- Published: 2 August 2022

- ISBN: 9781761047183

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 240

- RRP: $38.00

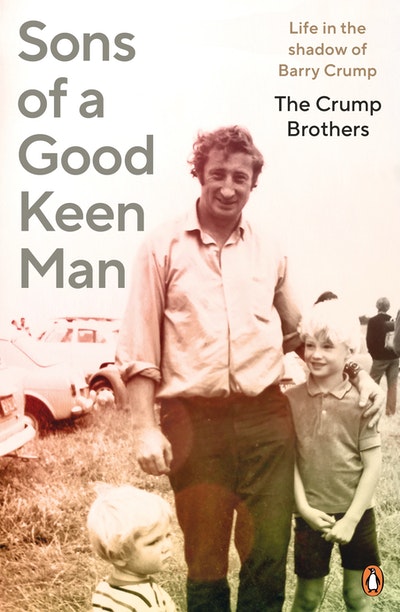

Sons of a Good Keen Man

Life in the shadow of Barry Crump

Extract

2.

Boys Will Be Boys

Our early years

MARTIN There is something that has always bothered me, and this may well be the perfect place to put it right.

The number of Barry’s children has been widely and incorrectly reported. Barry even got it wrong in his own autobiography! There, he says he has nine sons. He’s included some of his stepsons, which is nice but not accurate and confuses everyone. So here it is once and for all. In his life, Barry fathered six children, all boys: Ivan, Martin, Stephen, Harry, Erik and Lyall. There, I feel better already.

Barry lived with and played a part in a number of other children’s lives, but not his own. That was a responsibility he could not handle.

This was made clear to me only after his death, when his own horrendous and disturbing upbringing was revealed.

Barry and my mum would have eight marriages between them, which could appear messy to some, but for my brother Ivan and me, it was normal.

Mum had already lived a life before Barry came onto the scene. She was barely sixteen when she innocently and naively met and married a monster who was twenty years her senior. They would have two children together.

When the monster left Mum, he went on to marry Mum’s sister, and they had seven children together. So now my cousins were brothers and sisters to my brother and sister. I wish you well figuring that lot out.

It’s a shame my grandparents couldn’t have protected Mum from that monster, but they did provide a home for her in AstleyAvenue, New Lynn, in West Auckland, which they bought offthe poet Rex Fairburn in the mid-1950s.

The house would go on to become a wonderful family home for generations, and is where my own children were born. My grandmother Ruby, all five feet of her, was a dynamo, a great provider and tireless worker. She bought the house at Astley Avenue; she also died in that house, in 1980, after a full and colourful life. We wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

Ruby’s friends, who visited often, included the broadcaster Peter Sinclair. It was our large cane chair from home that he sat in when he hosted the very popular TV shows C’mon and Happen Inn on Saturday nights in the late 1960s.

She was also a good friend to writer Frank Sargeson, who incidentally wrote a short story about my grandfather Bill, titled ‘The Hole that Jack Dug’, because Bill was in the habit of digging holes all over the property – he just loved digging.

One day he dug a hole in the backyard so deep he couldn’t get out of it. Mum heard him from the kitchen calling for her to help him get out.

My brothers and I once built a hut, a decent-sized one at that, then one day after school the hut was gone. Bill had dug a hole and buried it, but what was hard to believe is that he didn’t pull it apart first – just buried it whole!

He was part Estonian – his father Martin had been in the Russian Tsar’s navy. He jumped ship and made his way to New Zealand. Our house became the Communist Party headquarters for Auckland.

Mum had a job handing out theatre programmes at the Saint James, to help out with money at home. Her circle of friends included all sorts of characters: university, literary and artistic people who would come and go from Astley Avenue. Mum’s parties were wild and alive with conversation, with an open door policy. We once had someone come to stay for the night and end up staying a year.

