- Published: 29 August 2016

- ISBN: 9781760142414

- Imprint: Penguin eBooks

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 320

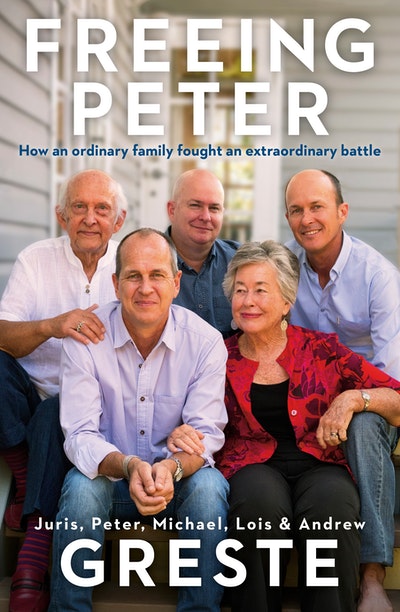

Freeing Peter

Extract

JURIS The importance of a big family Christmas was something I gained from Lois, but by 2013 it was a long time since we’d had one. Peter had been working as a journalist, mostly outside Australia, for more than twenty-five years, and Mike and Andrew had their own family commitments in other parts of the country. Lois had a much more settled family life growing up than I did. I was born in Latvia and came to Australia as a refugee at the age of thirteen after the Second World War, with my mother and two younger siblings. We did the best we could, but it was with Lois’s family that I first experienced Christmas Day as a family festival, and it became all the more precious as we raised our three sons.

JURIS I met Lois in 1960. Peter was born in 1965, Andrew in 1968, and Mike in 1971. We always tried to instil some Latvian tradition in our celebrations. The literal translation of Christmas in Latvian carries two meanings: ‘winterfest’ and ‘the turning of the sun’, or the winter solstice. The Anglo-Saxon concept is mainly about the birth of Christ, whereas Latvia balances that with the old pagan tradition. We would light candles on a real tree on Christmas Eve, and have port and Christmas cake. When our kids were growing up, that night was the start of the excitement.

LOIS A family Christmas became harder as the boys grew up and moved away to follow their careers. Andrew is a farmer near Wee Waa, seven hours’ drive from Brisbane, and Mike is a forensics officer with Queensland police in Toowoomba. But we still tried to organise special meals, play games and enjoy a relaxed time with whatever family members we could gather. In 2013 we celebrated with Mike and his family at their home. He put the stockings out for his two young daughters on Christmas Eve, and his wife Nikki brought in some of her Scottish family traditions. It was a fabulous Christmas, lovely and stress-free – all the more so, looking back.

Andrew and his wife, Kylie, and their three children were spending Christmas in Port Macquarie with Kylie’s extended family. Peter was the furthest away, of course. Since leaving Australia as a young man, he has only been able to come home for one or two Christmases. He’s been in Afghanistan, Iraq, Kenya, South America, lots of different places, often covering for colleagues who went home for the holiday.

In 2013 he was working for Al Jazeera English and living in Nairobi, Kenya. Over Christmas, he went to Egypt as a temporary replacement, but we still managed to talk to him, as we always did, speaking on Skype on Christmas Eve and again on Christmas Day. He told us that for journalists, the atmosphere on the streets of Cairo was hostile; some Egyptians regarded them as spies. I was anxious, and I remember telling him, ‘Be careful – if you go out of the hotel you might be nabbed.’

MIKE Peter moved around so often that for much of his career Andrew and I didn’t know where he was in the world. He’d spent many years as a foreign correspondent in conflict zones, and I always had mixed feelings about his safety. We were aware that he knew how to look after himself, but at the same time we were half waiting for the day we received a phone call with bad news.

ANDREW That November, I’d had a Skype conversation with Peter, catching up, seeing how he was doing. He said, ‘I’m going to Cairo in December.’ I said, ‘That’s funny, I’ve just seen a report about journalists getting arrested there.’ We had a joke about it. Peter said light-heartedly, ‘Oh, that was probably the Al Jazeera Mubasher journalists.’

Al Jazeera Mubasher were the locally based Arab journalists. Al Jazeera English (AJE), who Peter worked for, was a different operation altogether. At that point, confusing the two was still funny.

LOIS I won’t forget where I was when I heard the news. After leaving Mike’s place in Toowoomba a couple of days after Christmas, Juris and I went to our hobby farm, south of Laidley in the Lockyer Valley, outside Brisbane. We’d recently moved into a townhouse in Brisbane, and wanted to get away for a few days and decompress.

The farm, a sixty-acre block, has been an important place for our family ever since we bought it in 1981. We went practically every weekend and school holidays for the first couple of years, firstly to build the house and construct yards and fences, and then to look after our small herd of Hereford cattle. Peter and Andrew were teenagers, and Mike a bit younger, when we set ourselves a target of twelve months to build a timber house on the block. We did all the work ourselves and called it The Shed, though to some it would be no more than a permanent bush camp. It was a big project, and the boys learnt the value of working together.

We always loved the outdoors. For several years we’d gone to a sheep property in Mudgee, hiring a farmhouse, helping the farmer move the sheep. We also had camping holidays, sometimes long trips, moving to a new site each day. Particularly if it was late at night, we’d play the game of how fast we could put up our tent, pump and make up our beds, and be in them. We all had to cooperate, take our share of the work. It was fun and we became very good at it. Looking back now, it seems to me that much of what we did built a sense of unity while still allowing the boys to keep their individuality, a sense of their importance as members of the family.

JURIS Back when the boys were very young, we lived in Sydney, where we had a small yacht, and this also set a pattern of working together. We spent many weekends cruising around Pittwater and the Hawkesbury River, and soon realised that you need to be tolerant and cooperative to sail a boat as a family.

