- Published: 3 July 2017

- ISBN: 9781925324723

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 464

- RRP: $30.00

Albanese

Telling It Straight

Extract

‘She made a decision at that point in time that her life would be lived through me – through a child,’ Anthony Albanese says of his mother. ‘Lots of parents do that but the truth is, it’s particularly women who do that, much more so than blokes.

It’s very selfless.’

When his mother died in May 2002, Anthony told those gathered at her funeral service that she was the finest person he had ever known.

‘A two-person family is different,’ he said, standing before the congregation at St Joseph’s Catholic Church, Camperdown, next door to his primary school, up the road from home and where most of his family’s religious rituals had been performed since before he was born.

Six years into his parliamentary career, this address from such a familiar pulpit was easily the hardest speech of his life.

‘Mum had to not only be a mother but also a father figure, brother, sister and best friend. She was my soul mate. I am so proud to be her son and so fortunate. Mum gave me strength – inspiration – and believed that I could be anything I wanted to be.’

As her coffin left the church, he crumbled with the wail of someone losing a part of himself.

While Anthony was not one of those who claimed lofty political ambition from an early age, Maryanne claimed it for him as mothers often do. She believed he could go far – as far as a person can go in the Australian political system – and she told her close family the same. Anthony’s cousin Norm Howett recalls that his aunt, known by family and some friends as Mary, routinely declared an unfaltering belief in her son’s capabilities.

‘Mary said to me that he would be Prime Minister one day,’

Norm says. She said it more than once – and to others more than to her son himself.

‘Oh, you’re bright enough,’ she would tell him. She was, as Norm puts it, ‘ultra proud’.

In contrast to the close relationship he had with his mum, Anthony knew nothing much of his father at all – just a romantic, tragic story of how he had come to exist.

He knew his father’s name was Carlo Albanese and that he was Italian. Maryanne Ellery had met him on her greatest adventure, a trip to Britain and Europe when she was 25.

The younger Albanese doesn’t remember specifically being told his parents’ story in detail. He just recalls that from when he was young, he’d heard that Maryanne and Carlo had married after a short courtship during her eight months abroad, but that his father had then died in a terrible car accident, leaving his mother a widow with an unborn son.

The story was accepted without question among those who knew it, both within the family and around the neighbourhood – there was no reason to doubt it. And on the subject of young Anthony’s father, that was the extent of any real discussion.

Nobody talked about the issue much at all.

But one night when her son was 14, Maryanne sat Anthony down at the kitchen table and said, ‘We need to talk.’ And then she told him the truth.

It was a startling rewrite of his life’s story.

Maryanne Ellery had, indeed, met Carlo Albanese on her trip to Europe – a four-week ocean voyage she and her older brother, George Ellery junior, had taken from Sydney to Southampton, in early March 1962.

George was an entertainer – a comedian who specialised in impersonations – and he was booked to perform on the ship, along with an American mate, Mel Young. Seeing the chance to travel but not go alone, Maryanne decided to join them.

They travelled on the Fairsky, a cruise ship of the Sitmar Line which was among those bringing out English immigrants under Australia’s assisted migration program. Sitmar was offering cheap fares for the return voyage, to avoid sailing its vessel back empty.

Maryanne saved as much as she could from what she earned as an usherette at a city theatre and headed off to see the world.

They sailed up around the north of Australia to Asia, along the Suez Canal to Europe and on to Britain. Carlo Albanese had been a steward on board. He and Maryanne had begun a romance.

Although Maryanne skated over the finer details in the telling, on the raw mathematics of her son’s birthdate almost exactly a year later, it was clear that her association with the dark-haired Carlo had not ended when the Ellerys disembarked into the British spring that April. For Maryanne, it would be a five-month stay.

The ship sailed between Britain and Australia in a continuous loop, four weeks over, four weeks back, so Carlo Albanese was off again almost immediately, then back in Southampton again two months later. After that next visit, the good Catholic girl discovered she was pregnant.

According to this new version of his origins tumbling out onto the kitchen table, the teenage Anthony heard how Maryanne had told Carlo of her situation. The response was not what she might have hoped.

He had explained that he could not marry her. He was engaged to wed a girl from his town in southern Italy and that was what he was duty-bound to do.

So, contrary to the story upon which he’d built his life to date, Anthony learned that his parents had never actually married at all. There had been no accident and probably no death.

Still a single woman, Maryanne had arrived back in Sydney in October of 1962, seven months overseas and now nearly four months gone.

She moved back in with her parents and acquired and wore wedding and engagement rings – to this day her son doesn’t know where they came from – and took her lover’s surname as her own, not bothering with the deed poll.

When her son arrived on 2 March 1963, he became Albanese too – pronounced in a plain, Australian way without any Italian flourish: Alban-eez.

She named him Anthony, after his late cousin, Anthony Howett, who had died in a car accident, killed by a distracted driver on the Pacific Highway in northern New South Wales, four years before. The first Anthony was the son of Maryanne’s beloved eldest sister, Veronica, known as Ronnie.

