- Published: 3 September 2018

- ISBN: 9780143771562

- Imprint: RHNZ Vintage

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $38.00

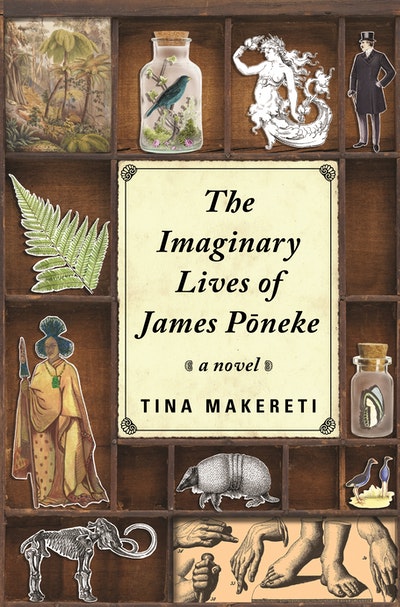

The Imaginary Lives of James Poneke

Extract

CHAPTER ONE

I am not yet seventeen years of age, but I have a thought that I may be dying. They don’t say that, of course, but I can read it in their many kindnesses and the way they look at one another when I speak of the future. Perhaps I do not need their confirmation, for surely I wouldn’t see all I can in the night if I weren’t playing in the shadow of death. So when they come and ask about my life, I tell them all. What else is there for me to do? I don’t feel it then, the brokenness of my own body. I feel only the brokenness of the world.

CHAPTER ONE

I am not yet seventeen years of age, but I have a thought that I may be dying. They don’t say that, of course, but I can read it in their many kindnesses and the way they look at one another when I speak of the future. Perhaps I do not need their confirmation, for surely I wouldn’t see all I can in the night if I weren’t playing in the shadow of death. So when they come and ask about my life, I tell them all. What else is there for me to do? I don’t feel it then, the brokenness of my own body. I feel only the brokenness of the world.

From here, in the shadows, I can see a piece of London’s sky and the roofs of countless houses. The curtain is flimsy, and I have asked Miss Herring to leave it aside, for I am so high in this room and the sky is my only companion these many hours. At night, I see the beetle making his slow, determined way between cracks. I smell the city rising then: black smoke, the underlying reek of piss and sweat, the sweetness of hung meat and fruit piled high in storage for the morning, its slow rot. My own. The street waits, and the beetle crawls, leg over leg, down the brick side of the house. From his vantage point, I see it all: every detail in the mortared wall, the coal dust that covers it; the wide expanse of London Town, lights shimmering along the Thames and out into a wide panorama more delightful than even the sights of the Colosseum. I wish I could tell you the air is fresh here, but no, it is stench and smoke and fog rising, obscuring the pretty lights. Yet I love it, love this dark and horrid town, feel the awe rising even beside the dread. It is a place of dreams.

Sometimes I follow the moth who finds her way on swells of air, a ship catching currents established lifetimes ago, knocked sideways by the draught of a cab passing, the hot air expelled from a gelding’s nostrils. The moon is different here, not a clean, clear stream, but a wide and silty river. She lends her light all the same, so that I might see the faces that pass. And they pain me, it’s true, for every face is one I know, and I cannot say whether they are living or dead. I see all the misses and misters of the streets of London, and the ones of Port Nicholson. The worst of it is when I see the tattooed face, or hear the music of the garden orchestra, see gaudily dressed couples dancing circles, the spectre of shows pitching illusions into the air: tricks of light, mechanical wonders, wax figures bearing features I knew only for the first few years of my life. I couldn’t even remember my mother’s face until I was confined to my bed, and now I see her every night, a doll animated by a wind-up box. The acrobats then, and my friends from the card table. Warrior men and women of my childish and dark memories, from before I learnt about the world of books and ships. My shipmen, both loved and feared. They don’t speak, my friends and enemies and loved ones, but I know they are waiting; I know the streets below are teeming with them, even when the hour grows late and all decent men should be in their own beds.

It is as if I travel through all the old battles each night until I reach him, and though I know not whether he still walks the solid Earth, I always find him. Billy Neptune, even now grinning and ready to make fun. He is the only one who sees me.

