- Published: 30 July 2018

- ISBN: 9780143771296

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $40.00

Steven Adams: My Life, My Fight

Extract

At the end of 2010 I went along to a Junior Tall Blacks training camp because Kenny was the coach and I was able to go without paying the fee. That’s right, in New Zealand promising young basketballers have to pay to trial for national teams. Kenny had invited the coach from the University of Pittsburgh, Jamie Dixon, to watch and scout for potential recruits for his NCAA Division 1 side. I performed well at the camp and Jamie was interested right off the bat. We had a talk and arranged for him to come and see me train a bit more in 2011. But he made it clear on that first visit that he wanted me to go to Pitt on a scholarship.

I never ended up playing for Kenny’s Junior Tall Blacks team. I was obviously good enough – a national MVP should be able to make the junior national team – but I couldn’t afford it. To represent New Zealand as a young athlete costs a lot of money, not just in basketball but in all sports. Being selected for an age-group national side to play in an international tournament would cost each player thousands of dollars. I knew of players who went on every trip, at least once a year, because their parents could easily afford to pay for each tournament. But there were a lot of players, most of them brown, some of them the best in the country, who never once represented New Zealand because they couldn’t afford to trial, let alone to fly overseas. I hate to think how many guys I played with who could have had careers in basketball if they’d just been given more help (like I was) when they were younger.

While I didn’t mind the hours of training and gym workouts, I was finding it harder and harder to be enthusiastic about schoolwork. I couldn’t figure out why I had to spend at least six hours a day doing things that wouldn’t matter if I succeeded in becoming a professional basketball player. I want everything I do to be in pursuit of a greater goal and, by the start of my final year at Scots, I wasn’t seeing how school was helping me reach my goal.

But while the end goal was never to get a scholarship, it was a required step in continuing to improve my game, and therefore schoolwork was a vital area that I was neglecting. That is until Blossom sat me down and gave it to me straight. Without good grades, I wouldn’t get a scholarship. Without a scholarship I wouldn’t get to America. And if I didn’t get to America, there wasn’t much chance of me getting to the NBA. That was all it took. Just a no-nonsense explanation of why I needed to succeed in school and my attitude changed completely.

We found out which requirements I’d need in order to study at a Division 1 college in America and realised that I was taking all the wrong subjects at school. In my first full year at Scots, I didn’t progress much in the classroom. Where I did progress was in catching up socially and integrating into the school community. So, to no one’s surprise, my grades weren’t very good that year. A lot of papers I didn’t achieve and the ones I did were the unit standards, which were usually easier to pass. In 2010 I was a Year 12 student and started to be more comfortable in the classroom, but I still struggled a lot, especially with written subjects like English. So I took all the classes that students take when they know they’re not good in the classroom, like physical education, computing and tech.

It soon became clear that I couldn’t keep taking the subjects I wanted and be accepted into a Division 1 college. For the first time in my life I started having regrets. Why hadn’t I worked harder when I first got to Scots? Why had I never gone to school in Rotorua? Why had I acted like school wasn’t as important as basketball?

The principal at Scots spoke to one of the English teachers, Ms Milne, and asked if she would tutor me to get my grades up. She said yes (I’m starting to wonder if anyone ever refused to help me) and would come to meet me every study period for an extra lesson.

It wasn’t easy. I might have never missed a training and always put in 100 per cent on the court, but the same could not be said for my work in the classroom. Ms Milne, Ms Parks and Ms Esterman, the librarian, were my three school mums and they had their work cut out for them. To get my literacy credits I had to complete a reading log, which meant I had to start reading.

Two years earlier I had met Ms Esterman in the library and she had asked me what books I liked to read. I said, ‘Where’s Wally?’ That’s where my interest in reading was at. She found a Where’s Wally? book from the primary school library and we went through it together before she gently suggested that I try out a short novel. From there it was very slow but steady progress until in 2011 she handed me Catch Me If You Can, a story of a con-artist, made famous by its movie version featuring Leonardo DiCaprio. I carried that book around with me everywhere. But I hardly read it. Ms Milne would make jokes about me always having that book in my hand; I had every intention of reading it, but most of the time I’d get through half a page then get distracted by something more interesting, for example, a tumbleweed blowing across the rugby field. Even the title Catch Me If You Can became a joke among the teachers, who had to chase me around the school trying to get me to complete their assignments. It wasn’t that I didn’t take schoolwork seriously, it was just so much harder for me to work with my brain than with my body.