In 1959, Ronnie and husband Arthur Howett bought land on the highway at Halfway Creek in northern New South Wales. They built a service station and were adding motel units to the complex when the accident happened.

An impressive semi-trailer rig had pulled up on the other side of the highway and Arthur decided to cross the road with his three youngest children to have a look. As he hoisted baby Shirley into his arms and six-year-old Helen took the hand of her four-year-old brother Anthony, a car rounded the bend, swerved and hit the little boy. Through the service-station window, his mother saw her son tossed into the air and then run over.

The family’s eldest child, Norman, was away at boarding school in Yamba but can describe it as if he was there. ‘Mum watched the whole thing,’ he says.

Their accommodation units became known as Anthony’s Motel.

Maryanne did her best to comfort her grief-stricken sister and when her own boy was born four years later, she named him for his departed cousin, choosing Norman as his middle name.

The death of the little boy would haunt the family. Many years later, the imprint of it would make his namesake, by then the federal Transport Minister, extra passionate about duplicating that deadly stretch of road.

After her own Anthony was born, Maryanne had gone about her life in an elaborate, well-intentioned ruse.

Seeking to avoid the innuendo she feared might come from being an unmarried mother in a tight-knit working-class Catholic community in 1960s Sydney, she presented herself to the world as a young widow, to protect her son from scorn and maintain their family’s public reputation.

Sitting there in the kitchen with her teenage son that night, Maryanne was concerned about how Anthony would react to the extraordinary secret she had just revealed.

It was a lot for the 14-year-old to take in and although he doesn’t know why she chose that particular time to tell him, she had clearly waited until she thought he was old enough to absorb it.

She feared he might be angry or worse.

‘She, I think, was petrified somehow that I’d . . .’ he pauses, searching for the right word. ‘Not reject her . . . but that it would change our relationship.’

He told her it wouldn’t and that he was neither embarrassed nor upset by her revelation. But it was clear that finally revealing what she had kept from him for so long was emotionally difficult for his mum.

She asked if he felt he was suffering by being in a single-parent family. And she wondered aloud if he would like to try to find the father who, suddenly, strangely, might have come back to life.

But the hard-edged teenager wouldn’t hear of it. He felt his father hadn’t cared for him enough to even contact him, so why would he want to go looking?

‘I do remember at the time saying “I’m not interested”,’ he says. ‘And I do know that that’s what she wanted to hear.

What she needed was for me to say, “You’re all I needed.” ’

And he insists she was, so it wasn’t hard to say it. He was her son; he loved her and she him. And that was enough.

That was pretty much where they left it. It meant that was also where he left it for more than 30 years.

Although Anthony tried to steer her back to the issue a few times when he was much older, Maryanne didn’t add a lot to the sum total of his knowledge of his father or where he might be. Naples featured in her responses now and then, but, frustratingly, details were scarce.

As he grew up, he listened carefully as she dropped snippets into conversations with his closest friends about life and the world. But they were contradictory and confusing.

She wasn’t deliberately being unclear, he knew that. By then, the many years of pain from chronic rheumatoid arthritis and its associated pharmaceutical treatments had simply taken the edge off her memory. But he couldn’t be sure anymore what was true and what was embellished for the sake of the storytelling.

He didn’t blame her for that but it bothered him a bit because in trying to sort out what was real and what wasn’t, it didn’t help.

Except for those occasional mentions, the brief and intensely personal talk at the kitchen table was the only time in his life that Anthony Albanese and his mother ever discussed the truth about his parentage directly, in any detail.

Anthony’s lack of desire to find his father would remain largely unchanged for as long as his mother lived. Though he would sometimes wonder about Carlo and try to draw together in his head the fragments of things Maryanne said, he never did anything about it.

He insists he didn’t suffer for the absence of a dad.

‘It’s the opposite of Joni Mitchell,’ he says, referencing the Canadian singer’s hit ‘Big Yellow Taxi’ and its famous line about not knowing what you’ve got till it’s gone. ‘You don’t know what you’ve lost if you’ve never had it.’

Any curiosity he might have had about his father was always countered by the feeling that, somehow, he would be doing wrong by his mum to pursue it. It wasn’t quite a sense of betrayal – it was something else.

‘Discomfort,’ he says. ‘I didn’t want anything to cause her discomfort.’

So for decades, he left his family history right where it lay.

His friends believe it had to have weighed heavily on him.

He insists it didn’t. But gradually, after Maryanne died, he started contemplating finding out more about Carlo and his own lineage.

In the final years of his mother’s life, when Anthony had married his long-time partner, Carmel Tebbutt, and they had had a son of their own, his perception of family changed.

He became more curious about the other half of his heritage.

Then one day in the Catholic section of Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery, he was confronted by a question he couldn’t answer.

He would go regularly to Rookwood – at least once every calendar month – to make sure Maryanne’s grave was appropriately clean and tidy. She had paid $150 to reserve the plot 31 years before she died (and kept the receipt).

