- Published: 29 March 2022

- ISBN: 9780143776673

- Imprint: RHNZ Black Swan

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $37.00

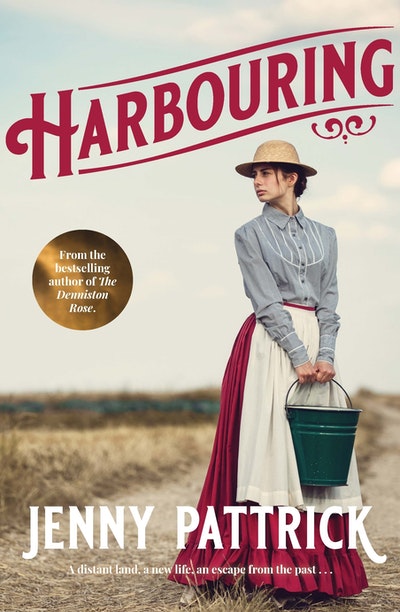

Harbouring

Extract

That set me wondering. The wife? Gareth in trouble again? Baby sick, or worse? Messages don’t come two a penny to the likes of a foundry worker. I scraped and swept with a will, in a fever to know. Whistle blew and I was up the steps to his office within the minute.I held no love or respect for the boss — an Englishman of course; he cared not a jot for his workers. We were dispensable ants to him. An accident or a death among us and he would shrug. Plenty more desperate for work out on the streets. I was careful to smile, mind —daren’t let my true feelings show. If I lost this hellish job, we might as well curl up our grimy toes and wait for death.

Boss handed me a piece of paper. ‘Message from some fancy feller. I told him he’d have to wait till shift end, and he went off in a huff. Tried to tell me it was urgent. Foundry work is urgent, I told him. You want to meet my worker? Do it in his own time, not mine.’

Just one more word from that fat slug and I would have crowned him, I swear. I snatched at the paper and ran off, clang, clang, my boots down the iron treads, outside into the grey light. What fancy feller? And where was he now?

The note was brief. Colonel Wakefield has a task for you. I am at the White Hart Inn, Tredegar Street, until six o’clock. — J. J. Small.

My shout set the pigeons on the clock tower flapping. Part pure joy and part anguish. Tredegar Street was in Pillgwenlly. It lacked only five minutes to the hour: I could not reach the hotel in time. Sure I could not. But would die in the attempt.

All my tiredness gone, I raced down over the cobbles, never mind the smog and black, belching chimneys, past the market, closed for the day, and headed for the river. Wait, wait, I prayed to Mr Small, whoever he might be. Stay another five minutes. The clock struck six, and I was still on wrong side of river. Take a last pint, mister, I am on my way. Over the River Usk I pounded, heart bursting,and into the area they call Pillgwenlly. Tredegar Street, yes, but which way? Right or left? ‘The White Hart!’ I shouted to a smart gentleman, who gave me a startled look and pointed. There it was in front of my very nose. Please God and all His Archangels the man had not left.

Inside the door I wasted no time. ‘Mr Small? Is there a Mr Small in the house?’

The bar was crowded. All heads turned towards me. I can make a decent cry when pressed, as the Colonel well knows. ‘Mr Small?’ What a picture I must have cut. These were commercial men in their tidy suits and ties. My face would have been black from the furnace,my hands grimed, shirt-sleeves dirty and no coat to cover them; not even a cap to my wild hair. No way to meet someone in the Colonel’s employ. I began to fear Mr Small, if still present, would turn on his heel at the sight of me. I drew a cloth from my trouser pocket and wiped my sweating face. ‘Mr Small? I am Huw Pengellin, the Colonel’s man!’

For a moment there was silence in the pub, and then a tall fellow close by rose, looked me up and down, nodded and drew me into a corner. He carried two pint pots with him and set one before me. I could have cried with joy; like as not I did.

He waited politely until my labouring breath steadied and my shaking hand was able to raise the pot. He watched me drink, not smiling, nor frowning either. A strange, quiet fellow. Surely he would be wondering why the Colonel wished to give me a task.

I tried a smile. ‘Forgive my appearance, Mr Small. As you will understand, I was in a fever to answer the Colonel’s call. I can scrub up quite respectable and pass for a regular fellow. Colonel Wakefield will vouch for that.’

Mr Small nodded thoughtfully and took a pull at his pint. ‘Colonel Wakefield tells me you are a good procurer.’

This startled me somewhat. I hoped this was not some illegal orindecent plan. The Colonel was no angel and loved a wild adventure.‘Procurer of what exactly?’ I asked cautiously.

Mr Small allowed a prim smile. ‘Of a variety of materials and goods for his men, I understand. He says you served under him in Spain and were always able to find his Lancers whatever was needed, even when the king’s army failed to provide.’

Our conversation continued without yet mentioning what ‘procurement’ the Colonel had in mind. I believe Mr Small was assessing my character. He asked about my reason for leaving the British Legion (lack of pay, a pregnant wife) and my present circumstances (pitiful, though I cast them in a slightly more rosy light, choosing not to describe our wretched manufactory hovel or my indebtedness).

Finally, he came to the point. ‘You have heard of the New Zealand Company?’

I had not.