‘Hemi, good fellow,’ he calls, ‘back to your bed! What is your business out here amongst the filth of the streets? Not the dirt, mind you, I mean people like us!’ At this he laughs his short, booming laugh, a sound that breaks open in my chest like an egg spilling its warm yellow centre.

‘What is it like?’ I ask him every night, or, ‘How are you?’ But he doesn’t answer.

‘Ah, Hemi,’ he says. ‘What games we made of it, eh, my fine friend? What games.’ And he goes on his way, and I go on mine, circling the restless world.

These past few nights I seem to have gone further than before, and this morning Miss Herring commented that I looked more tired than I had yesterday, when I had seemed more tired than the day before.

‘Are you not recovering, Mr Poneke?’ she asked. ‘Should I ask Miss Angus to bring the doctor again?’

The doctor has been three times already, and though he works his doctoring skill on my body, I’m afraid he does not have medicine for what ails me.

‘No — all is well, thank you, Miss Herring. Only, I do not seem to sleep at all, and travel the world in my imagination through the long night instead. It seems as real as you standing right here this morning.’

The maid shook her head and smiled, as she always does when I use her name, for I am the only one who addresses her formally, and no one has yet found a way to correct me in this habit.

‘Mr Poneke, I believe you’ve travelled to the very ends of this Earth. You must have many memories of adventures beyond what’s normal.’ She hummed as she made to clean the fireplace and reset the fire. I suppose Miss Herring and I enjoy an uncommonly open interaction, one that she would not enjoy with more formal masters. But I am not a master, and my position in the house has always been unusual, and I have a great need of companionship, spending so much time alone in bed as I do.

‘It is a dark night I go out in, and I am liable to see ghosts.’

At this she drew in a sharp breath and blustered about, leaving as soon as she saw Miss Angus arrive with the soup she brings each day. Miss Angus enquired after my health, and I repeated what I had told the maid, save for the part about ghosts.

‘Sometimes I wonder — if I had a way of telling my story, perhaps it wouldn’t haunt me so. What think you, Miss Angus?’

‘It seems like as fine a way to pass the time as any.’ Miss Angus sat with her sewing in the chair she’d set up by the window for such a purpose. She is endlessly patient with me, endlessly considerate. It is a comfortable room, and easy to talk. And so I did, describing how only three nights before I had begun to leave the London of my dreams. I was tired of all the shadows of the city, I said, thinking of my personal ghosts. Instead of my usual wandering I sped to the wharves, and there I took a ship and walked among the men as they worked. I did not tell her that all my ghosts found me on the ship, that I had simply moved them along with me. These crews of my old life took me over the oceans, faster than ever before, until we were again in Barbados.

From there, each time Miss Angus came to attend me, I told her of a different night’s travel. Sometimes we stayed aboard ship, or were tossed again in the wreck of the Perpetua; other times we returned to my wandering days in New Zealand. Despite never straying from the tasks in front of her while I spoke, Miss Angus seemed serene and even entertained by my foolish stories.

After a week of such adventures I feared I may have confused Miss Angus with all my tales of roving about the world. I hadn’t told them in any sort of order — it does not happen that way in the telling of a tale, and it is hard to keep my mind straight when my existence is so still. Time makes its own game when life is so slow and painful, my entire world now nothing but this bed, four walls and window. I cannot even rise to relieve myself, and so all modesty goes out that window with my mind, though I find the telling alleviates the dreams somewhat. Occasionally Miss Angus frowns and asks where this or that island is, what I mean by a foreign word or shipman’s phrase. My descriptions are of no use to her, I fear. She has no reference point beyond the river, no experience of the world beyond London’s centre. The strangest place for her might be the land of my birth, which had no grand buildings, no trains, no exhibition halls or galleries, no palaces, barely a newspaper or carriage when I left it. I was just a boy, half wild and fully lost, and the world around me an unmapped forest. I knew there was trade and ships — of course I knew that — but I could not imagine this world that seems to be made up almost entirely of those things.

