- Published: 4 April 2023

- ISBN: 9780143777618

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $40.00

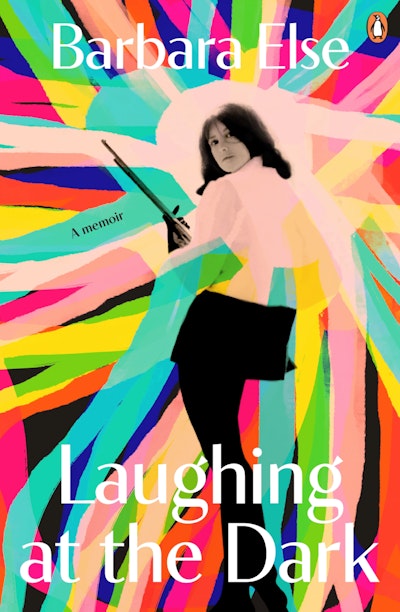

Laughing at the Dark

a memoir

Extract

1

green

nectarines

Laughter. I must be less than two years old (I remember the nappy), standing in a kitchen cupboard that reaches from the bench right to the ceiling. My father keeps shutting the door, opening, shutting. Each time it opens I explode into laughter.

My dad is a kind man with a benign sense of mischief. My mother always says ‘Look on the funny side’ if there is a disaster, and there usually is a funny side. Laughing helps to keep things under control.

When people ask me where I come from I hesitate, deciding what to tell them today — the long answer or the short one. Home is a slippery notion, less a geographical place and more an idea of where I shelve my books, arrange my special things like bowls and vases, have my laptop and someone I love. I’ve lived in the South Island — Invercargill, Riverton, Christchurch, Ōamaru, Dunedin. And in the North Island — Wellington, Auckland. During my childhood the changes were announced and carried out with such speed that we seemed to blink and be in a new city, new town, trying to fit in. It would be hard at first, I would grow to love each place, then be whisked off again. It was a case of ‘follow the man’s job’, and we children were the tag-alongs.

My first memories — the laughing in the cupboard days — are of Riverton where we live on a hill across the river. I have a sense of being an observer: huge sky, Foveaux Strait, the estuary, fishing boats, the village on the far side. My brother and sister, the twins, are eight years older than me, each with blue eyes, but Tom has curly hair, Tardi has straight.

Our house is up a steep path. My skinny Granny Groves rushes me down then up many steps to the neighbours who have a phone, such a rare thing. I’m laid on a settee in the sunporch. A doctor looms over me, peering closely. Behind his shoulder are the upset faces of Granny Groves and the neighbour with an apron tight over her plump bosom. I’ve shoved a bead up my nose.

How silly they are to be worried, I think. If it went up, it can come out.

I’m sure the bead was blue. But it might have been red. Who can trust what they remember? Why should such a tiny drama even stay in my memory? Maybe it was the first time I could clearly think What silly grown-ups. Maybe I just enjoyed any small drama, as little ones do, like the bus trip into Invercargill.

Nearing Gala Street my mother says, ‘Barbara, watch for the cat.’ I kneel on the bench seat and see the concrete cat high on a tile roof. It’s midprowl, eyes on a concrete bird down by the gutter. The bird is perpetually safe. The scene is the very satisfying middle of a tale.

Dad, George Pearson, six foot one-and-a-half, slim and handsome, bald since his twenties, is a man of principles. He tends not to visit them on other people, though once he hit the back of my leg with a doubled-up rope. I’d wagged Sunday School, fed up with being good about it week after week, and coaxed my little sister, Lesley, to hide with me in the long grass of the empty section across Landscape Road in Mount Eden.

He didn’t ask why I’d done it, which annoyed me more than the welt on my calf. My answer would have been — I might even have used these words, at ten years old — I’ve heard the Bible stories over and over, the Sunday School songs are even more boring, with predictable sentiments and tedious tunes. I was packed off to bed for the rest of the day, and was happy to stay there surrounded by books. Poor Lesley had to go to church with him and put her Sunday School penny in the collection plate when she’d been hoping to spend it on sweets.

But when it comes to himself, Dad can see the funny side.

One evening when I’m at high school I wait for him on the Jean Batten Place corner opposite the National Bank, where he’s an Assistant Manager. The heavy door swings open. Though it’s very late, the man who steps out must be a customer. The suit has baggy knees, the grey fedora’s on the back of his head. I glance away, then look again.

Of course it is Dad. He never tilts his hat to a city-smart angle.

We bus home together.

‘Did you have to wait long for him?’ asks Mum.

‘I thought he was a cow cocky come to town,’ I say, and they both laugh.

The key thing about Dad is that he respects women and admires them. He has no doubts that what they do is valuable, in or out of the home.

Mum, Dorothy Pearson, née Groves, usually in a gingham apron, is slightly bigger than pint-sized, blue-eyed with permed brown hair. After the first year of a BA she decided to study for a Teaching Certificate as well. Back in the 1930s she had to ask the university for permission to do both at once. Her supervisor said to this young woman who was captain of a hockey team that she was too frail, and he refused.

Huh, she thought, I’ll do it anyway and won’t tell him. She was the first woman at Otago to graduate with a BA and a Teaching Certificate in the same year. A fine role model for quietly refusing to do what you’re told.

Dad urged her to continue with university and get an MA. Mum said no, she wanted to start a family and take care of the children. When Dad was finally called up for World War Two, married women weren’t supposed to get a teaching job. Mum applied for one under her maiden name. After all, she had twins to feed — Tom and Tardi who were born in 1939. (My older sister’s real name is Dorothy, but when they were little Tom tonguetwisted it to ‘tardi’ and it stuck.) And Mum’s own mother, Granny Groves, was available to live with her and take care of the children.

Mum dresses for Lions Club dinners in rustling taffeta, and for the Bank Ball in red velvet with a silver glitter. Once a month she plays Mahjong with friends. She has her cards read now and then by Rita, another Bank Wife. Mum is certain that what Rita sees in the cards sometimes comes true. In other respects, Mum is the essence of practical.

Just after I become engaged when I’m twenty-one, Rita reads in the cards that someone close to Mum has made an expensive purchase that could turn out to be a disappointment. ‘I hope it’s not that ring,’ Mum says to me. Of course it won’t be, I think, how ridiculous.

Mum is a contradiction. Her own parents used to have terrible arguments and she’d sworn she would never get married. Then she met Dad and decided she would marry but would never argue. And she never did. That’s her thing — the iron will. The kindness but the clamping down on difficult emotion. ‘See the funny side’ is often said through her clenched teeth.

Laughing at the Dark Barbara Else

‘My own first memory is the cupboard door, and laughing, erupting with laughter’ - a memoir about finding an identity, a voice and laughter.

Buy now