- Published: 5 March 2024

- ISBN: 9781776950812

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $37.00

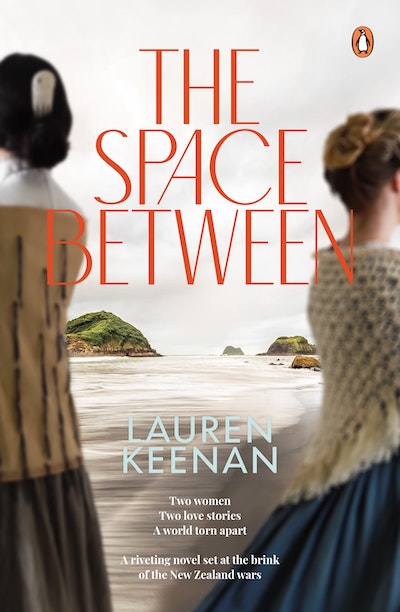

The Space Between

Extract

CHAPTER ONE

FRANCES

NEW PLYMOUTH, FEBRUARY 1860

Frances heard the commotion before she saw it: a man being arrested by two soldiers of the Crown, right in front of Thorpe’s General Store.

‘I belong here!’ the man shouted. ‘Nō Te Ātiawa au. This is our place.’ He wore a European shirt over trousers that were far too short. His black hair was unkempt, his eyes bright.

‘You need a pass to enter the township,’ one of the soldiers said, hands gripping his rifle. The soldier’s uniform was crisp and tidy: black trousers and a navy-blue tunic with shiny buttons. ‘Natives are not allowed here without swearing allegiance to the Queen. You should all know that by now. And you’re disturbing the peace by yelling.’

‘Go,’ the other soldier said. ‘Move.’

The man was led away, head bowed, past the staring customers at the butcher’s, the seamstress’s workshop and the bakery. Past the pile of cut wood that would soon be another military blockhouse, built to ensure that the likes of this loud, shabby man were kept out of the settlement. How unpleasant. Frances preferred not to think about what the newspapers called the ‘native troubles’ — it was alltoo frightening. So, she wouldn’t. She’d think about something else instead.

Frances turned towards the general store: a low, rectangular building made of roughly cut timber, with a small six-pane window so her view was not clear, which was no doubt why she mistook the man on the other side for Henry. All thoughts of the arrest flew from Frances’s mind. Henry? She thought. Is it you?

Of course it wasn’t him. Frances sighed. She couldn’t decide if she would rather Henry was dead or alive. She saw him far too often: outside the public house, mounted on a passing horse or strolling down the street. Each time she would turn towards the man, mouth dry. Oh, Henry, she’d think. Is it you? But then ‘Henry’ would transform into someone else with broader stature and darker colouring. Frances would be left with a dull ache in her stomach and a single thought swirling around her mind: What happened to him?

Moving to this remote backwater was supposed to make her visions of Henry go away — indeed, that hope had sustained her during the long, arduous voyage from England. But it hadn’t worked out that way, for she saw him just as often here in New Plymouth as she had in London. Last week he rode a horse through a paddock near her farm. Two days later he marched in formation with a garrison of soldiers, rifle pointed at the sky. Yesterday was worse than usual: Henry was a workman building the blockhouse; he was a drunken wastrel begging outside the hotel; he was yet another soldier — an officer this time, rather than one of the rank and file. He was everywhere. And here he was again, stepping out of Thorpe’s General Store, sack of flour in his arms.

He stepped around a muddy puddle, narrowly avoiding a pile of horse manure. This man had Henry’s agile footwork; Henry had been a fine dancer. Was it him? Frances knew it couldn’t be. Twelve years had passed: it was time to stop looking. And sure enough, this wasn’t Henry. This man was older and rather dishevelled, with no hat and tattered moleskin trousers, as well as a cloak of leaves, the sort one usually saw worn by Māori. Her Henry had never even seen a Māori, let alone donned their garments. Henry was a man of London, not the colonies.

The man with the flour stopped in front of the noticeboard, just as Frances herself had done before she’d heard the commotion. There were only two updates today: the mail coach was due on Monday afternoon; and a new public establishment had opened, offering rooms and stables. The man shook his head and turned away — he obviously found the news as dull as Frances had.

