- Published: 31 July 2017

- ISBN: 9781925324990

- Imprint: Ebury Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $40.00

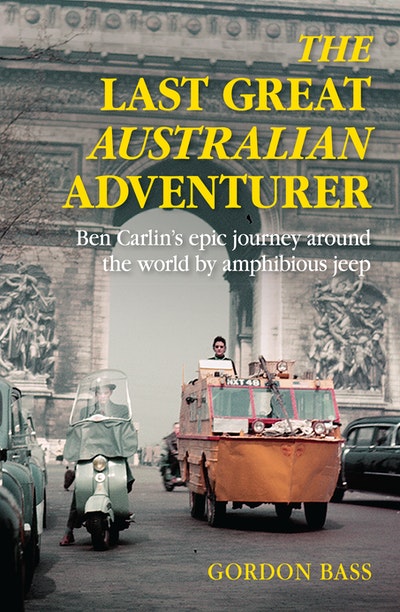

The Last Great Australian Adventurer

Ben Carlin's epic journey around the world by amphibious Jeep.

Extract

26 June 1957. A small Japanese fishing trawler from the port of Hakodate rolls over dark swells on the North Pacific, treading Russian waters to the south-east of the Kamchatka Peninsula. A cold wind slices in from the north-east, whipping salt spray across the deck. Under the slate predawn sky, oilskin-clad fishermen winch a driftnet up from the sea, its nylon web taut with the weight of salmon.

A bright flash of yellow a hundred yards away catches the eye of a leathered fisherman. He turns to squint into the distance. He sees it again. It’s an improbable speck riding low in the water, a tiny boat of some sort, no bigger than a car, looking almost like a drifting shipping crate. A stumpy mast juts from its boxy cabin, flying a traditional Japanese carp flag that’s torn and blackened by exhaust.

As the vessel crests each wave, the fisherman sees something even stranger: it has wheels.

Now a hatch flips open on the boat’s roof and, as the fisherman watches, a man pulls himself out. He appears solid and powerful. He has a full grey beard and a large knife clenched in his teeth.

He is naked.

It’s as if Ernest Hemingway himself has materialised in the vastness of the North Pacific, barrel-chested and strong, a strange sight indeed.

The fisherman motions for the rest of the crew to join him. Together they watch as across the waves the bearded man stands on top of his small boat in the sharp wind, pauses and dives into the 4-degree Celsius water.

The two vessels drift closer, until they are just 50 yards apart. Now the crew sees the madman break the surface to fill his lungs. In the icy water his body is the colour of pale marble; in survival mode, it has shunted its warm blood inward to vital organs.

The fishermen see a second man, thinner and much younger, a wool cap pulled low against the cold, emerge from the hatch of the odd vessel. He doesn’t try to help the bearded man, but instead aims a camera at him and starts taking pictures, as if it’s all he can do.

The bearded man clings to the side of the strange yellow boat for a moment, gasping for breath. Then he inhales deeply and plunges back below the surface.

On the trawler, Captain Amiya Daiichi joins his crew, watching in vain for the man to reappear. He knows now what has happened: the strange boat has snared itself on the submerged skein of his trawler’s huge driftnet, which is suspended from a series of floats and stretches for more than a mile across the Pacific. And instead of asking for help, the boat’s pilot is in the water, trying to hack through the netting to free his odd vessel.

It’s madness. Suicidal.

Two minutes pass, then five. Captain Daiichi knows from experience that the man’s core body temperature is plummetting. Once it reaches 32 degrees he will lapse into semi-consciousness, and at 26 degrees he will experience cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. Without protective gear, death will come in minutes. Perhaps he’s already dead.

The boat bobs alone in the ocean.

And then –

Sliding over the trawler’s gunwale, tangled up in netting with tons of salmon, the bearded man reappears. He’s been caught in the trawler’s driftnet, hauled up with the teeming catch, and now he collapses onto the gore-slick deck and gasps for air. Stunned, the fishermen pull him free of the net and hustle him into their smoky galley, where they prop him in front of a coal-burning stove, wrap him in a fur coat and force hot sake down his throat to speed his sluggish heartbeat.