It was in 1957 when Mum, with a few friends, happened to visit the Vic pub in Auckland, where she saw twenty-two year-old Barry for the very first time. He was reciting the eye-watering poem ‘The Ballad of Eskimo Nell’. It was a long and bawdy tale that Barry had become very proficient at telling. All who listened were amazed how well he remembered every word, and how well he told it; they loved it. Even though it was full of foul language, it never seemed to offend anybody. Mum was intrigued.

Barry was fresh out of the bush, where for several years he had been in very remote areas of the New Zealand wilderness, hunting wild pigs and deer for the government. His meeting with Mum that Saturday night was to change his direction in life forever. Mum’s friends soon became Barry’s. He drank in the whole bohemian scene, along with a whole lot of whisky. He found it exciting.

It seemed the right thing to do, so Mum and Barry got married –both at just twenty-three years of age. The pair of them looked a little stunned on their wedding day at Astley Avenue.

Barry worked at a number of jobs and schemes – labouring, tree felling, driving trucks and trapping possums, to name just a few.

Mum became pregnant with Ivan. Barry wasn’t so sure about city life; he wasn’t so sure about married life either. They tried going bush together, where Barry was at his best.

Barry was so natural and at ease there – he could turn a piece of corrugated iron into a fireplace, a peach tin into a candle holder. A billy boiling over an open fire, and a yarn from the great storyteller himself. Mum often said you could heat your hands on Barry’s warmth. He was like the salt in the stew – you need it.

When he drew you in with his charm and storytelling, when he had you at your most vulnerable, this is when he could be his most cruel, which Mum ultimately found out.

They barely hung in there together, Mum and Barry, between the break-ups and the make-ups. They fought a lot, and they could get physical. Mum wasn’t shy about bashing Barry back either. She was tough.

In one particular fight, Barry threw a doughnut at Mum. It missed her and hit the wallpaper. The greasy shape of the doughnut would stay on the wall for the next twenty years, as the stain kept coming through each new layer of wallpaper that went up. We thought it was funny growing up and would tell our friends about it.

On another occasion they had decided to get back together, Barry came home for the big make-up and Mum had baked him a beautiful cake with ‘I LOATHE YOU’ iced on the top. He was furious. Apparently Mum wasn’t quite over his cheating.

And she was now pregnant with me.

Barry was rarely at home, and a short few weeks before I was born, he left and would never return to the marriage. Apparently, Barry turned up at Saint Helens Hospital when I arrived but Mum told him to get back on his horse and piss off.

They did try one more time to make it work – or Mum did. They decided to meet at a friend’s place in the Waitākeres. Mum had Ivan and I all dressed up, looking cute in the backseat of the car with a load of groceries that she had just bought. Surely he couldn’t say no to this.

He didn’t even turn up.

He’d been and gone and left a coat with £5 attached and a note: ‘Sell the coat. I can’t do this.’

They would both go on to marry others and have more children, but throughout their lives neither of them ever managed to completely let go of each other.

IVAN I was born in April 1958. According to Mum, I was a disturbed baby. Out of her five boys, I was the hardest to bring up. I was a disturbed child, as the psychiatrist once stated at school. Then I was a disturbed adolescent, and afterwards I became a disturbed adult.

I can’t blame anyone else for that. Just my good luck.

It’s manifested in many ways. I once looked up the qualities of a sociopath and was surprised at the similarities to my personality. I don’t think there’s anything external that caused it, though exasperation may have pushed me a bit that way.

I spent a fair bit of my life doing destructive things. I enjoyed being a vandal. It gave me great glee to fuck things up, and I had no discipline or guidance. I was allowed to behave badly, so I did.

There are many possible ways to describe my terrible behaviour. But the end result is that I was a massive cunt to the ones who relied on me.

It’s not that I didn’t want to be normal – I just couldn’t do it. My brother Marty has been the opposite – a good dad, provider, and the rest. He’s looked after me, alongside our truly awesome mother. Without her, I wouldn’t have made it.

For a few years, more than once, I considered suicide.

ERIK I was born in 1965. Six weeks later, Mum took me to Holland to live with my grandmother, where we stayed for the next several years. I grew up speaking Dutch and enjoying treats like drop and speculaas. It wasn’t until I was almost five that we returned to New Zealand, taking the long way by boat.

