- Published: 31 July 2017

- ISBN: 9780143770787

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $40.00

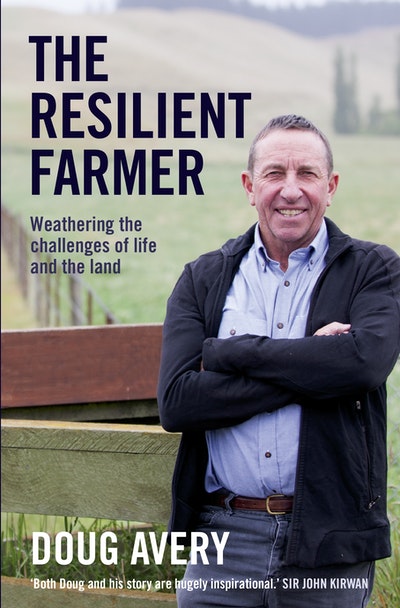

The Resilient Farmer

Extract

Eight years, the drought lasted. Then no sooner had we learned how to deal with that than nature sent us a wind that roared in like a high-speed train at 225 kilometres an hour, demolishing our fence lines and trees, our stoic stands of radiata pines, eucalypts and macrocarpas, as if they were skittles.

Even then she hadn’t done with us. Just weeks after the wind, in 2013, we were smashed by a magnitude 6.6 earthquake whose epicentre was only a couple of kilometres down the road. Our possessions were broken, and sooty bricks ricocheted through the rooms of our beloved home. In November 2016 we had a second earthquake that made the first seem like a pup – 7.8 magnitude. It terrorised our small rural community and deranged the land itself, lifting our entire farm, fortunately in one section, two metres higher and five metres north, brought hillsides crashing down, and tossed us all around as if we were nothing.

If we hadn’t realised it before, surely we know it now: we humans are like fleas on an elephant, just a minuscule part of the great, rolling processes of our planet. Droughts, wind, earthquakes . . . we can’t stop these things happening. Nor can we escape the usual ups and downs of life: our family, like yours, has had its trials, its cancer scares, its timely and untimely deaths. Governments make good and bad policies that help or hurt us; the global economy is a force that must always be reckoned with. For farming folk as for everybody else, the really big things in life are outside our control. The only thing we can control is how we meet these challenges.

The first five of those drought years, things got pretty ugly for me, and I dived into a very dark pit. No matter what I did, I was unsuccessful. I had a destroyed farm, a destroyed bank account and destroyed hopes. The feeling of failure struck at the very core of my being: I thrive on reward, and that had vanished from my life. I was so ashamed and afraid, and yet so determined to blame everyone – anything – else for my problems. I was that man who wouldn’t come to the phone, who pushed everyone away, who bristled with anger and impatience, and who drank himself to sleep every night. I was that man who did his best to make his own wife leave him so there’d be no one left to witness the shame. I came pretty close to being the man who gets to the end of his tether and just ends it all.

All that saved me was a bit of luck. Help came to find me, in the form of a young sales rep who was pushy enough to make me leave the farm for a day. I didn’t want to go, couldn’t see the use, but he turned up anyway and made me get in his car and go with him to a field day down in Waipara. And on that day I got handed some hope: hope in the form of a new idea, a solution to a problem I hadn’t yet understood. I thought my problem was drought; it wasn’t. My problem was the way I farmed, and the way I thought about things.

Even at my lowest point, I wanted to find a solution. I remember sitting with a neighbouring farmer, my friend Kev Loe, looking out at the hillsides, the way they were splitting open under the sun’s blowtorch, knowing we had no water for our animals, feeling disgusted and ashamed and gutted. He said to me: ‘There’s as much opportunity out there, Doug, as there’s ever been – it’s just, have we got the eyes to see it?’ I thought and thought about that. I wrote it down on a piece of paper and put it beside my computer. I used to stare at that bit of paper and think: ‘But what . . .? And how? How?’

Well, he was right about the opportunity, but I was never going to find the answer on my own. I wasn’t even asking the right question. ‘How?’ was not the place to start. I was still some years away from meeting the guy who would teach me the real question to ask.

Way back then, the new idea that rescued me and set me off on my process of discovery and change came in the form of a plant – a plant we’d been growing for eighty years, but hadn’t seen the potential of: lucerne, whose long tap root has the power to transform the way we utilise water. I’ve since been dubbed ‘the Lucerne Lunatic’ for my endless attempts to spread the word to other farmers. But, as a friend of mine said: ‘Doug, your story’s not really about lucerne, is it?’

‘No,’ I agreed. ‘It just happened to be our tool. This is a story about changing the way we integrate into the world.’

That new idea eventually led to me farm differently and over the years took me from failure to success, with a ton of help along the way. I went from zero income in 1998 to winning South Island Farmer of the Year in 2010. We’ve increased our land holdings and massively increased our outputs and our profitability, while being far more environmentally friendly. We are the same family with the same farms in the same valley in the same climate. The world hasn’t changed, but the story has changed. We turned our system on its head and we became a success story.

Learning to farm differently – to farm with nature, rather than against it – is at the heart of that success. But, even more important, I had to change my thinking processes. I became emotionally resilient. Now, I always put that first. I have no comprehension how people can run businesses of any kind if they’re not emotionally strong. In the last few years, my interest in life has turned to the management of my own head. My top paddock. Any of us, rural or urban, can do well, but only if we untangle the processes of our own minds.

I’m not a book-learned person. I learn from life, from my experiences, and most of all from those around me, and I’ve been lucky to meet some wonderful people. They probably all thought I was talking too much to take in anything they were saying, but I was listening. Sponge-learning – that’s what I do. My great motivating desire is not to be better than anyone else but to be better than I used to be. Self-improvement is at the core of this man.

My story is not just about agriculture. It’s about having life go badly wrong, but finding solutions that work. It’s about learning to pick the people who can help you create solutions, as opposed to those who can just further the damage.

We have been helped to find incredible success here at Bonavaree, and now my journey is around sharing the things that made a difference to me. Good people don’t stop and run off with the prize. They try to create and enhance the opportunity for a prize for somebody else.

The Resilient Farmer Doug Avery

The story of how one man weathered years of drought and desperation to turn his farm - and his life - around.

Buy now