- Published: 31 July 2017

- ISBN: 9781760141868

- Imprint: Penguin eBooks

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 320

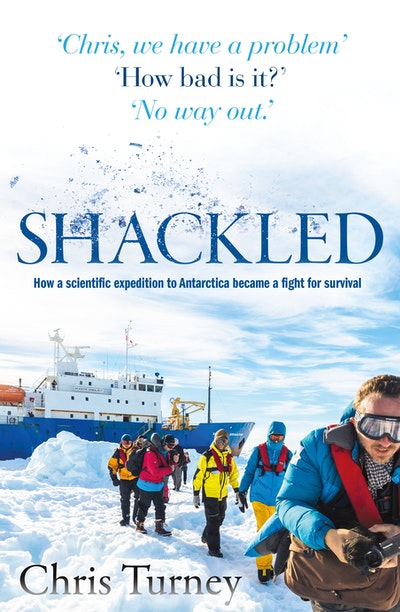

Shackled

Extract

Just thinking the words scares me.

I’m standing alone on a windswept deck looking out over the Antarctic coastline and the wildest landscape I have ever seen. We’re over 2700 kilometres from civilisation and things don’t look good.

Our ship, MV Akademik Shokalskiy, has spent the last four weeks fighting the stormiest seas on our planet. For four weeks I’ve shared our small vessel with seventy-one other souls, leading a scientific expedition to study this extreme environment. Arriving at the edge of the continent, we successfully crossed 65 kilometres of sea ice to reach a hundred-year-old wooden Antarctic base, a time capsule from the Edwardian age, to complete research the first polar scientists could only have dreamed of. With the science program nearly done, we took the Shokalskiy round to the east for one final piece of work. We finished yesterday and, flushed with success, were heading home.

Now we’re surrounded by ice . . . lots of ice.

I’m struggling to understand what’s happened. Just a few days ago we sailed these same waters, an area that satellite imagery showed was free of ice. We passed some patches forming on the freezing surface, but nothing to be concerned about. Now we’re hemmed in by slabs of ice, some measuring 3 metres thick, their immense size signifying they’ve formed over several winters. The amount of ice smacks of a catastrophic realignment up the coast, somewhere out to the east. Shattered by strong winds or broken up by rising temperatures, the ice has swept out to sea and into our path, too fast for us to dodge.

History is repeating itself. The expeditions of a century ago returned from the Antarctic with tales of adventure, tragedy, heroism . . . and sea ice. Sea ice was the villain of the south; the single greatest reason for lost lives and ships. No vessel was free of the risk, even at the height of summer. And no one experienced it worse than the great explorer Ernest Shackleton, who in 1915 lost his ship, the Endurance, to the crushing pressure of pack ice.

I search the horizon through my binoculars, looking for anything that might hint at a route to open water and freedom. The explorers of old like Shackleton learned that ominous dark skies promised open water reflecting on the clouds above, but the nearest ‘water sky’ is 4 to 7 kilometres away. It may as well be a hundred. My freezing breath condenses on the lenses. I rub them clear with my gloves and look again.

Nothing breaks. There’s ice as far as the eye can see.

I look at the weathervane overhead. It remains stubbornly fixed on the southeast, and the frenetic spinning of the wind cups shows no let-up on the 70 kilometres an hour we’ve had all day. Huge slabs of ice jostle for position around the ship. If only the wind would ease off, or better still, change direction, it might loosen the pack and give us a chance to get out of here.

In the frigid wind, I catch a distant laugh from below decks.

It’s Christmas Eve 2013. All over the boat, decorations have been put up. Flashing lights adorn the corridors, tinsel hangs around the dining room and banners flutter from the ceilings. We’ve even brought two green plastic Christmas trees, already sheltering a pile of presents for tomorrow. There’s concern aboard, but hopefully we’ll be moving again soon.

I lower my binoculars and turn to join the party below.