As his body warms up, the man turns lucid, then belligerent. In fragments of Japanese he asks for a knife to cut their lines from his propeller. He insists on returning to his vessel. He tears off the coat and storms out of the galley into the cold grey morning, pausing at the gunwale before diving back into the ocean.

He tells the fishermen that he is driving around the world.

Back in the driver’s seat of his small yellow vessel, the bearded man pressed a starter button with his foot, glanced at the compass and pushed in the throttle.

His co-pilot knew better than to say anything.

Ben Carlin, 44 years old, son of Western Australia, veteran of the goldfields, former major in the Indian Army, was two weeks out of northern Japan, rumbling across the North Pacific towards Alaska on his way to Montreal, where he’d begun his journey in 1950. He was seven years into one of the great adventures of the twentieth century. Nine if you counted the two years of false starts.

He was circling the world in a surplus World War II Ford GPA amphibious army jeep called Half-Safe.

It was an audacious, death-defying adventure, unlike anything attempted before. And it had once brought the rugged Australian adventurer a measure of fame and notoriety. In the early 1950s he had appeared on radio and TV after an astonishing, near-fatal Atlantic crossing. He had mingled with royalty and celebrities. He had written a highly anticipated book about the gruelling first stage of the journey. He had been praised by Life magazine, profiled by the BBC, splashed across the front pages of newspapers in Australia and around the world.

But then things had taken a puzzling turn. Before he was even halfway around the world friends and lovers began abandoning him, the media turned their attention elsewhere, his book failed to sell, and his fame began to ebb. By 1957 the journey was mostly regarded as a pointless stunt, to the extent that anyone thought about it at all. And by the time I found an inscribed copy of Ben’s book on my parents’ bookshelf, twenty-five years after his death, he was little more than an occasional, obscure footnote in the annals of adventuring.

I was fascinated. Why had Ben Carlin’s circumnavigation taken so long, and what made him press on year after year, long after the world lost interest? What had he done next? Why had he been forgotten? Who was he? The answers, I would eventually find, were evasive and complex. They had to be teased out of the arc of his life.

There was one early clue.

Norman Lindsay, the great Australian writer and artist, spent the better part of his career obsessed with issues of spirit and adventure. He followed Ben’s voyage through the years with keen interest, and he saw an extraordinary quality in the man and his quest.

In 1956, Lindsay wrote to Ben from his home in the Blue Mountains to voice admiration and to explain why he believed the amphibious journey had a profound meaning.

As far as collective action goes, Australians have done that splendidly in two world wars, but unless the individual can express the spirit that drives the mass, its moral value is more or less lost. I’m really not making any sort of overstatement when I say that I prize your Half-Safe voyage as I prize a fi ne poem or a picture produced by an Australian. Blood and spirit are inseparable, and I’ve damned my own destiny sufficiently for anchoring me by the backside in a studio all my life to define as best I can what spirit means to me, while those who have its blood also can go recklessly around the Earth’s crust and do all sorts of admirable things and, if they have the wit, make a book out of them, so that poor devils incarcerated in shadows can share them second-hand.

Lindsay understood Ben. He believed he was pursuing something that would elevate him to the pantheon of Australian adventurers like Charles Kingsford Smith and Douglas Mawson, men who could be seen as the last of their generation, the last to press into the unknown with simple machines and minimal safety nets, men who ventured forth without satellite navigation and corporate sponsorships and civilisation just a phone call away.

He saw in Ben Carlin the embodiment of blood and spirit, the manifestation of drive and half-understood obsession. He saw free will.

Lindsay knew that most of us live with dreams unfulfilled and desires out of reach. We remain poor devils in shadows.

But Ben Carlin refused to live in the shadows. Even now, nothing would stop him.

He gripped the tiller of his battered amphibious jeep and steered eastward across the icy, rolling expanse of the North Pacific.

The Last Great Australian Adventurer Gordon Bass

The extraordinary adventure story of Ben Carlin, who circled the world, over land and sea, in his rusting amphibious jeep.

Buy now