I loved maths and classics. Maths, because everything is either right or wrong, and once I understood a formula I could sit all day solving problems and getting a kick out of each correct answer. Classics I loved because of the stories. The best mark I ever got in school (besides the PE physical that I aced) was a merit in a level 2 classics assignment. The learning material was pretty much the same as all the other assignments that year, but the difference was that we had to deliver our work as a seminar. I knew what story I wanted to teach the class about, so I went up in front of them and told it. I spoke for 15 minutes with no notes, no cue cards, nothing. My issue was never that I didn’t understand ideas and concepts, it was that I couldn’t write them down.

When the principal came into the common room the next week and announced that Steven Adams, the guy who could barely read when he started at Scots, had gotten a merit for his classics seminar, I’d never been more proud. All my mates were shocked, and I played it off as if I just got lucky, but in my mind I was strutting around like a peacock.

Ms Milne knew that I worked better verbally, so we went through most of our tutoring sessions having conversations about things I was reading, rather than her making me write down a bunch of answers. I requested a reader–writer for exams, someone who sits with you and writes out your words for you. Some people might consider having a reader–writer to be a bit embarrassing or something to be ashamed of, but I didn’t hesitate in asking. When there was a mix-up and one wasn’t there for an exam, I didn’t start until she arrived.

I am proud of my strengths, but I am also aware of my weaknesses. I wasn’t actually dumb – I understood the concepts and knew what to say – but barely going to school until I was 14 meant my writing was a hindrance in timed assessments. I think that if you have something you’re not confident with, own it and accept the extra assistance when it’s available. If I had refused to be humbled by all those who could help me, I’d still be sleeping on a mattress in Rotorua.

Ms Milne wasn’t just my tutor during her breaks and after school, she also played the role of part-time driver. If we had a lesson after school and I needed to get to the gym to meet Blossom, which was every day, I’d wait by Ms Milne’s car and ask if she would be going through town on her way home. She almost always was – or at least that’s what she said. She would drive me into town in her tiny RAV4 with no leg room and drop me off at the gym. I’ve never been one to let pride get in the way of a free ride.

To everyone’s surprise but my own, spending so much more time at school didn’t take anything away from my basketball. I was still training every morning with Kenny, although my new training buddy was a guard called Jah Wee, who had the biggest hops of anyone I’d met but wanted to work on his court reading. He played in the Wellington rep team and lived not far from Blossom and Kenny.

Kenny would be outside Jah Wee’s house at 5.20am each morning and if he wasn’t waiting outside, Kenny would drive away. For two years, Jah Wee was always waiting outside. Then they would come by Blossom’s house to pick me up and I would never be outside, so Jah Wee would have to come inside and get me. I can’t count the number of times I woke up to Jah Wee standing over me, telling me to hurry up.

As I started to get some media attention later that year, reporters loved to mention that I would have to be up and standing outside by 5.30am every morning. In reality I was given a lot of passes from Kenny, and Jah Wee was the only one who risked missing a training by sleeping in because no one was going to go inside to wake him up. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to train; I’ve just never been a morning person. One of the best things about playing basketball for a living now is that I never have to wake up at 5am. I start work at 9am like a normal person.

During one training, Kenny casually mentioned that he had been speaking to Pero Cameron, a former Tall Black and current coach of the Wellington Saints, the city’s team in the National Basketball League. Cameron apparently wanted me to play for his team in the 2011 season.

Some of us in the Wellington rep team had been training occasionally with the Saints, but I thought it was just to get in some extra hours in the gym, not to actually play for them. The training had been a massive step up and improved my game heaps in a short time as a result of matching up against much stronger and more experienced players. The Saints had guys like Nick Horvath and Kareem Johnson in their squad, who had both played basketball in America. Nick had won an NCAA Division 1 title playing for Duke University and he had also played for the Los Angeles Lakers and Minnesota Timberwolves in their Summer League teams. Guarding Nick and Kareem quickly made me realise that to play in the NBA you have to be at a whole other level of toughness because even in practice those guys would throw you all over the court.