In Holland, Mum had told everyone that her husband was working back in New Zealand and was hoping to join us soon, but that was only so she wouldn’t be shunned as a fallen woman in a land that was still very conservative.

In reality, they’d never been married. I was conceived in the back of a Volkswagen one night after a party, and Barry scarpered soon after he discovered Mum was pregnant.

Mum’s a photographer, and I would often come along as she travelled the country in her Beetle, exploring and taking pictures. On one of these trips, she took me to meet Barry. Years later, she gave me a photo of the two of us, a small boy standing proudly beside a tall, smiling man, but I can’t remember that day. It was the only time I ever met him.

In those early years, it was just me and Mum, and I was free to roam and play as I wanted. I revelled in the freedom.

A few years later, she met another man and I gained a stepfather. At first, I gravitated towards this new man, who filled a Barry-shaped hole in my life. At one point, I even asked to take on his surname. But then my sister came along, and then my younger brother, and things changed. I found myself on the cutting edge of his vicious moods.

He would take off his belt and whack me for being too noisy, while his own children, playing alongside, were little angels who could do no wrong.

One Christmas, I was excited when he gave me a huge parcel. I tore off layer after layer of wrapping paper, only to find a scrubbing brush.

‘You can use it to clean my car,’ he said with a smirk.

Some years later, he threw all my clothes out of the second-storey window onto the driveway because he was sick of having me around.

He wore me down. A rough shell began to form around my heart to keep the pain at bay. Alone in my room, I would seethe with anger and despair, and even fantasised about killing him, so that I could be free.

Then finally, when I was in my early teens, we shifted to another house – just me, Mum, my sister and my brother.

At last. I could breathe again and slowly, gradually, I began to heal.

MARTIN We didn’t have a lot growing up at Astley Avenue, but we were happy.

Mum’s parties were something not to be missed. When I was just five years old, I should’ve been in bed, but I wasn’t going to miss out on any of the fun. Besides, there was always a bowl of those little red polony sausages with tomato sauce, and I was having me some.

I can still clearly remember a particular night when our house was heaving with people, music, smoke, talking and laughter. I was in my pyjamas about to sneak another sausage when I was handed one with just the right amount of tomato sauce on it by a very kind man. I instantly liked him, and not just because he was giving me what I wanted. There was something about him. I trusted him.

He got me several sausages that night. Later that evening, I was sitting as happy as you like on his knee. It felt right, it was right.

Some weeks later the man was at our house again. After he left, Mum announced to us all that she was going to marry him. And she did! Walter Lester – Wally – became my stepfather.

Certainly a day to celebrate. We all struck the jackpot to have such a decent, kind and wonderful man come and live with us. Mum chose well this time. And he wasn’t just taking on Mum, but also Mum’s two children born to the monster, and two more children to the famous Barry Crump.

The monster at this time was still coming to our house, bullying and menacing Mum.

On one occasion, the monster brought his brother. Wally took them both on, and it gave him a fight to remember. They smashed a heavy, jagged glass bowl on Wally’s head, fracturing his skull. He was sitting in our wash house out the back with his hands on his head, blood dripping from in between his fingers. I asked Wally if he was all right. Without looking up, he told me it was just red ink and I was not to worry.

He was protecting me. He was protecting us. Although I was very young, I can still remember the gravity of the situation.

I was standing in the driveway with Mum when the police arrived to take the monster and his brother away.

The monster never returned to Astley Avenue.

I must thank Wally for the wonderful life he gave us; he worked so hard and provided for us all – took Mum on trips overseas, taught me how to cook, made us feel safe.

Wally and Mum would have two sons of their own: my younger brothers Guy and Morgan.

LYALL Mum was pregnant when she met Barry at the pub in Auckland on that sunny afternoon.

‘What’s your problem?’ he asked, taking in her beauty before staring at her swollen belly.