In my earliest memory there is green everywhere, leaves and leaves of it in a great pile, my mother working beside me, and, when I look up, more. It is the wide umbrella of the ponga tree I see, its many brothers and sisters encircling us. A kind of speckled light is thrown over everything as it breaks through gaps in the trees’ canopy. My mother works the flax until it is soft, and folds it into her many layers. I cannot tell you what it is that day. Often she made whariki — the mats we used to line our homes or sleep upon. Or kete — those were quick and easy to make, and sturdy, for gathering our food or carrying things from one place to the next. Some long winters were spent working at a cloak — I remember this because the muka fibres were so fine and I was not to touch them even though she let me play freely with the broad green leaves before they were stripped down to soft strands.

No, this day it must have been a kete, something easy and light, I think. It must have been warm, for I remember no cloth or cloaks hindered our movement. Even so, the undergrowth smelt like wet dirt and rotting leaves, the kind of smells that signal not decay but new growth. It was my game to imitate my mother’s work by lifting and folding leaves one over the other, though mine did not stay together or transform into a whole as hers did. Even Nu, my sister, tried to help, but I had more game than goal in mind, so my failures gave me as much pleasure. When I wandered away she came after me, calling in a high voice, or scolding when I took too long. She tried to work at her own weaving when I was settled. Sometimes kaka parrots came down to make off with our scraps. Sometimes tui birds yodelled at us like singers from the opera. We talked to them as if we knew their language. Perhaps we did. It was just the world. We listened and tried to call back, my sister entertaining me with her imitations while our mother worked.

I do not know how old I was, but I cannot have been more than four or five. Everything for me was sight and sound and flavour, the grubs beneath as fascinating as the pretty leaves above. The forest litter, rot, all of life. The delicious squirming and leaping of my small-child’s body. Our simple entertainments. Sometimes we wandered away to join the other children while our mothers worked together. Nu was my constant companion; I couldn’t tell you her proper name now. If I was hungry she found a morsel for me to eat, some dried fish or meat from the night before, fern root to chew. She never let me out of her sight.

I remember all this because what came after was so sudden and preceded by such stillness. It was the birds who first went quiet. Nu was dangling from the branch of a tree overhanging a little creek we liked to play near. All of us children were making our noisy way across, and my sister thought she might do so without touching the water. I tried to copy but fell to the riverbank, then pretended I was happy to watch her swing above, almost as if she could touch the tops of the trees. Looking up, always looking up at my sister.

At first we didn’t know what was missing. We were being loud enough for our mothers to hear us, and the sound of nothing came over us slowly, swallowing our voices one by one until we too were silent, straining our ears, listening.

I don’t know how long that moment of silence was, but when I think back I am suspended there. Everything slow and quiet and wrong. Then a loud noise came in, a sharp cry that shattered the still. Sound rushed towards us then, our mother’s cries: ‘Tamariki ma! Rere atu! Come away now!’ All of it at once — scooped into my mother’s arms, but where was Nu? Where was Nu, my big sister? And my mother ran and ran and put me down under branches and then there were the sounds of weapons on flesh, and something else, too, sharp and so loud it sounded like the world had split in two. I stayed hidden because I was small, and silence had now been pushed into me and planted there. And no one saw me even though my mother lay down and looked right at me. She couldn’t see me, though. I understood this when she looked and looked until her eyes became clouds.

I woke to Miss Herring stoking the fire again, and bustling about the room as if the fire had been set under her own petticoats. ‘What is it, Miss Herring?’ I asked, and she made a hmph sound that seemed to be another way of saying I had done wrong.

‘It may not be my place to say,’ she said eventually, not looking directly at me. ‘But you must watch what you say to Miss Angus now. She left this room in quite a state this afternoon.’

‘Oh dear. I seem to have got carried away. Maybe I shouldn’t speak so freely.’

‘Of course you must, Mr Poneke — speak freely, that is. But these are not always things for delicate ears, are they?’

‘No. Quite. I will not speak of it again.’

The maid stepped towards the door, then back again, swaying like one of the great animals in their cages in the zoo and getting redder in the face as if she fought some internal battle concerning her thoughts.

‘Please, Miss Herring . . .’

‘Mr Poneke.’ Miss Herring is a year or two older than me, but she speaks as if I am her senior. ‘I think it is good for you to . . . unburden yourself, so to speak.’

‘But, as you have shown, my words are offensive to Miss Angus’s ears.’