My first game playing for the Saints was at TSB Arena in Wellington, our home court. I was so nervous before the game that I threw up. Heaps of my mates from Scots College were there as well as a whole bunch of teachers. I’d never had that many people come to a game just to see me play and that didn’t exactly help with my nerves.

I have never been as anxious about a game of basketball as I was for that first Saints game. Not even playing my first game in the NBA compares. I don’t remember who we played, but we won, and I didn’t make a fool of myself – and that was all that mattered to me. As the season went on, I started to come off the bench earlier and got more minutes, which grew my confidence and let me finish the season with some really strong games behind me. It was during this season that I finally grew confident enough to dunk on people, not just around them.

We won the championship that year, winning the final against, of all teams, Hawke’s Bay, and continuing my unbeaten streak with Wellington basketball teams. I was named Rookie of the Year. I got to line up against the best players in the country, and the Saints got a big man for free because if they had paid me I would no longer be an amateur and would have been ineligible to play college basketball in the United States. Kenny was really careful about that. He’d known some guys who didn’t understand the rules and had accepted payment for playing in a random tournament, and then lost their scholarships.

University of Pittsburgh had committed to giving me a full scholarship the following year and I certainly wasn’t about to put that in jeopardy. The Pittsburgh coach Jamie Dixon had visited New Zealand again after the Junior Tall Blacks camp and had come to a game that our Wellington rep team was playing against Kapiti to warm up for Nationals. Kapiti have never been a strong basketball unit so there wasn’t much to see, which is lucky because, thanks to the many weird NCAA recruiting rules, Jamie had to stand outside the whole game. If he’d come inside, though, he would have seen me shattering the Kapiti College backboard and breaking their hoop. I’m not sure if that would have helped or hurt my chances, now that I think about it. Either way, Coach Dixon soon confirmed my scholarship offer.

I never considered other colleges in America besides Pittsburgh because there weren’t any to consider. Back then, to get a scholarship you needed a connection to a college and the only one we had was Jamie, who had played basketball with Kenny decades earlier. These days, there are more and more college scouts coming to watch the New Zealand Secondary Schools National Championships every year, which is incredible to see because it gives players options to find a US college that best fits them as a player and as a student. I went to Pitt because they were the first to ask.

In August 2011, I attended the adidas Nations tournament in Los Angeles for the second time. I had gone the year before when it was held in Chicago and while I thought I did okay, I definitely didn’t blow anyone away. The best part of it was getting a whole bunch of free adidas gear. I could finally stop wearing the same three T-shirts everywhere and I didn’t have to buy any new socks for years. But in 2011 I had made huge improvements, I had upped my training to twice a day during the school term and four times a day in the holidays, and I was feeling fitter than ever after my season with the Saints. The tournament was a massive success. I played with Team Asia, and although we lost all our games we were at least competitive. I ended up averaging 22 points, 16 rebounds and two assists over four games. They were my impressive stats.

My unimpressive stats were the few media interviews I did. I can’t bear to watch any of those old interviews now because I sound completely lost. During one, the poor interviewer was getting absolutely nothing from me, like even shorter answers than Russell Westbrook gives these days. After a few minutes trying to get more than two-word answers, he asked, ‘What are your strengths and weaknesses?’ I looked at him for a while, thought about it, and managed to come up with ‘I dunno, just . . . running.’ I seriously listed running as a strength. Wanna know what my second strength was? Playing. I nearly cry thinking about how bad I was at answering questions back then. Like anything, it’s a skill and one I clearly hadn’t learned at that point. Thankfully, players aren’t recruited solely on how well they can string a sentence together or there would be a lot fewer players in the NBA right now.

I heard later that what impressed the coaches and reporters wasn’t that I was scoring lots of points, but that I was able to score points and defend well against the big names in my recruiting class, the biggest being Kaleb Tarczewski, another 7-foot centre. Kaleb’s name had been floating around the tournament as one to watch, but I knew if I just played my own game and hustled on defence, I wouldn’t have any trouble matching up against him. I came away with 20 points, 24 rebounds, and four assists. Kaleb had 10 points and four rebounds.

To be honest, I was used to this happening. Even in New Zealand I was often considered an underdog in match-ups with big guys whose names had been thrown around the circuit well before I’d even started playing. But I always managed to outplay them.

The first examples were two North Shore players, Isaac Fotu and Rob Loe. I like both those guys and they are great players, but the first time I played them at under 19s, everyone expected me to be outclassed by their experience. Instead I was able to outhustle and outmuscle both players on the way to another New Zealand national championship.

