- Published: 1 August 2023

- ISBN: 9781776950409

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $40.00

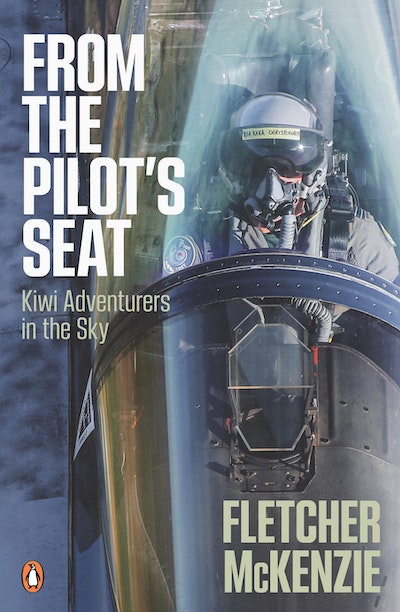

From the Pilot's Seat

Kiwi Adventurers in the Sky

Extract

Surviving to Thriving

John Martin

A top-dresser, a jump school owner, a plane crash survivor...

My father was a pilot. I grew up around Tauranga and spent my childhood days hanging around the airport trying to bludge flights on whatever aircraft I could with whoever would take me. From a very young age, I had aviation in my blood.

Before I started flying, I got into skydiving. At 16, I made my first parachute jump, eventually completing 650 skydives. At 18, I bought my first aircraft, a Cessna 150 two-seater, with a few other guys and learned to fly in that. The 150 was an old A model in rundown condition. Four of us had formed a syndicate, putting in $2000 each, and for $8000 we had an aircraft that I felt was the most beautiful plane I’d ever flown: cheap to run, cheap to operate and a great hour-builder. I spent many an hour just flying around the coastlines. I circumnavigated New Zealand once, gaining hours and seeing the beautiful country we live in. I ended up doing 500 hours flying in it.

After the 150, I got into commercial flying. I went to school, passed my exams and had my commercial pilot licence. My first job was with Island Air, operating out of Tauranga. There were three parts to the business. The first was an air service they ran out to Mōtītī Island, carrying passengers and freight, done with a Cessna 206 and a de Havilland Beaver. We also used the Beaver on the second part of their business, which was a live crayfish run. We’d fly to Milford Sound, pick up a load of live crayfish, stay overnight, then fly back to Tauranga the next day. It was exciting flying, as it was all VFR down the West Coast of the South Island, which is notorious for bad weather. If the weather forced us to stop, it would mean the end of the live crayfish, an expensive cargo.

I remember a particular incident flying south across Cook Strait, doing a solo run in the Beaver. The cockpit was large — all the unnecessary seats were removed so we could put as much freight in as possible — and I had my maps next to me, along with all the information I needed, such as fuel burn. It was a long trip, with navigation exercises to do on the way to make sure everything worked out. (This was in the days before GPS.)

Midway across Cook Strait, I struck severe turbulence, and my maps bounced to the back of the plane. I would need these by the time we got to the South Island to make sure I was headed the right way, so I eased myself out of the pilot seat, trimmed the plane so it would fly itself, ran down the back to retrieve the maps, then ran back up the front. At one point I was standing behind the pilot’s seat while flying the plane, getting my paperwork organised before I could slip back into the pilot seat. Before I crossed that stretch of water again, I secured my maps and items more tightly.

Weather notwithstanding, there is nothing quite like flying over the South Island — particularly the West Coast, up through the Sounds, around Milford, and down the West Coast. It’s a big country! The Beaver is a reasonably sized aircraft, but as I flew up the fiords, I felt like a little speck, flanked by mountains that seemed to tower up either side of me. It was fabulous and just beautiful. Because it was a VFR single-pilot operation, I had to get it right. The perishable freight pitted commercial pressure against safety, and it really did test all of my flying skills and abilities.

The third part of the business was topdressing, flying a Cessna AGwagon, which I got into from the start of my agriculture career, and it took me down a path in life that I never thought I’d take. In 1989, it gave me an experience I’d never forget.

I was spraying fish fertiliser, and I was returning to a job I’d been doing earlier that morning — one extra drum of fertiliser that the farmer had organised at the last minute. As I flew out there, I had a niggling feeling something wasn’t quite right. I checked and double-checked the gauges, and everything seemed to be okay, but still something didn’t sit right with me. It was just a sense, I guess, which I’m a little more tuned into now than I was back then. I approached the field that I’d been spraying earlier, diving the aircraft towards the paddock, setting up for the first spray run, opening the spray valves as I crossed the boundary fence and racing fast across the paddock at low level. Approaching the boundary fence at the other end, I pulled up into a climbing turn to the right to gain a bit of altitude and position for the second run. Still it felt as though something wasn’t right, and I scanned the gauges again; everything appeared to be okay.