‘Perhaps she was only unprepared, or perhaps you might watch how much you say in the unburdening.’ Her countenance had relaxed somewhat. ‘I may have an idea, if it’s not too bold.’

She didn’t allow me to respond before she was gone.

The next time Miss Angus came she brought paper and ink and fresh quills. Of course I had a small supply, but she must have procured some fresh for this purpose. I was to write my burden down. Miss Herring had suggested it, and she’d agreed. It would exercise me, and give me something to do.

I had not so much as lifted a hand since I’d been brought back to the house, and I had to agree the time for idleness was over.

And Miss Angus asked that, when the time came, I might sometimes read my writings to her while she sewed or mended. She might be shocked, I warned her. There were things I could hardly believe and wanted to forget myself. To which she answered she had seen a preserved two-headed monkey at the Egyptian Hall when she was just eleven, and a woman swallow swords and fire when she was fourteen. Worst of all, she had heard the tales of two hangings from the cook when she was a child and she knew the world was simply full of such horrors, which was why we should put our faith in the sweet Lord to keep us safe and sane. Besides, I could always keep the worst to myself, since I now had the paper to keep it.

I did not feel adequately endowed to argue with this.

I will write to you, my future, and sometimes I will write to the ones who look after me here, and sometimes to the ones who have passed on. If I try always to write for Miss Angus, everything will have to be genteel and kind like her, but my life has not been that way. As I tell you about the land of my birth it will, I know, seem like a picturesque scene to you, for it seems that way to me now, and I do not know whether it is the Artist’s pictures that throw shade on my memories, or whether it really was that pretty. My earliest memories certainly do seem green and innocent. It is something to hold on to that any time in one’s life is so. The sound of guns put an end to all that.

My father was a chief. I did not know this when I was an infant hiding under a bush. After the quiet came again, sometime after, when hunger gnawed away at me but silence still kept me hidden, I heard the sound of men coming through; I heard them calling in rough voices that turned soft too quickly when they found us.

‘Mihikiteao! Nuku? Hemi? Aue, hoki mai koutou!’

Hemi was my name, I knew that, and so I peeked out. As soon as I moved, great arms came down and lifted me around my stomach, and I vomited in fear. But the arms took me to the man I knew as Papa, and he wiped me clean and held me. ‘Taku tama,’ he said. ‘Taku potiki.’ And I knew these were his tender names for me. The man who had brought me now showed my father where my mother was, and he held me close and shook, with sadness or rage I could not know. I was so frightened I retched again, but nothing came out.

Later we found Nu, and she could no longer call to me; she would no longer watch over me. The men buried the women and the children. And I stood at the graveside, mucus and tears running down my face and into my mouth.

My father took me with him, but I was too small to keep up, and I imagine I must have been too burdensome for the men to carry as they searched the land for the murderers of my mother and sister. I was with them only a few days before my father found some people for me to stay with. We came upon a white house on our own lands, and my father said it was the Missionary House and I would be looked after there, and I remember nodding solemnly and with great importance as if I knew what this meant. It was only when the people came out of the house that I gasped and shook and ran to hide behind my father’s legs, for they were the first white people I had seen.

‘These are my friends, Hemi,’ my father told me. ‘They have been great friends to your father, and they will be great friends to you.’

I heard these words, but I couldn’t move. The people looked sick, their colour gone. Could they see from those eyes? What shape were their bodies under the strange clothes? Where were the ladies’ feet? I rested my forehead against the back of my father’s patterned thigh and peeked out from behind him. I remember I felt hidden, my arms wrapped around his leg, even though some part of me knew I could be seen. It did not matter, he would protect me forever, I thought, but my father’s legs never stopped moving, and I could not stay in their shadow much longer. He pushed me forward.

‘You will be safe here, taku tama. If I leave you with our people, who knows what may become of you? These Mission people are not part of our fight. They bring solace with their Christ and their wonderful things. Look at the cow! Look at the butter churn! You will learn here, and when it is all done I will come back for you.’

I did not know what ‘cow’ or ‘butter churn’ were then. Can you imagine? But my father had gestured towards a big animal on four legs like a kuri, and even though she had terrifying proportions and sharp-looking growths on her head, she had the softest, biggest eyes I had ever seen. I did not know what the churn was, but white people and cows were quite enough learning for one day. I had no inclination to get closer to either of them.