During my final year of school, I really started to get the media’s attention. Being 7 feet tall was enough to make it into the local newspaper every once in a while, but after I signed on to the Saints, I started to get some real coverage. And New Zealand quickly displayed its usual tall poppy syndrome. Yes, most of the attention was good and supportive, but there were still a lot of people saying that I only got picked because I was tall or – and this was a real weird one – because I was Valerie Adams’s brother. I knew how good I was so it didn’t bother me too much, but it’s hard to completely ignore comments like that, especially as a teenager.

As I started to play more for the Saints and to show my worth, the comments didn’t go away, they just morphed into new insults. Since they couldn’t say that I wasn’t good enough for the Saints, they started saying that the NBL itself wasn’t that great and once I got to America I’d soon learn that I didn’t have what it takes to play Division 1 ball. I don’t know what it is with some New Zealanders, but they really take the notion of being ‘humble’ seriously. So seriously that they’ll do their best to humble you if they think you’re not doing it for yourself. Did people want me to say that I didn’t think I could make the NBA or succeed in basketball? Did they want me to act surprised that recruiters were saying I was good? I didn’t train every morning for four years to not be good or to pretend that I just got lucky.

The other thing that I wasn’t prepared for were the assumptions about my family and my childhood. I’d deliberately been vague about my background because I preferred to keep some things private, and I didn’t want to suddenly have my family in the papers. Somehow, in doing that, I got an even worse outcome. One mention by me of not going to school and suddenly I was ‘living on the streets’. A random anecdote about being friends with someone whose dad was in the Mongrel Mob and soon I was reading about how I was on the verge of joining a gang. That one made me laugh because if I’d even tried to get in with a gang my sister Viv would have yanked me right back out again. Even though I thought these stretched truths were funny, I knew it was hurtful to my siblings who had looked out for me and were now being painted as absent or even neglectful guardians. No one ever mentioned my mum, even though she was around, which I’m sure she didn’t appreciate.

The family talked with Val about how we should deal with these stories as she was the only one with media experience, and she said the best thing was to say nothing. So that’s exactly what I did. I said nothing and watched as Steven Adams became an orphaned kid living on the streets, stealing and getting into fights, and about to join a gang before he was plucked from the gutter and brought to Wellington.

By the end of 2011 and my years at Scots College I had comfortably passed all the papers required for entry to college in the US. It meant I wouldn’t have to go to summer school at Pittsburgh or take a bridging academic course to qualify for my scholarship. Unfortunately, because so many players end up having to delay their college careers as their grades are unsatisfactory, Pitt had taken the safe route and enrolled me into Notre Dame Preparatory School in Massachusetts. Even though I didn’t need to go there, they kept me enrolled anyway so that I could get used to the American style of basketball. I figured that was probably a good idea, but it meant having to leave for the US almost as soon as the New Zealand school year finished instead of having a break to spend time with friends and family.

Once again, I shrugged it off knowing that if I let myself dwell on it for too long it would be no good for my game and my mental wellbeing. Besides, Notre Dame sounded like a cool place to learn the ropes of American basketball, and I couldn’t wait for the step up in intensity.

While I had been focusing on my basketball I still tried to play other sports as much as possible. Experts used to say that kids had to choose their one sport as early as they could and stick to it. But my time spent playing rugby and doing athletics was only ever beneficial to my basketball. So while I was training hard out with Kenny I was also learning how to throw the shot put.

Every year, schools around New Zealand have athletics days to pick a team to compete in local, then regional, then national meets. I won the shot-put event at Scots College because I was the tallest and no one else bothered with shot put. It’s simple maths; I had the better angles. Then I won the Wellington and the regional competitions and started to think maybe I was actually the man at shot put as well as basketball. It wasn’t a completely ridiculous idea, as I at least had the genes for it. By then, Val was an Olympic gold medallist, winning at Beijing in 2008, and she would go on to win gold at the 2012 Olympics in London too.

The Wellington throws master, Shaka Sola, who represented Samoa in discus and shot put, had seen me throw at the regional meet and told me I should head to the athletics stadium that weekend to have a session with him. I didn’t have any basketball on so I went along and soon figured out that he was the Kenny McFadden of throwing events. We went through some basic technical drills and I had improved my throw by the end of that first session. The thrill of such an immediate result got me hooked and I trained with Shaka every weekend for three months until the National Secondary Schools Athletics Championships.