Stop staring, Frances! she admonished herself. It’s not Henry. No amount of unseemly gaping would change that fact. Frances scanned the street. It wasn’t long before her brother George would return with the cart, and she had several items on her shopping list: cloves, flour, carrots, lard, treacle. Candles, though George said they needed to make their own, and she had no idea how.

Once finished at the store, Frances would fetch some beef from the butcher, but only if it was fresh off the cow. Milking their own cow had caused her hands — mercifully hidden in her gloves — to grow thick and raw since they’d left London; they were stronger, but so much less ladylike. Nor were they improved by the dirt under her nails from tending the vegetable patch, or the network of scars from a particularly feisty hen that had taken exception to her eggs being collected. If only they had enough servants to do this work.

Henry was hard to forget. He had always been brimming with energy; not overburdened with riches, but a man with prospects. He was a valued assistant to a wealthy merchant who shipped all sorts of expensive goods up the Thames from the far reaches of the world.The merchant was an acquaintance of George’s, which was how Frances had met Henry, and then just when she thought nothing but happiness lay ahead for her, Henry had disappeared.

Mother had the bizarre notion that he must have ended up working on London’s docks and had likely perished there, as so many men did — especially, Mother said, those of Henry’s ilk. According to Mother, Henry might have been the son of a doctor, but that didn’t make him a gentleman. Or perhaps he had been caught in some nefarious dealings, Mother had mused, pointing out that Frances had never actually met Henry’s family, so who could attest to either their respectability or their solvency?

‘Stop being so self-indulgent,’ Mother initially complained. ‘Thinking too much is like walking around an object and poking it with sticks. Doing so does not change the object in question. All it does is weaken one’s sticks.’ She usually followed this with a litany of her own woes: ‘Do you think I wallow about all day, crying about my husband passing away? Or my darling Albert, gone too young? Such a charming, clever man he would have grown to be, had the fates not been so cruel.’ The litany was to get longer soon after, as the truth about Father emerged. ‘Thank the Lord,’ Mother then reiterated on a regular basis, ‘that George has found a way to restore our fortunes, even if it means we must travel so very far from home.’

Yes, they were lucky to have George, but over the years Frances had been unable to stop herself from constant imaginings of a life with Henry. What would it have been like? What had happened to him? She’d already lost Father and her other brother Albert, so the thought of Henry also being dead was too much to bear.

As was the thought of him being alive.

Had Henry died, he’d left this Earth wanting to marry her, which meant she hadn’t been abandoned by the only man she’d ever loved. But if he were alive, he’d dropped her, probably for a far superior and more beautiful heiress, not even caring enough to write. That opened too painful a chasm of speculation. If she knew Henry were dead, Frances would feel sad, bereft and melancholy. The idea of him being alive awakened much more uncomfortable feelings, such as anger, infused with regret. Not knowing meant she did not know what to feel.

Frances shook her head: she mustn’t wander down the dark and murky path of wishing Henry dead. Surely, Henry being alive but elsewhere was better? She was wicked for entertaining thoughts to the contrary. And yet, if Henry were alive, what did that make Frances — she who had mourned his loss for over a decade?

She shivered and pulled her shawl tightly around her shoulders. New Plymouth wasn’t cold like England, but there was a dampness that seeped into her skin and sat in her lungs, even in summer. It crept from the undergrowth of the dark forest that surrounded the township, bush that was filled with birds the size of small chickens. The trees stretched all the way from the recently cleared farmland to the large inland mountain. It was thick and impassable— claustrophobically so. And there was little in the drab wooden shops straggling along the muddy street to lift her spirits. What a pity the store didn’t stock vibrant fabrics or interesting ornaments to brighten her mood . . . what a pity she’d had to move here at all. A sound caught Frances’s attention: a cry, followed by a sharp inhalation of breath. The man with the flour had dropped the sack, which hit the ground with a thud. Frances turned to see him looking down at the flour and back up at her.

‘Frances?’ he said. ‘Is that you?’

Frances’s stomach lurched.

‘It is you!’ Henry went to lift his hat to her, but realised he did not have one. The Henry she once knew would never have ventured out bare headed. ‘Frances Farrington. What are you doing here?’

The Space Between Lauren Keenan

A gripping historical novel set amid the New Zealand Wars in 1860.

Buy now