- Published: 5 November 2024

- ISBN: 9781776951161

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $40.00

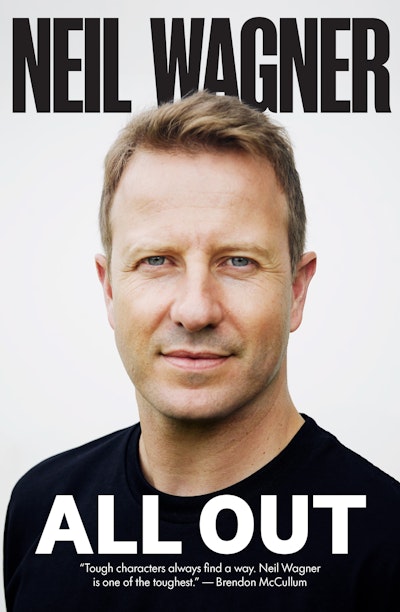

All Out

Extract

PRELUDE:

A WINDOW

I just want to fall.

If I close my eyes, I can still experience it through the mind of the 26-year-old I was on my third tour with the Black Caps, when I felt hopelessly lost off the field and was not yet wanted on it.

I was in the hallway of the team hotel, standing in the cool bite of air-con, the windows on one side looking over the swimming pool. On the other side, the hotel car park shimmered through the muggy heat of a Colombo day. It was some time in November 2012, in the days leading up to what would be Ross Taylor’s final test match as captain. A couple of months earlier, I had achieved my childhood dream of playing test cricket. But the elation of that moment was forgotten in the agony of this one, the lowest of my life. One of the windows was open and all that went through my mind was what it might feel like to lean forward and fall through it, to tumble into the blackness and be done with all of this. I felt useless. I felt worthless and insecure, trying so hard to be someone I wasn’t — and feeling like I was failing at that, too.

I just want to fall.

In that moment, I was almost exactly where I hoped to be when I had made the journey to freezing Dunedin from sun-drenched Pretoria just over four years before. I had finally qualified to represent New Zealand, and I already had a couple of test matches behind me. Sure, I hadn’t exactly set the world on fire in those two games against the West Indies, only taking four wickets at an average of over 50, but I’d given everything I had on a couple of lifeless pitches. I’d fought hard with the bat, too, twice coming in as a nightwatchman and both times surviving through to stumps. We lost the series two–nil, but I’d shown enough to keep my place in the squad for the next two tours — India and now Sri Lanka — even if I hadn’t done much but train and run drinks throughout the subcontinent.

In my years in Dunedin, playing cricket for Otago as I worked through the qualification period, I had a great bunch of mates who appreciated the heart and hard work I put into trying to win games for the team. I did it in my own way, with the bravado and aggression I had learned to play with growing up in South Africa, picking verbal battles with batsmen to get me into the fight and also to help chase my insecurities out of my mind. I felt valued in the Otago setup.

But that had taken time. I grew up speaking Afrikaans. English never came naturally. Many times I found myself walking away from conversations thinking, Hang on, they haven’t understood me here. I’d get frustrated with myself and the limits of my English. Why can’t you see it like I see it? That’s not what I mean. But time and familiarity with the guys made these misunderstandings far less frequent. The gap between what I meant and what others thought I meant shrank. In the Black Caps environment, sharing a changing shed with people I had played against domestically, some of whom had taken issue with the way I played the game, I had to start over. I felt totally alone, and that loneliness was devastating.

I was also young and arrogant. The South African cricket culture I came from was so cut-throat and competitive that I had always distrusted the advice of others, thinking they might have ulterior motives. I took that lesson of distrust with me to New Zealand. I desperately wanted to fit in, to show the guys that I was a normal bloke who just wanted to be mates, have a good time and play some cricket. But I didn’t know how to let down the barriers of my upbringing.

Craig Cumming, my captain at Otago, had become something like an older brother, but I didn’t want to call him up out of the blue from Sri Lanka and burden him with my shit. I didn’t want to confide in Mike Hesson, the recently appointed Black Caps coach who I knew well from his years of coaching Otago, or Ross, either. They might send me home, or they might think I didn’t have the mental strength to perform at this level. My international career would be over almost before it had begun. I’d worked so hard to get here. I wanted to prove my strength, not show my weaknesses. I was also feeling increasingly isolated from my family in South Africa, through no fault of theirs. This didn’t feel like the time to try to reach out — I didn’t want them to worry.

And things weren’t exactly rosy in the Black Caps changing shed. Ross would soon be replaced as captain by Brendon McCullum, and the team was swirling with speculation and rumour. I was so new to the environment that I knew almost nothing of what was going on, other than how it felt to walk into a hotel bar and witness a bunch of teammates who’d been excitedly chatting go silent when you came near. I was in such a deep hole, my thinking so scattered and my depression so self-centred, that all I could think was, Shit, were they just talking about me? It became easier just to order room service and eat alone in front of the TV than it was to risk rejection.

All of this swirled through my mind as I contemplated that window. I should’ve been happy, but inside I was miserable, feeling like a failure who was letting down the people who had made so many sacrifices to help an Afrikaans boy from the working-class suburbs of Pretoria chase his dream of playing cricket at the highest level. Maybe it was all a huge mistake. Even my faith in God seemed to desert me — and anyway, what kind of God would leave His son feeling this broken?

I looked at the window again.

I just want to fall.

My head was spinning. But then I started visualising the headlines: Test match cancelled because New Zealand squad member dies in a Sri Lankan hotel. What about my teammates? What would it be like for them, filing into their seats on the plane for the long flight home, my horrible death gnawing at their minds? I hate to let people down. It’s not always the healthiest instinct, but maybe here it saved my life, overriding that awful weight of negative emotion in my mind.

I can’t do this.

I escaped back to my room — shaking, jittery — and stepped into the shower. Everything felt wrong as I stood there with the water washing over me. A hot shower wasn’t what I needed so I tried a cold one. Not right either. I fidgeted with the temperature, but I couldn’t get comfortable. I got out, dried myself and went to the bed, staring at the ceiling, flat on my back, trying desperately to empty my racing mind.

I’m not sure quite how much time passed before I looked over at my phone. There was a message waiting from my friend Lana. We had met years ago, in Pretoria, and had sporadically kept in touch over the years — but more so recently after, unable to sleep one night, I had seen her online and sent her a message. We got chatting — just general stuff to start with — but the conversation had quickly deepened and soon I was confiding in her how low I had been, and telling her I felt I had nobody to talk to. And she said, ‘Well, you can always talk to me.’ She had quickly become my biggest means of support.

And now, when I needed a friend more than ever before, here she was. As I saw her name on my screen, I realised how close I had come to losing everything that I had worked so, so hard to build. I felt warm relief flood through my body as I typed my reply.

All Out Neil Wagner

An inspiring and revealing memoir about the relentless pursuit of dreams, and the highs and lows along the way, from one of the Black Caps' finest test cricketers.

Buy now