I could see straight away why people get into individual sports like track and field. For someone who lives off seeing results, each increase to my PB was a new high. Basketball let me see improvements on the court as well, but with something like shot put, the evidence was right there in the measurements, and I became addicted to seeing that number go up.

Even though I’d only been training for a few months, my naturally competitive nature meant that I went into the national meet fully expecting to win. When I began training with Shaka, I was throwing around 11 or 12 metres. By the time Nationals came around, I was throwing 15 metres and feeling confident.

What I had failed to notice were the occasional news stories about a guy called Jacko Gill who had set a junior world record at the age of 14 and won gold at the World Junior Championships. I showed up at the meet and went through the warm-ups with all the other part-time throwers while Jacko sat stretching on the side. He didn’t look very big and was certainly not as tall as me. Then he got up for his one warm-up throw and heaved it close to 20 metres. ‘Man, what a dick,’ I thought. ‘At least pretend that you’re trying.’ I finished up in fourth place and decided to end my athletics career then and there. I knew if I kept training I could add a few more metres to my throw and maybe even get somewhere close to Jacko’s distances, but sometimes seeing someone excelling in their passion is enough to convince you to stick to yours.

At the end of my time at Scots College I was asked by the principal if I would be willing to make a speech to the entire school about what I hoped to be up to in years to come. Scholarships to American colleges were rare even then and I knew the school was proud of me for getting through my years at Scots and achieving academically. I hesitated for a couple of reasons, the main one being that I’d never spoken in front of a crowd before. I had gotten comfortable doing oral assignments in front of a class or a couple of teachers, but hundreds of students was a whole other deal.

I burst into Ms Parks’s office and told her I wasn’t doing it. She had no idea what I was talking about as I ranted about why I couldn’t possibly speak in front of the whole school and why everyone would think I was dumb. She didn’t say anything. She just looked at me and I knew I had to do it. People had started to follow my story by then and I’d noticed some of the younger kids at the school seemed to look up to me, in every sense. It was the least I could do for a school that had taken a chance on a scruffy kid and helped him reach his goals. I worked on that speech with Blossom, I worked on that speech with Ms Parks, I worked on that speech with my friends. I worked on that speech more than I had worked on any assignment or exam in all my time at school.

I included a little bit about my childhood – a topic I had staunchly avoided until then. I told them how I hated all of them when I first started at Scots and they laughed, maybe thinking I was joking. But I also spoke of how going to Scots had made me realise the importance of an education and that no matter what happened to my body, I’d always have the things I learned in the classroom. I spoke well. I was no Barack Obama, but I managed to get through it without any major fails and I got a huge round of applause. When I looked around at everyone I saw that a lot of the teachers were crying, particularly my three school mums. That’s when I knew I’d done a good job. You know you’ve done well on the basketball court if your team wins and you contribute. But you know you’ve done a good job in delivering a speech if you make people cry.

It took three and a half years at a very expensive private school for me to realise the importance of an education. When I walked into Scots College I hated everything about it and I only wanted to be playing basketball. When I walked out of Scots College for the last time as a student, I knew that playing basketball wouldn’t be possible without an education, and learning would still be there long after basketball was gone.

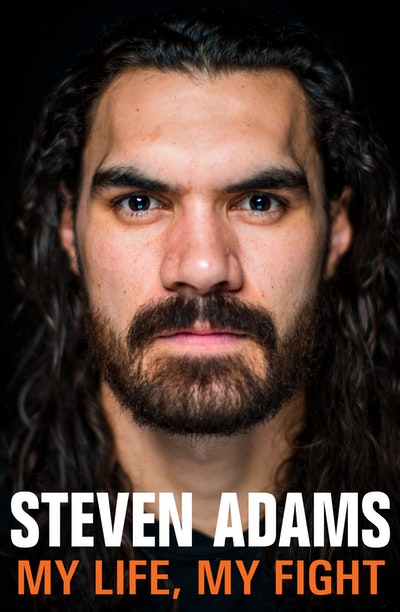

Steven Adams: My Life, My Fight Steven Adams

The previously untold story of Steven Adams' incredible rise to NBA stardom.

Buy now