For the whole of our life together, we only ever had the one bathroom and I’m sure that also taught us tolerance, patience, and consideration of one another. The large houses of today, with their multiple bedrooms and bathrooms, don’t assist in family togetherness. I remember Christian broadcasters years ago closing their programs with ‘Remember, the family that prays together stays together.’ In our experience it was ‘The family that bathes together stays together.’

In recent years, our visits to the farm had been tapering off. Bungaree, as it is called, is uncleared, lightly forested land at the foothills of the Mt Mistake range in the Laidley Valley. As important as it had been for us in the past, by 2013 Lois and I considered ourselves lucky if we got there for a weekend every few months. It was always a place of rest and recreation, even though I worked like buggery. It’s an intoxicating feeling just to be out there, and I like doing woodwork, building chunky slab tables.

The remarkable thing is, when my brother Ojars went back to Latvia to visit, he went to a property that had once belonged to the family, and the only building that remained on it was an old barn. Lo and behold, it was almost an exact replica of the barn we’d built at Bungaree, even to the pitch of the roof. I’d had no idea. It’s uncanny.

The tranquillity of the farm when we drove up after Christmas stays in my memory. There was a sense of otherworldliness once we crossed the creek and left the bitumen for gravel. Daylight had almost faded as we unloaded the car. After thirty-odd years of going there, we followed a well-drilled routine. We lit the outside fire, cooked the foil-wrapped vegetables and tossed a few sausages on the griller. The old hurricane lamps and a few candles cast their soft shadows as we sat down for dinner. After all the Christmas indulgence and social overload, this was a welcome respite.

LOIS Then we got the call on the mobile from Mike.

MIKE It’s a bit like a September 11 occasion: you’ll always remember where you were. I was working an evening shift down at Gatton police station, when Nikki phoned. Connie Agius from the ABC had sent her a Facebook message asking if we were aware of Peter’s arrest. That was the first we’d heard about it.

I was slightly shocked but not panicked. I thought that even if it was true, Peter might be questioned for a couple of days and then at worst kicked out of the country. I called Andrew to let him know and ask if we should bother Mum and Dad.

ANDREW I had just walked in the door back home in Wee Waa, after our trip to Port Macquarie, when Mike rang and asked if I’d heard that Peter had been arrested. I was flippant, saying, ‘That’d be right, he’s probably been tangled up in some demonstration.’ It seemed to me a professional hazard in the parts of the world Peter worked in and nothing to be too concerned about. Getting arrested wasn’t the worst thing that could happen to him.

My wife checked her Facebook page and saw that she’d also received a message from Connie Agius. Kylie wasn’t sure how to respond. I said, ‘Don’t worry about it, probably somebody fishing.’

MIKE We checked the internet, and there were a few news reports coming through about Al Jazeera English reporters being arrested in Egypt. Even once we’d confirmed that the arrests included Peter, I wasn’t too worried. Part of me thought it was bound to happen after so many years.

We were more concerned with what to do about Mum and Dad. After moving house, they needed time to relax. Andrew and I were protective of them, not wanting to stress them before we had to. We later worked out that AJE had been trying to contact them, but only had their Brisbane number.

ANDREW I was thinking that Peter had been in sticky spots before and would get out of this one. He’d been in all sorts of war zones, and as a seasoned reporter he knew what he was doing. I told Mike we should wait to tell Mum and Dad after they got back. But then I remembered Peter telling me it was a little difficult getting around Cairo as a journalist. I grew more concerned when I went online and learnt a bit more about contemporary Egyptian politics. I hadn’t been following that. I knew it was a turbulent country, especially since the 2011 revolution, but had never thought anything more of it. Mike and I had another talk and we decided he should call Mum and Dad.

MIKE To me, it was still a bit of a rumour. I didn’t know what to tell them, other than that we’d heard Peter had been arrested. I said it would blow over, and they should stay and have their time at the farm.

LOIS The news came like a bolt of lightning, sharp and fearsome. It’s no doubt what every mother of a foreign correspondent dreads. My head was a mass of scenarios, but Juris and I held onto the thought that it couldn’t be true as we packed up and headed back to Brisbane. Still, it was the only topic of conversation in the car going home.

JURIS Receiving that telephone call from Mike was like an explosion that you desperately want to pretend did not happen. It shattered the serene evening, as though timed to cause maximum disruption and impact.

LOIS It had to be a mistake, or a false alarm. As we drove home, Juris and I recalled an incident when Peter was in Botswana. He hadn’t been able to find his car registration papers, which he needed to get across a border, and he rang us because we’d used his car a couple of weeks before, while we were visiting him in South Africa. He thought we might know where the papers were. The next morning I got about four strange phone messages from Peter, with other voices in the background, which sounded like an emergency. I thought he was in trouble at the border, so I sent his messages to the BBC, who chased people down all over the world trying to find out where he was. We finally got in touch with him, to discover that he was watching a sunset in Botswana, drinking a glass of wine. He’d accidentally sat on his phone and had been talking to the person he was with at the time of his ‘emergency’ call.

Things seemed more alarming because of how far away he was. We arrived in Brisbane to find messages on the phone and we immediately returned a call from Heather Allan, Peter’s boss – AJE’s head of news gathering. She confirmed that he’d been arrested, although at that stage they were still trying to find out what had happened and why he was in detention. AJE undertook to devote their resources to helping us, and we believed their influence as a big media organisation would enable them to quickly sort things out. We were not yet aware of the lack of love between the Al Jazeera Media Network and the Egyptian government.

Freeing Peter Andrew Greste, Juris Greste, Lois Greste, Michael Greste, Peter Greste

Freeing Peter tells the extraordinary true story of how an ordinary Australian family took on the Egyptian government to get Peter Greste out of prison.

Buy now