- Published: 21 January 2019

- ISBN: 9780241975367

- Imprint: Penguin General UK

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $30.00

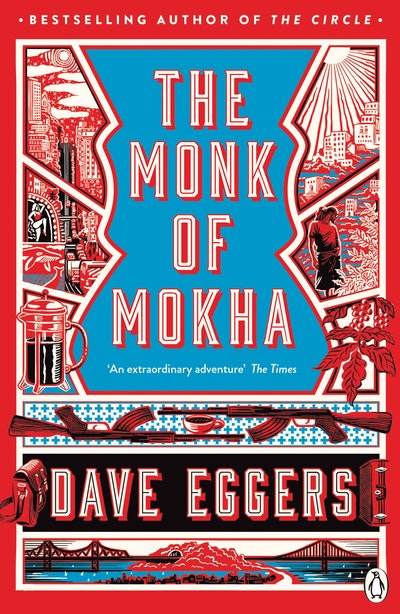

The Monk of Mohka

Extract

Things were clicking into place, Mokhtar thought. He had finally saved enough money to enroll at City College of San Francisco and would start in the fall. After two years at City, he’d do two more at San Francisco State, then three years of law school. He’d be thirty when he finished. Not ideal, but it was a time line he could act on.

For the first time in his academic life, there was something like clarity and momentum.

He needed a laptop for college, so he asked his brother Wallead for a loan. Wallead was less than a year younger—Irish twins, they called each other—but Wallead had things figured out. After years working as a doorman at a residential high-rise called the Infinity, Wallead had enrolled at the University of California, Davis. And he had enough money saved to pay for Mokhtar’s laptop. Wallead charged the new MacBook Air to his credit card, and Mokhtar promised to pay back the eleven hundred dollars in installments.

Mokhtar put the laptop in Miriam’s satchel; it fit perfectly and looked lawyerly.

Mokhtar brought the satchel to the Somali fund-raiser. This was 2012, and he and a group of friends had organized an event in San Francisco to raise money for Somalis affected by the famine that had already taken the lives of hundreds of thousands. The benefit was during Ramadan, so everyone ate well and heard Somali American speakers talk about the plight of their countrymen. Three thousand dollars were raised, most of it in cash. Mokhtar put the money in the satchel and, wearing a suit and carrying a leather satchel containing a new laptop and a stack of dollars of every denomination, he felt like a man of action and purpose.

Because he was galvanized, and because by nature he was impulsive, he convinced one of the other organizers, Sayed Dar- woush, to drive the funds an hour south, to Santa Clara, that night—immediately after the event. In Santa Clara they’d go to the mosque and give the money to a representative of Islamic Relief, the global nonprofit distributing aid in Somalia. One of the organizers asked Mokhtar to bring a large cooler full of leftover rooh afza, a pink Pakistani drink made with milk and rose water. “You sure you have to go tonight?” Jeremy asked. Jeremy often thought Mokhtar was taking on too much and too soon.

“I’m fine,” Mokhtar said. It has to be tonight, he thought.

So Sayed drove, and all the way down Highway 101 they reflected on the generosity evident that night, and Mokhtar thought how

good it felt to conjure an idea and see it realized. He thought, too, about what it would be like to have a law degree, to be the first of the Alkhanshalis in America with a JD. How eventually he’d graduate and represent asylum seekers, other Arab Americans with immigra- tion issues. Maybe someday run for office.

Halfway to Santa Clara, Mokhtar was overcome with exhaustion. Getting the event together had taken weeks; now his body wanted rest. He set his head against the window. “Just closing my eyes,” he said.

When he woke, they were parked in the lot of the Santa Clara mosque. Sayed shook his shoulder. “Get up,” he said. Prayers were beginning in a few minutes.

Mokhtar got out of the car, half-asleep. They grabbed the rooh afza out of the trunk and hustled into the mosque.

It was only after prayers that Mokhtar realized he’d left the satchel outside. On the ground, next to the car. He’d left the satchel, con- taining the three thousand dollars and his new eleven-hundred-dollar laptop, in the parking lot, at midnight.

He ran to the car. The satchel was gone. They searched the parking lot. Nothing.

No one in the mosque had seen anything. Mokhtar and Sayed searched all night. Mokhtar didn’t sleep. Sayed went home in the morning. Mokhtar stayed in Santa Clara.

It made no sense to stay, but going home was impossible.

He called Jeremy. “I lost the satchel. I lost three thousand dol- lars and a laptop because of that damned pink milk. What do I tell people?”

Mokhtar couldn’t tell the hundreds of people who had donated to Somali famine relief that their money was gone. He couldn’t tell Miriam. He didn’t want to think of what she’d paid for the satchel, what she would think of him—losing all that he had, all at once. He couldn’t tell his parents. He couldn’t tell Wallead that they’d be pay- ing off eleven hundred dollars for a laptop Mokhtar would never use.

The second day after he lost the satchel, another friend of Mokhtar’s, Ibrahim Ahmed Ibrahim, was flying to Egypt, to see what had become of the Arab Spring. Mokhtar caught a ride with him to the airport—it was halfway back to his parents’ house. Ibrahim was finishing at UC Berkeley; he’d have his degree in months. He didn’t know what to say to Mokhtar. Don’t worry didn’t seem sufficient. He disappeared in the security line and flew to Cairo.

Mokhtar settled into one of the black leather chairs in the atrium of the airport, and sat for hours. He watched the people go. The families leaving and coming home. The businesspeople with their portfolios and plans. In the International Terminal, a monument to movement, he sat, vibrating, going nowhere.

The Monk of Mohka Dave Eggers

From San Francisco to Yemen, the gripping true story of a young American immigrant and his quest to resurrect the ancient art of Yemeni coffee - while escaping a terrifying civil war

Buy now