Love might not have been instant but the spark was born and by the next day they couldn’t rid each other from their thoughts.

I don’t remember Barry smashing Mum in the face and putting her in hospital. I didn’t know about the violence he’d been through, nor did I know about Mum’s pain of losing her mum and living in hardship and poverty.

This was in Waihī, where I lived with my brother Al, my mother and Barry, where the sun beamed on fresh grass and golden sands.

I hardly remember us sailing to Europe, going through the Suez Canal. There are only vague memories of the dope fields of Morocco.

I’m told Barry thought it funny to make me smoke hash. I was two years old and, understandably enough, Mum was horrified.

We once had dope drying on the bonnet of the Land Rover and the police pulled up behind us. Barry slammed on thebrakes, sending the dope flying forward before coasting the car over the top of it and casually rolling open the window.

‘Yeah, g’day mate . . .’

There are just-as-vague memories of me drinking beer, wearing lederhosen, drunkenly singing, at a pub in Germany in 1972. Then crying, being comforted by Dad, Mum and my brother, being smothered in love.

And then travelling again, through narrow country roads, alongside open fields, people shouting and crying, and, all of sudden, no Dad.

MARTIN I know now that Barry visited us on occasions, but I don’t remember meeting my father until I was nine.

Mum had always tried to protect us from Barry, from his charm, from the promises he’d never keep, and from the hurt that would inevitably come.

It was May 1968. Barry was on the phone with Mum, and he asked her what I was up to. She told him I was interested in carpentry and doing well.

‘Put Martin on the phone,’ he said.

Mum handed me the phone and said, ‘It’s your father.’

I instantly felt nervous.

‘G’day mate. Our birthdays are pretty close together – I reckon we should go out and celebrate. What do you think?’ Barry’s birthday was on 15 May; mine is the 29th.

I went from nervous to impossibly excited. I said that I’d like that very much.

‘I’ll pick you up at six o’clock. We’re going out for dinner and whatever else we feel like.’

I was excited for the rest of the day.

Six o’clock came and went, excitement now gone.

I was sound asleep when he turned up at 11pm. I woke up as he sat on the edge of my bed. He handed me two cold cheeseburgers and a hammer, then disappeared into the night.

I was sitting in the lounge at Astley Avenue when I next saw Barry, a few months later. He came in the front door and Ivan, who was just ten years old, started following Barry like a puppy – from the front door, past the lounge and kitchen. Ivan was bouncing around him, wanting his father’s attention. They didn’t see me watching.

Barry was in no mood for this as he made his way down the hallway, out to the backyard to where Mum was hanging clothes on the line. From the end of the hallway, I heard whack! Then I saw Ivan walking back into the kitchen with a look of such utter rejection and hurt.

Barry may as well have bashed me as well. I felt my brother’spain and I hated my father for it.

This is when I started to see what Mum had been protecting us from.

LYALL I carry memories from Hurst Green, Sussex and London, the seaside, kind people – Mum and Al, no Dad. I helped Mum pick strawberries; we were listening to the Beatles sing ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, and I felt Mum’s struggle and the bottomless love she had to give.

I must have been three when Mum took me up the lane and across the busy road to the kindergarten. I learned to talk and be with the other kids. Al only went there for a little while. I think he ended up going to the bigger kids’ school, where he made friends with the mean boys. I guess that was when I realised we were somehow different to each other.

Mum made friends with a man who gave us presents.

I painted myself with the hash oil he’d left out when he and Mum went for a walk. When they got back, he was so angry he thrashed me with his belt. I cried and missed Dad as Mum cleaned me up. Al had told me not to play with that stuff.

All of a sudden, we were back in Morocco – the police again.

Not fun this time: jail for having seven kilos of high-grade hashish lashed under the car.

I had my fourth birthday in that jail. The moustached guard gave me a matchbox.

The guy Mum had met took the rap – we were out, and Barry came to get us. I was so happy to see him, smell him and hold him. We were going home, but I didn’t remember where that was.

