- Published: 4 May 2021

- ISBN: 9780143775188

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $38.00

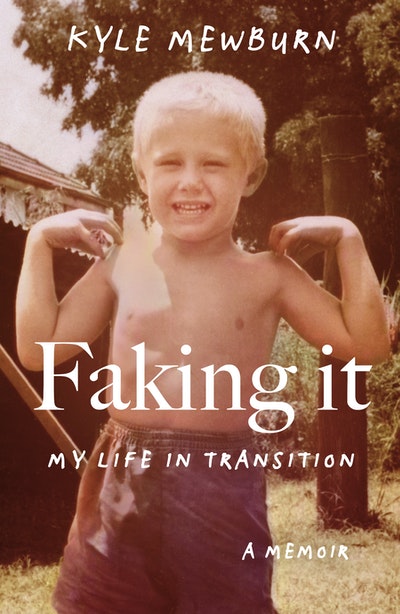

Faking It

My Life in Transition

Extract

I open my eyes. Faces hover overhead, distant. I blink the world into focus. I am in the operating theatre. Of course. With awareness, comes a flicker of panic. Why had they halted the surgery after a few brief moments? 'It is over,' a smiling face informs me.

As my muddled brain deciphers their meaning, relief floods through my body. It is over. I begin drifting back into unconciousness. But I'm halted by commanding voices.

'Come, you must help us. Wake up. That is good.'

I feel bewildered, yet lucid enough to obey. I wriggle myself onto the gurney. An eye blink later I drag myself onto my bed.

A young guy, employed by the company to stay with me and act as interpreter, introduces himself. I don't remember his name. He applies an icepack to my face, then I plunge into sleep.

An alarm jerks me awake. It takes a few seconds to remember where I am. The interpreter's face looms over me.

'I must replace the icepack every two hours,' he explains. He gently peels the limp plastic from my face. My face flushes with a pleasant numbness as the coldness of the fresh icepack washes over me, wafting me back to sleep.

Another alarm intrudes into my conciousness. I glance sideways. The interpreter is sleeping on the other bed. He stretches himself awake and wanders off in search of another icepack. I am more lucid already.

The icepack is replaced. It's not as cold this time. As the night wears on, my periods of wakefulness extend. I am a lot less groggy than I expected. I lie awake contemplating my life. I feel impatient to go home. Back to Marion. I realise the interpreter is swapping between two icepacks. The two-hour interlude is hardly long enough to restore them to full frozenness.

Then darkness slurps me into itself once more. My sleep is dreamless. Death with breath.

I awake again with a warm icepack sitting on my face like a dead jellyfish. I yank it off and look at the interpreter. I could wake him, but decide to wait until the next alarm. Dawn is beginning to filter into the room. I can hear birds and distant traffic.

A nurse comes to check my signs and enquire whether or not I've peed. This seems to be important. I normally drink a litre of water a day, but have been forbidden to have any liquids the last 24 hours, so peeing seems a bit of a tall order.

The morning lightens around me.

The nurse returns an hour later. I meekly confess I have once again failed to urinate. She seems annoyed. I guess they can't release me until I've peed and they need the room. She gives me a glass of water then sternly presses my bladder.

It does the trick. I peel the tepid icepack off my face and glance at the interpreter. He's snoring loudly in the neighbouring bed. I know I should summon him to assist. That's what he's being paid for. But he hasn't been especially helpful or friendly, so I can't be bothered. I slide out of bed and gingerly stand. I've never been under general anaesthetic before, so I'm prepared for anything. There's no vertigo or drowsiness. In fact, I feel incredibly stable.

I set off towards the bathroom. The wheels of the drip-stand lock. I lift it and, holding it before me like a staff, shuffle past the snoring interpreter. I'm surprised how fit I feel. How normal. Apart from my head, which feels like an overfilled balloon.

When the nurse returns I'ma ble to honestly report a successful visit. She accepts my assurance without question and scribbles on my file. I sigh ruefully. If I'd lied earlier, I might be home by now.

A young woman breezes into the room. She chats briefly with the surly interpreter who has only just roused himself. With a final shrug, he departs. The woman introduces herself as my new interpreter. She is bubbly and full of conversation. She is from Portugal and is studying music in Buenos Aires. Casual chaperoning and interpreting help pay the bills. It's the perfect distraction from my growing impatience.

A white coat appears – it;s the surgeon who re-made my nose. His bedside manner is smooth, his English polished. He gently removes the casing, considers my nose from every angle.

'Perfect,' he says, allowing no room for a doubt.

He is affable and precise. He tweezers a 50-centimetre long tapeworm of blood-soaked padding from each nostril with elan. 'I'm magician!' he quips.

A light protective cast is placed over my nose, and my face is bandaged for the journey home. Don't want to scare the natives. I'm now less Frankenstein's monster and more invisible man . . . woman, I mean.

At last I have my get-out-of-hospital-card. Amanda is summoned and an hour later I am discharged. I'm looking forward to getting back to the apartment – back to our little sanctuary. Amanda has arranged for a driver, but there's no phone reception. She leaves me in the waiting room with the interpreter and heads outside to make a call. I try to message Marion, but my internet access has vanished.

It's impossible to know for sure how long we wait. I don't have a watch and there's no point getting out my phone. Amanda and the interpreter make small talk, but my face is swollen I can hardly speak. It's a relief when our ride arrives. We wander into sunshine.

I don't meet the driver's gaze as I slide into the back seat. I'm not being rude, I'm just too focused on not bumping my head. The car looks like it's held together with tape and optimism. The driver speeds like we're being pursued, or as though he's concerned inertia will encourage the car's disintegration. We roar down the quiet, tree-lined avenue and barge into the main-road traffic. It's four lanes each direction, though lanes have only a theoretical value on Argentinian roads. As we weave in and out of traffic, the driver maintains a dramatic monologue, pausing only for breath or to offer honking advice to fellow motorists.

We finally arrive outside our apartment. Amanda hands over a wad of notes to the driver, then eases me out of the car. Marion peers over the balcony. She waves, but I am too tired to wave back. I am bone-tired. A walking statue.

Marion rushes to kiss me and I recoil. My new face is uncharted territory and the numbness makes me hesitant. It's impossible to gauge sensitivity or be sure which bits are safe to touch. Marion's exuberance is often unwittingly dangerous. Better to be cautious. Concern and relief waltz with uncertainty across her face. We drift onto the sofa and she squeezes my hand while Amanda explains my care procedures and painkiller regime. It's not quite the homecoming I'd imagined. I'm too tired to even try and join the small talk or offer Marion many reassurances. It takes too much effort to even open my jaw against the strain of the compression mask.

I offer no excuses as I stand and head towards the bedroom. My bed is a magnet. I detour to the toilet and pass the full-length mirror in the adjoining hallway. I pause long enough to blink at the battered stranger considering me with a passive, unmoved stare. Then slide past. Marion fluffs my pillows. I have to sleep with my head raised for the next few days to help the swelling. I swallow antibiotics and painkillers. A new icepack is strapped over my face in a Hannibal Lecter parody. I feel like the least dangerous person in the world.

The painkillers are doing their work. I feel pressure and discomfort but no pain. The world is distant. Muffled. Of no consequence. I slip beneath the sheets and sleep ensnares me, dragging me back into the welcome oblivion.

Faking It Kyle Mewburn

Candid, funny and emotionally powerful, this is writer Kyle Mewburn's true story of growing up transgender.

Buy now