Visiting the cemetery, Anthony would sometimes take fresh flowers. Now and then, his young son, Nathan, would go with him.

The visits were – are – important to him, as much in honour of his mother’s character as her memory. Maryanne had always kept an immaculate home, regularly sprucing it with fresh paint or new tiles, despite periods when neither her bank balance nor her body were really up to renovating. She loved plants and especially flowers.

In his youth, Anthony would tell would-be visitors faced with navigating the block of identical two-storey houses on Pyrmont Bridge Road that his was the one with flowers – often red geraniums – in the window box.

On this particular trip to Rookwood, the still-very-little boy Nathan asked his dad a direct question. Where was his father?

‘It was just us,’ Anthony recalls. ‘And him asking where my father was – I remember that being an “oh dear” [moment].

What do I say to him?’

He fobbed off the question. It wasn’t too difficult.

‘You don’t have to respond to a three or four-year-old. You know? “Oh, look at the tree over there.” ’

The moment faded. But the question didn’t.

Anthony decided he needed to know something about the man whose Italian name they had both inherited – and whatever else he could find out about how they came to have it.

With his mother gone, the reluctance he’d felt about looking for his father started to subside because, as he says, ‘Then it wasn’t a matter of creating a difficulty for her.’

But the business of life in the present had a way of pushing aside the past. By the time he was thinking seriously about a search, he had been almost a decade in Parliament as the

Member for Grayndler, the whole time in Opposition.

With the Howard Government beginning to fade and the prospect of taking office in Canberra becoming a genuine one, Anthony Albanese, Manager of Opposition Business in the House of Representatives, channelled most of his energy into reaching the leather benches on the other side.

Now and then he would devote time to thinking about Carlo and whether he might still be alive. He confided in a few friends and colleagues and made some preliminary inquiries.

But he didn’t manage to join up the dots.

For a good while, politics overpowered the search. His party won office in 2007 and Anthony was preoccupied by the challenges of ministerial life and ensuring the smooth running of the Government’s legislative agenda in the ruling parliamentary chamber.

It didn’t leave a lot of time for genealogical musing.

Early that year, while they were still in Opposition, he asked his NSW Labor colleague and confidant Senator John Faulkner to help. John quietly lodged a request with the National Archives on Anthony’s behalf, looking for records of Maryanne’s voyage and the steward she met on-board.

‘Records held by the National Archives provide little information about this person, apart from the fact that he visited Australia as a crew member of the Fairsky,’ the archives’ Director of Access and Information Services, Anne McLean, wrote in response to Senator Faulkner.

She had asked around, trying to help further, and suggested some other avenues of inquiry in Australia and overseas, including archives in Britain and Italy.

The research eventually turned up a 1962 crew list for the Fairsky that included Carlo’s name and position as ‘assistant steward’, aged 30 – five years older than Maryanne. But beyond confirming he’d had a home port of Naples, there was little in the way of traceable information to go on.

Anthony mined the memories of his relatives, hoping for something to connect all the pieces. While his mother had been a great keeper of sentimental things, there was no correspondence from Carlo nor anything at all which might point to where he was.

Anthony found one black-and-white photograph of a smiling group of young people, dressed up and seated around a table in a ship’s dining room.

His Uncle George, known as Johnny, was there with his mate Mel Young, and a young woman, Joan Watkins, who would later marry Johnny and become Anthony’s aunt. The voyage produced more than one shipboard romance.

His mother was there in the photo too and standing opposite her, behind Joan, was a steward in a gleaming white jacket.

It had to be Carlo.

With both his mother and her older brother no longer living, Anthony asked Joan for all she could remember about the photograph.

She confirmed the smiling steward’s identity and did her best with recollections but she had no idea what had become of Carlo. It was all such a long time ago. As far as she knew, as far as any of them knew for sure, after Maryanne came home, the pair had never seen each other again.

Anthony ploughed on, enlisting the help of those trusted few friends and acquaintances, hoping to turn up something more contemporary.

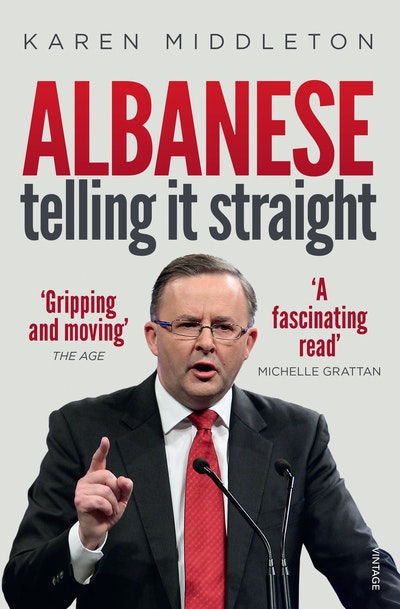

Albanese Karen Middleton

An updated edition of the personal story behind the very public political face of Labor’s Anthony Albanese.

Buy now