Unknown to me, the fuel sender unit had failed (so there was no fuel); the engine was losing power, and I hadn’t noticed any noise change as I had a constant-speed propellor (the propellor changes pitch automatically depending on power). I dived for the second spray run. I crossed the boundary fence and pulled back on the stick to level out,but the plane continued to sink rapidly towards the ground. I stabbed my thumb into the jettison lever to get rid of the load, so the aircraft could recover, but it was too late. The plane smacked heavily onto the plateau. It hit so hard that the undercarriage splayed apart, wiping off the air-driven pump underneath it. Time slowed down, micro-seconds seemed to take hours, and I remember thinking through my options. As the plane lofted back up into the air, I saw there was a row of trees along my left-hand side and a gully going up to the right, so I banked the plane to the right and headed into the gully.

I saw a field, a clear paddock on the other side of the gully that I could belly-land the plane into. At that same time, a power wire appeared in my field of vision, spanning the gully. I still remember hearing my flight instructor shouting at me, ‘If you’re ever going to hit a wire, hit it with the prop.’

I aimed for the wire and hit it with the propellor, but because there was no power on it, it didn’t cut through; instead, it tangled around the propellor hub and then trailed out and hooked around the wing. A clear, calm feeling overcame me. Man, there’s no way out of this, I’m going to die.

I felt the plane running out of airspeed and knew any minute now it would fall out of the sky and that would be it. I felt the plane stall, tipping vertically towards the ground and heading straight down to a spot in the middle of the gully. I could see the exact point I was going to hit, and thought, This is how my life is going to end. There was no way out of it.

The impact drove the engine back through the fuel tank, which was driven back into the hopper and back to the roll cage where I was sitting — a huge concertina effect. I came out of this impact with a feeling of startled disbelief that I was okay. The engine, fuel tank and hopper had absorbed the impact. I was basically intact, without a bone broken, but I knew I had to get out. I opened the hatch and undid my harness, and the next part of the ordeal is the only bit I can’t remember, because that was when the aircraft blew up.

I staggered away from the wreckage, still feeling lucky, knowing that I’d been given a second chance and I should have been dead. What I didn’t know at that point was that I was on fire. I shouted out, ‘Somebody help me!’ and I heard the farmer, John Malcolmson, in the distance saying,‘I’m coming. You’ll be all right, mate.’

I remember rolling around on the grass as my body now swarmed in a deep searing pain — over 70 per cent of my body had been burnt — and I tried to put the flames out. It was a pain like I’d never experienced before. I’d broken my arm as a kid, and found I could hold it in a certain way where it didn’t hurt so much, but burns were like a monster that had a hold of me and wouldn’t let go.

I sat on that hillside for 90 minutes with the farmer at my side, waiting for a helicopter. They’d dispatched an ambulance from the nearby town of Te Puke, but they were lost up the road because there was no rural numbering system back then. Things were getting desperate, but I had in my mind that I needed to stay conscious. I needed to tell the doctor that I was okay, with no known internal injuries or broken bones, just burns to deal with. By the time I heard the helicopter touch down, I was slipping in and out of consciousness.

I recall flashes of the helicopter ride. Finally feeling the helicopter touch down at Waikato Hospital. The fuss and hassle as orderlies tried to get me onto a stretcher and into the hospital. (One of them passed out at the sight of me and they had to get another orderly to help carry me in.) Doors opening, and me being wheeled in. Finally seeing the white uniform of a doctor’s coat and thinking, I’ve made it. I’m here. I just need to tell him I’m okay.

I surrendered then. I left my soul and my body in the hands of the excellent doctors and nurses at Waikato Hospital and spent the next three months in intensive care. I went through so much that I never thought I’d have to go through: many operations, skin grafts, fighting infection, dealing with drugs — I was so sedated, I didn’t know what was real and what wasn’t. It was like living in fantasy land. I remember coming out of that coma with my mother at my bedside telling me, ‘You were in a plane crash. It was 15 April, it’s now 16 June. Do you remember?’ Somewhere in that jumble of images and feelings swarming around in my head, I remembered a plane crash.

The first time I looked in a mirror, it didn’t really bother me. I saw my burnt face; but there was still an overriding feeling that I’d been given a second chance and there was nothing to worry about. Perhaps it was more of an issue to other people, like my family and friends. I remember one day getting in the elevator with my mother at Waikato Hospital to go to physiotherapy, and there was instant silence. Everybody stood there uncomfortably and didn’t know what to say or do. I went to physiotherapy quite oblivious to it all, and my mother asked, ‘Did you notice people staring at you?’ and I answered honestly, ‘Not really.’ I was so wrapped up in my world, happy to be alive and back on my feet, that it didn’t seem important to me. But I could see it was important to put her mind at rest. So, the next day, we got in the elevator and I looked around and said to everybody, ‘How are you all today? Having a lovely day?’ and that broke the ice. They asked me, ‘How are you doing?’ ‘What happened?’ Off we went, chat, chat, chat. I could see I had to put people at ease.

