ‘Oh, welcome back.’ She’s not scared of giving it to me. Zara is me and Jack is Amanda, their mother, which makes life interesting.

So I didn’t suck my thumb and curl up in the foetal position upstairs at night, thinking about it; no, I just rolled on. That’s the way it was, that was the kind of man my father was and I couldn’t change it, so I had to wear it. Mum too. I remember him for all his good characteristics, not his bad habits. You might consider that to be denial – I don’t know about that, nor do I care. The one thing I did take away was that I would never hit a woman, and nor would I allow a woman to be hit if I could do anything about it.

Dad was raised by his grandfather in Warrandyte. He was a bastard in the true sense of the word and he was self-made because of that. I’m sure his childhood was tough; everything he had or did, he created himself.

My mum, Alma, was typically Irish, stubborn as a mule and never taking a backward step . . . something to do with the red hair I suspect. She’d rev Dad up something shocking, call him something and that would be enough for him to give her a whack. It wouldn’t stop her though – if you gave her a backhander she’d just come back for more, mouth off even louder. He was volatile and had a very short temper . . . it didn’t make for a good mixture.

Mum was one of three girls – Auntie Maude, Auntie Nell, and Mum. There was a brother too, Jack, who got killed driving his truck up at Ballarat. When that crash happened, the old man had a brand-new Jaguar XK120, and he ripped off the governor – the device that limited its speed – and screamed up there. I used to go in the truck with Jack quite a bit, its name was Leaking Lina. He was a lovely guy.

They were a reasonably close family, which was obviously different to Dad’s. When Mum and Dad used to go out for dinner, they’d drop me around to Nanna and Pops. I’d go to the local pictures when I was there, because in those days you could walk down to the picture theatre at night by yourself, even as an eight-year-old. I’d be too scared at my age to do it now.

It’s funny, I look back on my childhood now and can see how abnormal it was, but at the time I had no idea. I thought Dad and his girlfriends was a normal thing. When they got divorced I ended up living with Dad, which was unusual at the time. Still is. Mum was keen for it to work, and if I’d had a choice that is what I would have asked for too, so everyone was happy. The old man pretty much got what he wanted most of the time, and this was just another example. We were living in East Ivanhoe, in Melbourne’s north-east, and he had the Holden dealership in Essendon, over in the north-west, about 20 kilometres away.

Mum went off and married a man called Wally, and then my parents became the best of friends. The old man and I would go around to their place for roast dinners and the like. Most people would say, ‘Christ, what a weird set-up that was.’ I didn’t really see any problem: it worked.

Mum was a very good mother and wife. Without fail, every day when she was with Dad, she’d stop housework at a certain time, have a shower, get fresh clothes on, put the perfume on, and get dinner ready. She always made sure she was well presented and looked good when Dad came home. Unfortunately, half the time he never came home, which was a bit of an issue. She knew he mightn’t, but she got dolled up anyway, come what may.

Mum was fiercely loyal: she would always stick up for me and would do anything for me. She was in charge of choosing the places for my schooling. I started at All Hallows, a Catholic primary school in Balwyn, and then I went to Burke Hall, the junior school for Xavier College . . . again Catholic. My mum was the Catholic in the family; her father’s name was Paddy O’Brien, which speaks for itself.

I was certainly no scholar. I thought I was far too good and clever to worry about sitting down and learning anything. How the hell, I thought, was Latin going to help me buy and sell cars, or race them? Which of course Latin – and everything else – does, in a roundabout way. But when you’re Mr Smart Arse aged 13, you don’t think about education or getting help from anyone. My objectives as a child were strictly those of the day I was living in; tomorrow didn’t exist.

Dad was the sort of person who really couldn’t give a shit about religion. If Mum had said she wanted me to go to a Jewish school, he would’ve said, ‘Yeah, right-o, whatever. As long as he’s out of my way and being educated and he’s happy.’ She was the one that wanted me to go to Xavier. Burke Hall was in Studley Park Road, which wasn’t too far from where we lived, and then from there I’d go to the big school for the rest of my education . . . well that was the plan.