The first sign I was disturbed was when I made a house from envelopes under my bed, then lit it on fire. I didn’t utter a word of warning to anyone – just carried on as normal, playing with my brother in the lounge.

If my new dad hadn’t moved so quickly, it would have burned the house down and possibly even killed us all.

I didn’t know or care about his history. All I knew was that he was my new dad, a different shape from the last one but somehow the same, even better.

It was 1975 and we were back in New Zealand when I first met him, at the age of five: a solid bloke, a builder, surfer, world traveller – and my new dad. I loved him straight away.

He took us on adventures, camping at his favourite surfspots, tenting around a fire, swimming in the ocean, riding the waves on our foam boards, making new friends at every small town. It was a different life to the one I’d imagined with Barry.

My new dad showed surf films and made ads for television. I got the idea that I might be an advertising guy, write the ads or something – make him proud of me.

Our new dad took Al and me to Huntly and we carefully dismantled an old farmhouse. Al and I loved it, getting grubby and bonding with our new dad.

He took me to Hamilton on my own once, to see a surf movie called The Endless Summer.

I was lost between two worlds: one steady with Mum, my new dad and Al; the other with Barry and his mysterious world of writing and hunting, being at the pub, smoking rollies, drinking beer and whisky, telling tall yarns, being a central and iconic character.

I think we enjoyed living in Herne Bay in Auckland, me and my new family. We made friends and explored and I got in the habit of finding things – money, jewellery. I’d pick up anything that looked useful or interesting. We were losing our British accents and settling in to being Kiwi.

We could feel the loving anticipation, the winds of change. This time, though, we were wary, experienced, tainted.

I could say that it was Barry’s father’s fault for being so tough on him. And his father could say that he was who he was because his father was affected by his involvement in the war.

Now I was lighting a house of envelopes under my bed and I didn’t know why.

‘Could you make us a sandwich?’ Al asked our new dad when we first met him. He smiled kindly. He was great.

‘Sure, what do you want on it?’

‘Jam,’ I said eagerly. Then I hugged him. He pulled away. His smile faded and he hurried off to make our sandwiches.

I told him about the time a rat had taken a jam sandwich from my hand when we were living in England. Al told him about the bird-eating spider we saw living in the high corner of a toilet block in Morocco.

He took us on an adventure through the bush on a long, winding, narrow and dusty road out to the west coast – Piha. This was the place, he said. It’s where the dream began. A new beginning where they could let their love grow and flow.

He was amazing, my new dad.

He built us a cool house. His friends were nice and they made friends with Mum.

She started a business in the rag trade downstairs. Our rooms were next to it, by the old wringer washing machine.

Mum learned to surf and taught us. We lived halfway up the hill, just down from Pendrell Road, below the top rock – an old magma chamber from one of the many extinct volcanos that circle and look down at the beaches and relentless waves of the Pacific Ocean.

The bus ride to Oratia School was a long, loud, bumpy journey.

Al remembered that Barry’s brother lived close to the school.

‘What are you buggers doing here? Why don’t you stuff off –you don’t belong around here!’

‘Come on, Lyall. He doesn’t love us.’

We knew in our hearts that Barry and his family were not ours. Our family was out at Piha.

I was eleven and into drumming. Dad bought me a small kit. Iended up having to move it to the neighbour’s place – a full-blown alcoholic, complete with crazy mates and a piano. The man was a musical genius and taught me all sorts of beats. He taught me a lot of things actually, and so did his wild and drunken friends.

I learnt a bit about the blues, classical and operatic music.

He also taught me a bit about crazy – how to go there but also how to come back. It was a scary sort of place: windows closed, curtains drawn, citrus rotting, bread baking, clutter and full ashtrays. He would often send me on the dreaded long walk down to the shop to buy him and his pal cigs.

IVAN Barry was an awesome dad to many children, just not his own. Apart from the fact that he always shot through, no matter who from, his own kids were just too much for him. Having said that, he did once come to the family home to get me and take me with him. My mother seriously threatened to put an axe in his head. He got the message loud and clear