I have to admit that, before I had my burns, I found it hard to look at people with a disfigurement and say, ‘Oh gosh, you must find that difficult’. When it happened to me, I learned that it wasn’t really an issue; it was all about your attitude towards it. I look around at what I have today — I’ve run a fabulous skydiving business for 26 years, I have a fabulous hangar and two awesome aeroplanes, I enjoy flying — and I wouldn’t trade that for anything. Yet it would have been very easy to have lain in that hospital bed feeling sorry for myself and just give up. I am very lucky to be here.

I was very fortunate with the support that I had. My mother was there the whole time at my bedside; I had my friends, skydiving friends, and a lot of peer support. I was one of the people that the system worked for. It was all on the public health system, and I had the best service and the best treatment from the doctors and the staff at Waikato Hospital. My surgeon, Peter Witterson, did a fabulous job of patching me back together. As the farmer, John Malcolmson, ran to me, he took his shirt off and dipped it in a trough, then threw it over my face. Without his actions, my burn injuries could have been a lot worse. I have so many people to be thankful for.

The nurses, in particular, were underpaid and overworked, and I didn’t make their job easy, but to me they were angels. They probably bore the brunt of my frustration and anger. I was sick of feeling sore. Everything I did — open a door, sit on a chair — was painful, and I lashed out at the people that were closest to me. I will always feel bad about that, but I think most of my friends, and those angels, are special people and they understood. I had a very supportive doctor; he saw it was vital for my recovery that I would one day be flying again.

I was flying again a year after the accident. I was fortunate to buy into a business taking over the Mōtītī Island run contract. It was run by people who had known me before my accident, and they accepted me after it. It was a great place to fly to. I would sit out on the rocks with a fishing rod, and while waiting for my next load I would contemplate life, thinking of all the special things people had done to keep me going.

A few funny things happened there, and a particular incident sticks in my mind. I’d flown a load of people and passengers out to the island; at the airstrip I noticed a tractor with a load of watermelons on the back, with these guys obviously intent on back-loading the return flight to the mainland. This was a huge load. I could see that they might fit, but it would be well over the weight limit for the plane. We began loading. About halfway through, I said, ‘That’s it, guys. I’m at my weight limit now.’

A local boy was standing there with the biggest watermelon I’ve ever seen, and he said, ‘Come on, man, just let me put one more in.’

‘Nah, that’s it, buddy. You know, I’ve already been in one plane crash. I don’t want to be in another.’

‘Come on, man, one more won’t hurt.’

‘Nah, that’s it,’ I said, standing my ground.

He looked at me and said, ‘Oh geez, that’s a shame, because this one was for you!’ It made me feel I would not get any special treatment. They made me feel normal again. It was important to get on with life.

Around 1991, I got involved in tandem skydiving, where a client does a free-fall jump while attached to an instructor. It had been invented about a year after I’d been running my Mōtītī business, and I could see that there was huge potential in it. We operated a minor operation, using a Cessna 172, which has relatively low overheads. It’s a great business and I thoroughly enjoyed it. We were able to give people a special thing that they would remember forever. When I got up in the morning and realised I had 10 jumps to do for the day, I’d smile and think, It’s going to be great to feel the wind under the wings again and give people a good time. Our timing was fortunate, enabling us to hit the growth period of tandem skydiving and see it right through to the major industry it is today in New Zealand.

I owned and operated Tauranga Tandem Skydiving for 26 years, in which time we completed over 18,000 jumps. I sold the Cessna with the business pre-COVID, and I am happy to say the new owners are doing a good job of it; it gives me great joy seeing parachutes still opening over Tauranga. Now semi-retired, I work because I want to work: doing maintenance and spending my lunch-break hanging out with the people at Waipuna Hospice playing my guitar. I am still flying two aircraft I own: a Europa XS Trigear and a Hatz biplane, which I fly to get to my boat at Whitianga. Because of my scarring, I was recently selected for filming on the Amazon Prime hit TV show The Rings of Power.

The accident changed my life. I now get pleasure out of the simplest things. Whereas I used to live on the edge, chasing excitement and action, I’ve started exploring my creative side. I’ll take my boat out for a sail, pull up into a nice bay, get out the laptop and write. I think I have a more balanced view of life. I could have never pictured myself as a writer before my accident. I feel like I cheated death, and now I have the choice to make the best of what I have. I can wake up in the morning and think, Man, it’s just a lovely day to be here. When people aren’t living their full life — when they just sit inside on the couch instead of seeing what the world has to offer — I think that’s a crime, as some people don’t get to live a normal life. It’s up to us to get out there and make the most of it. Have a go, don’t be afraid to take a risk now and then — I found that life gives a lot back.

From the Pilot's Seat Fletcher McKenzie

Enthralling tales from New Zealand pilots - both men and women - who fly a variety of aircraft around the world in a range of situations, from the domestic to the heart-stopping.

Buy now