I won’t say I was expelled, but I think the school suggested to Dad that it’d be better if I finished my education elsewhere. Then he sent me to Taylors Business College, which was basically a place for kids that had been asked to leave private schools, so that their parents could hold their heads up in their social networks and say, ‘Oh no, he’s going to a business college.’ Which was just bullshit. It was on the sixth floor of a building in the CBD of Melbourne.

I finished off my last year or so of schooling there, but for me it just didn’t matter. I was a shocking student, I wasn’t academic at all. It was a complete waste of time – not that I want my kids to have the same attitude. But I knew what I wanted to do.

I had something other kids didn’t have. Racing was my chosen goal; my father was a racing driver and because Stan Jones was known to be good, I could also be good. I grew up with his mates and his mates’ sons, and every last one of them was going to go racing, too: which they invariably didn’t. But for me, there was this great big billboard in my mind that said, I’ve got to do it. School, in my eyes, was of no value. I wanted to be a racing driver and that was it. All this was just filling in time.

My Catholicism didn’t last. Burke Hall turned me off. They used to strap me for blowing my nose the wrong way. You didn’t have to do much and those pricks would pull out these long straps they kept in shoulder holsters. They were leather with steel in them, and they used to soak them in vinegar just to make the leather a bit crisper. You’d have to hold your hand out and you’d either get two, four or six of the best, depending on how much you flinched.

The trick was to try and pull your hand away, so you took a lot of the sting away. You had to time it perfectly, because if the prick thought you did it too much, he’d go again.

One day during catechism, where we’d be taught religious knowledge, Father Brown belted the shit out of me for not knowing why Jesus was kind and gentle. I thought, ‘Hang on, this prick is his representative on earth, and he’s belting me up for not knowing why Jesus was kind and gentle.’

That’s when I became an agnostic.

There was a lay teacher, Mr Tilley. He hit me with a ruler and cut my eye open once. The old man was so angry he flew up there and dragged him out of the classroom. Mr Tilley was screaming like a sheila. Dad whacked him, which not too many parents at Burke Hall or Xavier would do. But what others would do didn’t ever stop him.

The school didn’t do anything about it because Dad was going to press charges for assault on me if they did. After that Mr Tilley used to shit himself every time he saw me; he wouldn’t come anywhere near me. Good.

*

I like to take things as they come. I always believe that tomorrow is another day. It doesn’t matter how bad things get today, you go to bed and tomorrow is another day, another opportunity.

It’s like in my racing career – I was always able to sleep well the night before a race because I wasn’t overthinking things. You’d get to the circuit and some drivers would say, ‘I didn’t sleep last night.’ I used to think, ‘Jesus, why tell me that? You’ve just shown me a chink in your armour.’

I used to say, ‘Oh really? I slept like a log. In fact, I slept in,’ which I didn’t. Those mind games are part of the game. I was competitive. I looked for every advantage. I looked for weaknesses in my opponents.

That was something I got from the old man, as was the whole motor racing thing. It was in my blood, if you believe in that concept, which I am not sure I do. You’ll find out why soon. The old man was good enough to be offered drives for Ferrari and BRM, but he had a young son and a business that was going quite well, so he turned them down.

One of the guys he was racing and beating was Jack Brabham, who did take those opportunities, went to Europe and won three world championships. The truth is though, the old man could drive Brabham into the weeds. And he did so. When Brabham was New South Wales champion and Dad was Victorian champion, they had a grudge race at Holden’s home, Fishermans Bend, in Melbourne, just the two of them. When Brabham crossed the finish line, my old man was already out of his car sitting there drinking a Coke. I admire everything Brabham did, but I reckon my old man was as good or better as a driver.

Dad took his regret for not taking those opportunities to his grave, especially after his business went broke and he was left with nothing. I didn’t want to die with regret. I didn’t want to live under a question mark of ‘what if?’ My old man died wondering whether he should have gone to Europe or not; there was going to be no question mark over me. I decided I’d go over, give it a good go and if I turned out a failure, I could still look at myself in the shaving mirror and say I’d given it a go, had some fun and had some stories to live on. But the old man died with the question hanging there.

*