Six hours later, I wake and sense something is wrong. I lie still for a moment, wondering. Then I realise: the Shokalskiy’s quiet. The constant throb of our ship’s engines has stopped.

I scramble out of bed and throw on some clothes. This is bad. This is very, very bad.

I grab my down jacket and leap up the stairs to the ship’s bridge. It’s half past five in the morning and most of the expedition team are still in their cabins.

But up on the bridge there’s a frenzy of activity. Several Russian crew members, led by the captain, Igor Kiselev, are checking screens and poring over maps. His strained face says it all. It’s clear Igor has been up for hours. A native of Vladivostok, white-haired, stocky, and a polar veteran of over thirty years, he is normally bullish. Not this morning. A gruff ‘Morning’ in his strong Russian accent indicates all is not well.

‘Chris, we have problem.’

‘How bad is it?’

‘No way out.’ He sweeps his arm towards the windows and horizon beyond.

I look aghast at the scene before me. The ice has closed up even more. What little water was visible last night has disappeared, replaced by thick, tightly packed blocks of ice that slam into each other, thrusting chaotically into the air.

I look at the navigation monitor, and my stomach knots. The path of the Shokalskiy is plotting automatically on the screen. The rudder is blocked and with the engines turned off, our vessel has no steerage; the wind is pushing us, with the pack ice, towards the coast. The rocky outcrops lie just a few kilometres off the port side. It’s like a car crash in slow motion. Unless the wind changes or the ice packs in hard enough between us and the shore, there’s nothing we can do to avoid being thrown against the continent. The ship will be smashed to pieces, and we’ll have to evacuate everyone on board.

But even more alarmingly, two towering icebergs, each weighing some 70 000 tonnes, are moving at a great pace off the starboard side. The arrival of icebergs on the scene is a different threat altogether. In contrast to pack ice, which forms in the ocean, icebergs originate from the continent, shed by glaciers and ice sheets, and are far larger. They can extend hundreds of metres into the deep, where they’re steered by ocean currents. There they can pick up speeds of two to three knots, ripping through ordinary sea ice and anything else in their path, often in a completely different direction to the prevailing wind. If these icebergs set a trajectory for our 2100-tonne ship, they could be upon us within a couple of hours. There won’t be much time for an evacuation; we’ll barely have time to get everyone off the stricken vessel before it’s crushed to pieces.

And then Igor gives me the bad news: a tower of ice has pierced the ship during the night, ripping a 1-metre hole in the hull, threatening one of the water ballast tanks. The destruction of the Shokalskiy has already begun.

I stifle rising panic as Igor pulls out the latest weather charts and spreads them on the table. The tightly packed pressure bars and thick arrows all point to an approaching blizzard and persistent winds from the southeast.

Igor flicks over the page to recent forecasts for the next few days. ‘No relief.’

I reel at the news. We have to get help, and we have to get it fast. I stagger back towards my cabin, numb. This can’t be happening.

The trials of past endeavours conjure up the worst possible scenarios in my mind. Shackleton and his men were stuck in the ice for two years. A thousand kilometres from civilisation, they faced isolation, starvation, freezing temperatures, gangrene, wandering icebergs and the threat of cannibalism. But by sheer positive attitude and superb leadership, the Anglo-Irishman kept his team together and returned everyone home. No matter how bad conditions became, Shackleton never lost a single life.

But there’s a difference between him and me, I think, as I open the door to my cabin and see my wife Annette, fifteen-year-old daughter Cara and twelve-year-old son Robert sitting at the table, smiling and laughing, waiting to open their Christmas presents.

Shackleton didn’t have his family with him.

Shackled Chris Turney

When Australian-based scientist Chris Turney’s expedition got stuck in the Antarctic ice in 2013, it brought global attention to the dangers of the world’s least-known continent – and its fragility. Turney tells his own dramatic tale against the backdrop of the compelling history of Antarctic exploration and inspired by fears for the continent’s future.

Buy now