I was a small, half-naked child, and it was easy enough for the missionary lady to take me by the hand and for my father to leave swiftly with his men, and for the world to seem emptier than it ever had. Where were the trees? Where were the birds? All around the house was cleared, though a wall of forest encompassed the place. This was my new home, then, and I was too exhausted to fight once Papa was gone. They took me and washed me and put me in white people’s clothes. I had never been so uncomfortable in my life, everything held and bound and scratching against my skin. For weeks I would wander as far as I could from the house, and they would find me with my clothes half off and half tangled around my limbs. But the white men’s clothes were too ingenious for me to engineer an escape until I was already used to them.

After that my father would come whenever he could, which was not often. He was my sun. His arrival signalled for me a glorious break in the tedium of mission days. But whenever I saw him I also thought of my mother as she’d stared at me with no sight, and of the lovely sister who was no longer there to watch over me, and it was like a dark hole opened and I almost tripped into it. I think I feared my father and the feelings he brought with him, even as much as I desired the bright glamour of his company. For he was exciting, my father. He was a presence — physically imposing, yes, but more than that. To hear the warm depth of his voice as he spoke his endearments to me was to hear the night talking to the day. I know others were drawn to him too, though the missionaries did their best to keep a pious distance. His arrival was preceded by a heightened nervous energy throughout the Mission — all of us keen to catch a glimpse, or hear stories of his most recent skirmishes. And of course I had an honoured place in all of this, for I was the only one who came within touching distance of his great person.

Sometimes he came to eat with the Minister, and listen to the sermon, but he would not enter the white house. I can see now how important he must have been, for the Minister came out to him and sat with him, even upon the ground. I came to his lap and traced my fingers along the tattooed lines on his legs until I was too old for such intimacies. He coddled me, not even slapping me when I pulled at the hairs and made him wince. But I was not to touch his face. Even I knew that. The moko there fascinated me, and he told me how my ancestors were all in those designs, how every line and curve told the story of our whakapapa, and how this was the most sacred of knowledge, written on his face, written in his flesh and blood and the ink of our land. Papa, how you indulged me, and how I have failed you, for I can no longer recite those genealogies, nor have I earned the right to wear them. I am so far from our whakapapa now, though I know you would tell me it runs in my veins the way the sea runs over the Earth, and there is no distance I could travel to disinherit that which I am. This I know you would say, though I don’t know that I can make myself believe it.

Perhaps you can forgive the foolish boy I was for my fears and insecurities. I pay for them each time I think of you. Once I was finished with the fun to be had on your knee I would be away again playing with the other mission children, safe in the knowledge that you would return, and return again. I was not a true orphan then like the rest. You had serious conversations to have with the adults, and such things bored me, but you were a good distraction for the whole house, and all us children took advantage of it. After service we managed to avoid the chores while the main meal of the day was prepared. There’d be plenty to do later. In the meantime we would run and chase and play stick games and pretend. Most often I got to be chief in our make-believe games, for I was the only one with a parent still alive, and such an impressive one. Except when Maata Kohine decided she was in charge: she had more natural authority than me and was stronger, too.

The only thing that fascinated me as much as your moko, Papa, was the other writing I was learning. You were keen on it too, but it came to me so quickly and I had not the other responsibilities that were your burden. For you did not come back as often as I would have wished, and the tribal battles kept you constantly moving. I didn’t understand that world, except that you wanted me away from it and safe. And you were happy to see my love for the Book, the Word, and the ways of the pen. You said these were implements that would help our people be strong in this strange new world. Now I think that sometimes when you talked like that it was with a mix of admiration and horror. I know this feeling well, especially here in London. I might have even known it then, for though it was weighted greatly towards admiration, that same equation still played a part in my feelings for you. You were a formidable man. You were a fearsome man. Your voice told me you were a gentle man. You were my sun. And then you came no more. If I had known, I would never have left your knee nor lifted my fingers from the tracing of your moko.

The Imaginary Lives of James Poneke Tina Makereti

From an early age, James Poneke has had to play a role to survive. But what of the real James?

Buy now